Repetitive Unease: Zhang Peili at Red Brick Art Museum

When I decided recently to see Zhang Peili’s current exhibition “ZHANG Peili” at Red Brick Art Museum, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. I love art, and I enjoy going to museums and galleries, but my interest usually gravitates towards works of “traditional” media like painting, drawing, and sculpture. I’ve never really “gotten” the more conceptual branches of art – a few items scattered about in a room here, a toilet there… Honestly, I suppose I’ve judged such pieces as unserious and a bit full of themselves. Pretentious, if you will. That judgment has certainly prevented me from giving such art much of a chance. But for whatever reason, I decided to step out of my comfort zone and see if I could find something in this current offering at Red Brick to understand and appreciate or at least figure out “what the big deal” is. Having gone and actually allowed myself to experience this work, I am extremely happy that I did. This exhibition has changed my view of conceptual art and my relationship with it. The Artist Born in 1957 in Hangzhou, Zhang Peili has long been at the forefront of contemporary Chinese art. Over a career spanning more than 40 years, he has established himself as a pioneer in video art and is widely considered the first to explore the art form in China. His work deals mainly with the theme of repetition, with correlating themes of redundancy, recursion, grids, boredom, the mundane, and the experience of time. Zhang Peili’s exhibition at Red Brick Art Museum is a showing of his recent work with these themes and contains video art, object installations and kinetic installations. The Work In this solo exhibition, his largest to date, Zhang Peili continues his exploration of repetition by building on the concept of the grid as a structuring principle. Here the grid is not just a visual, static object; it is also expressed sonically as well as temporarily, physically, and emotionally. The grid is the connections between people, the organizing space around them, interactions and reactions between individuals, and the accumulation and repetition of individual events. The exhibition begins with Constant Rotation, which has been installed in the museum’s first-floor sunken circular space. In this piece, as the main structure begins to spin, the many propane tanks within are spun around forcefully. At certain intervals, a large magnet descends from the ceiling, picks up some tanks, and then drops them into the center of the spinning structure. When the spinning stops, the distribution of the propane tanks, affected by the forces imparted by the spinning motion, reveals a structure of its own. As we move through the exhibition, it becomes clear that lighting and positioning imbue “unremarkable” objects such as semiconductor radios, propane tanks and impressive machinery with the semblance of life and turns them into players in their scenes – entities in their own right. Many of the works use various approaches to re-contextualize the “function” of the component objects and invite the audience to make their own connections, associations and re-associations. Some works, such as Gentle Touch, create a sense of anticipation through direction or pattern of movement or sound and then subvert our expectations of the nature of interactions between objects and the effects of those interactions. As one progresses through the exhibition, it becomes apparent that sonic “interference” of different works creates a defined soundscape and contributes to building a particular world within which the individual works exist. It doesn’t seem too farfetched to say that the works, especially with the impression of “life” imparted by lighting and positioning, seem to inhabit the exhibition. Sound also plays an important role in the building of the grid in certain works. In Divisible Propane Tank I and Divisible Propane Tank II, in each work the two halves of a propane tank are mechanically separated and brought back together, the sounds of the propane tank halves separating and meeting again to form a temporary whole underline the end of one period of separation and the beginning of the next. Additionally, the occasionally almost musical sound of the machinery as it repeats its performances creates anticipation and structures the audience’s experience. In Word Press Machine, plates of Chinese phrases rotate and lower very slowly to create impressions onto a smooth bed of fine white sand. The phrases are just visible for a short period of time before the machinery, with its sonic qualities that create anticipation and release, disturbs and smooths the sand. The plates of phrases rotate again, and eventually, a new phrase is printed. Zhang Peili is also interested in time – in the experience of it and its effect. On the one hand, many of the exhibits, such as Dragging Mode, utilize mechanized elements moving at extremely slow speeds for elongated time spans that verge on the boring – another recurring fascination o

When I decided recently to see Zhang Peili’s current exhibition “ZHANG Peili” at Red Brick Art Museum, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. I love art, and I enjoy going to museums and galleries, but my interest usually gravitates towards works of “traditional” media like painting, drawing, and sculpture. I’ve never really “gotten” the more conceptual branches of art – a few items scattered about in a room here, a toilet there… Honestly, I suppose I’ve judged such pieces as unserious and a bit full of themselves. Pretentious, if you will. That judgment has certainly prevented me from giving such art much of a chance. But for whatever reason, I decided to step out of my comfort zone and see if I could find something in this current offering at Red Brick to understand and appreciate or at least figure out “what the big deal” is. Having gone and actually allowed myself to experience this work, I am extremely happy that I did. This exhibition has changed my view of conceptual art and my relationship with it.

The Artist

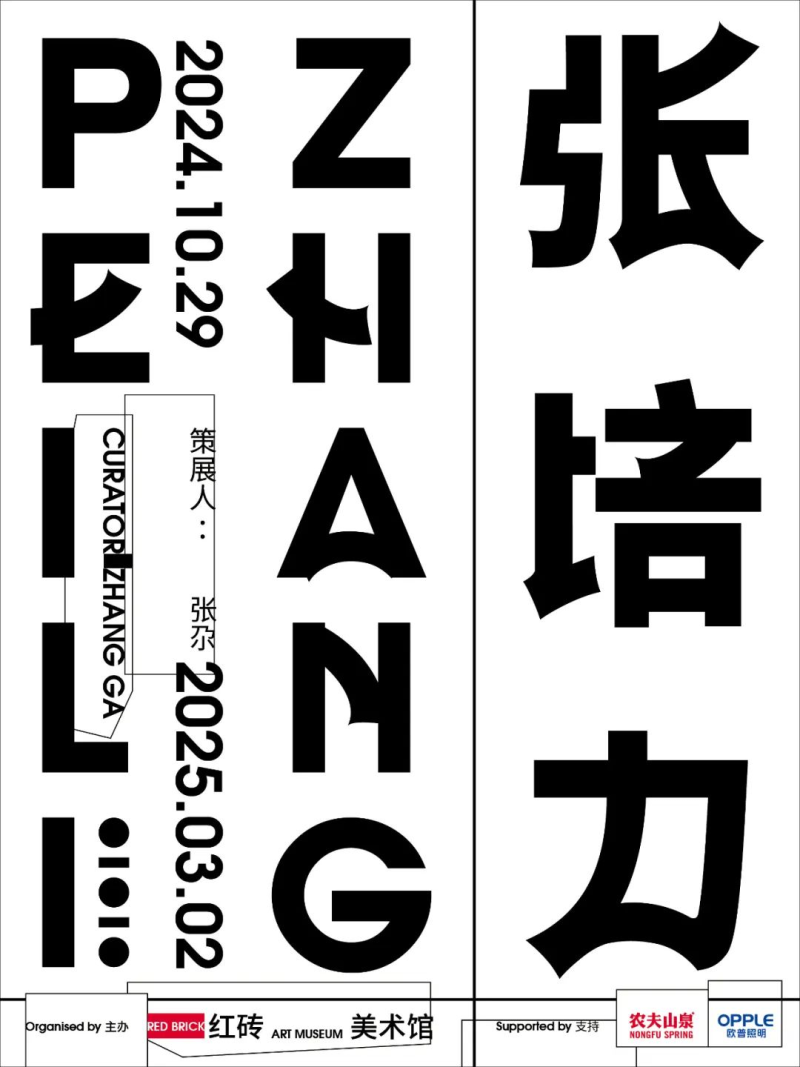

Born in 1957 in Hangzhou, Zhang Peili has long been at the forefront of contemporary Chinese art. Over a career spanning more than 40 years, he has established himself as a pioneer in video art and is widely considered the first to explore the art form in China. His work deals mainly with the theme of repetition, with correlating themes of redundancy, recursion, grids, boredom, the mundane, and the experience of time. Zhang Peili’s exhibition at Red Brick Art Museum is a showing of his recent work with these themes and contains video art, object installations and kinetic installations.

The Work

In this solo exhibition, his largest to date, Zhang Peili continues his exploration of repetition by building on the concept of the grid as a structuring principle. Here the grid is not just a visual, static object; it is also expressed sonically as well as temporarily, physically, and emotionally. The grid is the connections between people, the organizing space around them, interactions and reactions between individuals, and the accumulation and repetition of individual events.

The exhibition begins with Constant Rotation, which has been installed in the museum’s first-floor sunken circular space. In this piece, as the main structure begins to spin, the many propane tanks within are spun around forcefully. At certain intervals, a large magnet descends from the ceiling, picks up some tanks, and then drops them into the center of the spinning structure. When the spinning stops, the distribution of the propane tanks, affected by the forces imparted by the spinning motion, reveals a structure of its own.

As we move through the exhibition, it becomes clear that lighting and positioning imbue “unremarkable” objects such as semiconductor radios, propane tanks and impressive machinery with the semblance of life and turns them into players in their scenes – entities in their own right. Many of the works use various approaches to re-contextualize the “function” of the component objects and invite the audience to make their own connections, associations and re-associations. Some works, such as Gentle Touch, create a sense of anticipation through direction or pattern of movement or sound and then subvert our expectations of the nature of interactions between objects and the effects of those interactions.

As one progresses through the exhibition, it becomes apparent that sonic “interference” of different works creates a defined soundscape and contributes to building a particular world within which the individual works exist. It doesn’t seem too farfetched to say that the works, especially with the impression of “life” imparted by lighting and positioning, seem to inhabit the exhibition.

![]()

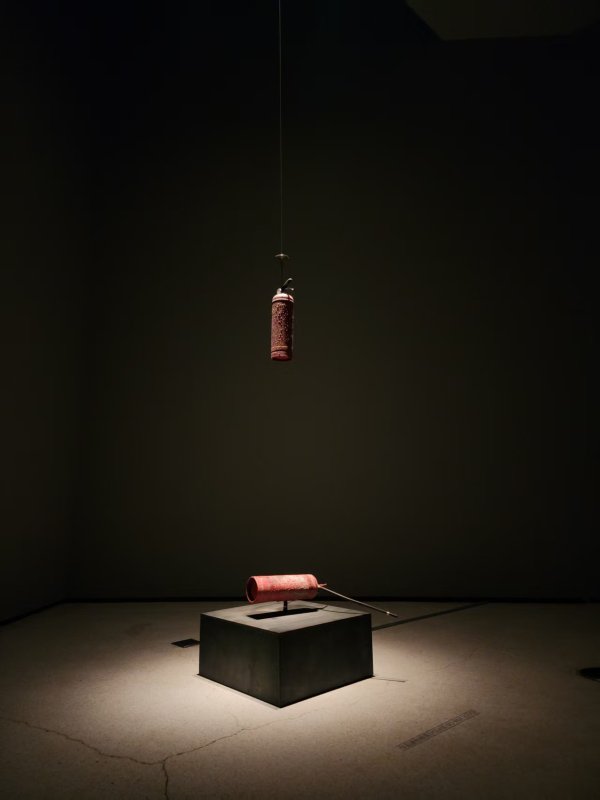

Sound also plays an important role in the building of the grid in certain works. In Divisible Propane Tank I and Divisible Propane Tank II, in each work the two halves of a propane tank are mechanically separated and brought back together, the sounds of the propane tank halves separating and meeting again to form a temporary whole underline the end of one period of separation and the beginning of the next. Additionally, the occasionally almost musical sound of the machinery as it repeats its performances creates anticipation and structures the audience’s experience. In Word Press Machine, plates of Chinese phrases rotate and lower very slowly to create impressions onto a smooth bed of fine white sand. The phrases are just visible for a short period of time before the machinery, with its sonic qualities that create anticipation and release, disturbs and smooths the sand. The plates of phrases rotate again, and eventually, a new phrase is printed.

Zhang Peili is also interested in time – in the experience of it and its effect. On the one hand, many of the exhibits, such as Dragging Mode, utilize mechanized elements moving at extremely slow speeds for elongated time spans that verge on the boring – another recurring fascination of the artist – and invite the audience to contemplate their experience of time itself. The elements themselves create a grid that structures and contains time, the space between events transforming into the content of the piece.

On the other hand, whereas the repetition of elements or events can accumulate meaning over time, with the whole process acquiring a particular overarching significance, some works take the opposite approach. One Word Per Minute, for example, deconstructs a phrase into its individual words, inviting contemplation of each separate character on its own terms within the space of anticipation of the next character or reflection upon the previous one. And with so many of the installations being kinetic and involving machinery performing repetitive movements, the effect of time upon the works over the period of the exhibition also has a hand in shaping the audience’s experience of the work.

But it’s not all cold mechanics. There is an emotional resonance to Zhang Peili’s work, as well – our interactions with the conceptual grid and our “bumping up against it” are rendered through our sensory experience and our perception. In Portrait of 2024, for example, a video of individual human faces is projected onto a large, ceiling-high screen for a bit of time each. Each towering face makes small movements with its eyes and mouth – the expressions inscrutable – then disappears from the screen as a countdown plays before another face appears. The emotional state of the subjects in the video draws us in, fueling our desire to know more about them. The loud, sudden and striking sound at the beginning of each video clip outlines clear sonic boundaries, the meeting and distancing from which elicit heightened emotion and a very clear adrenaline response.

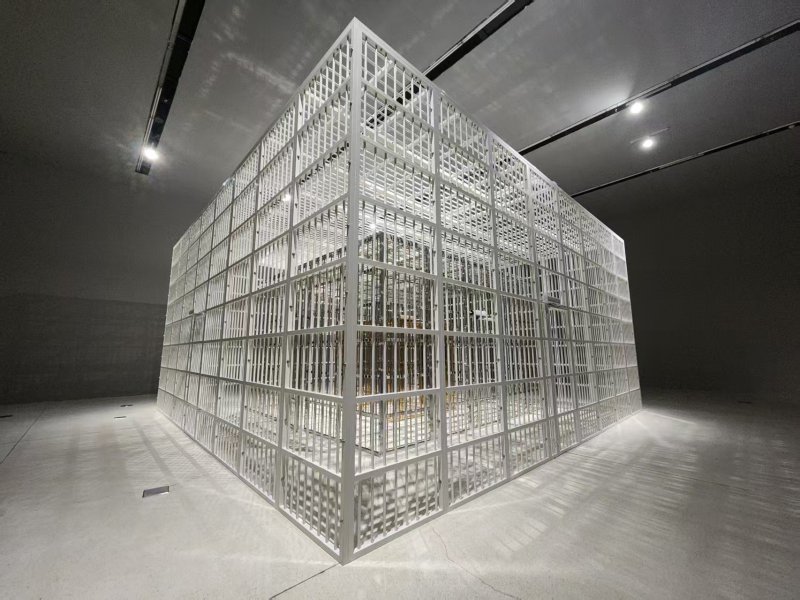

In Three Chambers, the audience is invited to a willing integration with a quite literal grid – a set of concentric cages with doors on each that open at different intervals enabling the audience to enter. This creates not only a relationship between those inside and those outside of the cages but also a relationship between oneself as one experiences being outside the grid and oneself as one experiences being “trapped” within each layer of it. The content of the piece becomes not the structure itself but the emotional experience of the people inside navigating their interaction with the structure.

Tension and contrast between position and perspective is also directly examined in The Last Few Minutes of a Life, a quietly poignant piece that employs macro-videography across a series of five coordinated video displays in a contiguous horizontal arrangement to confront the coexistence of different scales of existence and how and to what degree we assign value to different kinds of life.

Our thoughts create the grid as well, erecting and maintaining it in this situation through our experience of the exhibition. The grid is established by the gallery text and the artist as the framing conceit for the exhibition, so the artist has delimited and focused our perception and experience before we even begin. We are simultaneously limited in our perception and freed from a limited perception of the objects, time, place, and ordinary thoughts, which allows us to see the connections between them and the relation to our own lives. But as much Zhang’s work frees us from the traditional static notions of a grid, it is through this freedom that we realize the grid’s rigidity and omnipresence, raising a question: As we move through human experience, what connection does the grid have with our lives?

Perhaps the short film At Sea takes a stab at this question. In the film, a man floats in a life ring while performing everyday tasks such as making phone calls, brushing his teeth, taking selfies or eating a banana, seemingly oblivious to the movement of the ocean waves, which bob him about. The scene is in black and white, and we hear the sounds of waves which sound stormier than they appear on screen. At intervals, the camera pans up to above the clouds as the image is filled with color. The view above the clouds is quiet, and wondrously vibrant. Then we return down through the clouds to the stormy sounds and black and white color and the man floating in the sea who is engaging in another mundane task.

Life, then, as a kind of repetition, emerges in the form of a grid, ultimately an embodiment of the grid as structure, as an expression of pattern and path. Free, yet defined – the routines, habits, social encounters, experiences and expectations that emerge to form a larger, cumulative whole, and which we learn to accept and live within.

Visiting the Exhibition

Make no mistake – this is contemporary, conceptual art. Be aware of this and accept it before visiting. But if you do make the decision to see this exhibition, and if you keep an open mind, then you will be rewarded with a challenge and the chance to see and engage with the work of an incredibly important avant-garde and thought-provoking contemporary Chinese artist. And if this would be a new experience for you, it might even just ignite your interest in contemporary art, which we in Beijing are fortunate to have ample opportunities to experience.

It took me just under three hours to make my way through the entire exhibit, but I do take my time at museums. I believe a reasonable time estimate for completion would be anywhere from 45 minutes to two hours, depending on whether you rush through or take the time to contemplate. If you don’t live close by and would like to make a day of your visit, there are a number of shops, restaurants and other attractions at nearby Lotus Park and the 王府井奥莱·香江小镇 Outlets Town.

The “ZHANG Peili” exhibition is taking place at Red Brick Art Museum until Mar 2, tickets are RMB 120 and can be bought via the museum's WeChat mini program (search 红砖美术馆), or via this link.

Red Brick Art Museum 红砖美术馆

Hegezhuang Village, Cuigezhuang Xiang, Chaoyang District (on the northwest side of the intersection of Shunbai Lu and Maquanying Xilu)

市朝阳区崔各庄乡何各庄村(顺白路与马泉营西路交叉口西北侧)

Hours: Tue-Sun, 10am-5.30pm (closed Mon)

Phone: 010 8457 6669 ext. 8800

READ: Three Things for the Week Ahead in Beijing (Feb 17-23)

Images: Abigail Weathers, Wikipedia, Red Brick Art Museum