Original ‘Saturday Night Live’ Star Garrett Morris Talks About Marching in the ‘60s, Racism at ‘SNL’, Richard Pryor, and Why Sun Ra is Better Tha...

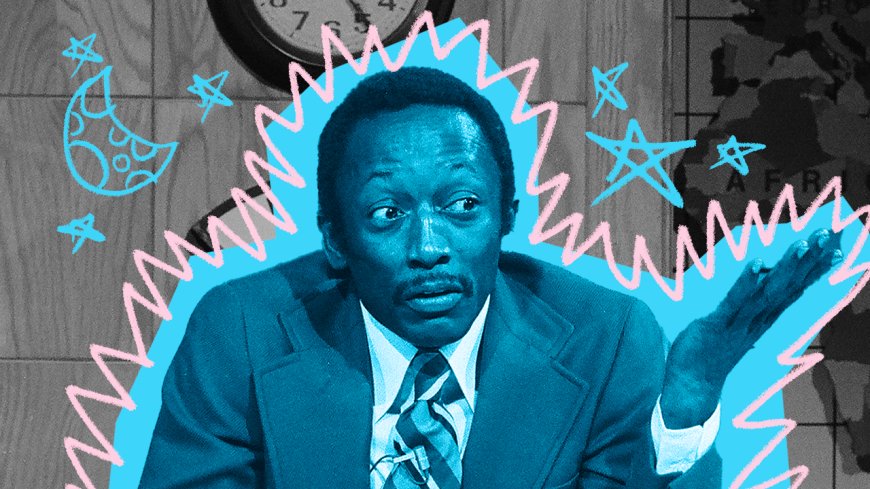

CultureMorris, now 87, struggled with stereotypical writing, personal demons, and the pressures that came with being SNL’s first Black cast member. “I got a letter from the NAACP,” he recalls, “telling me to straighten up and fly right.”By Alex PappademasJanuary 27, 2025Chris Panicker; Getty ImagesSave this storySaveSave this storySaveGarrett Morris was a 37-year-old Julliard-trained actor and playwright when he joined the inaugural cast of Saturday Night Live in 1975. His notable characters included fictional retired ballplayer Chico Escuella (author of the tell-all book Bad Stuff ‘Bout the Mets), the president of the New York School for the Hard of Hearing (who shouted Weekend Update headlines as Chevy Chase delivered them), various Nerds and Coneheads, and Black public figures from Louis Armstrong to Bob Marley to Idi Amin. Although he struggled with addiction during and after his time on SNL, he went on to appear in films like Car Wash and the cult classic The Stuff, and on TV shows like The Jeffersons, Hill Street Blues, Martin and Two Broke Girls. He’s been clean for many years, and received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2024. This interview was conducted at the end of last year, as part of the reporting process for the GQ feature “Saturday Night Forever.”GQ: Tell me a little bit about what you were doing before you got cast on SNL. What were you doing professionally? What was your life like?Garrett Morris: I started off as a singer. With a guy named Harry Belafonte. I don't know if you know who that is.Of course.I was with him for nine years. Meanwhile, I was also in some repertory groups. I was in a group called the Black Arts Theater. It was handled by a playwright whose then was called Leroi Jones. Later on he became Imamu Amiri Baraka. I was in that repertory group. Then I did Off-Broadway and Broadway. By the time Saturday Night Live got me, I had been on Broadway three or four times—with a musical, Show Boat, and Porgy & Bess, and later on with a thing by Melvin Van Peebles called Ain't Supposed to Die a Natural Death.I also taught high school on the Lower East Side. I taught at a maximum security prison, Great Meadows Correctional Facility, better known as Comstock. I taught at a juvenile facility called Cocksackie. I created the music department for a group called Mobilization for Youth on the Lower East Side.I wrote a play called The Secret Place, which was produced at Ellen Stewart's LaMama Experimental Theatre Club, among other places. Let's see. Damn—I had done some movies. Cooley High.I was part of a group of about 100 people who, from the early '60s till the end of the '60s, lobbied and marched to get Actors Equity, SAG, and AFTRA to change the way they dealt with membership. Because in the '50s and the early '60s, you had maybe 1% that was non-white, period. Including Latino [and] Black [members] it was about 1% or 2%. By the time we got through, Actors' Equity had elected its first Black president, a guy named Frederick O'Neal, and SAG and AFTRA had opened up their membership. I became a member in 1968. It wasn't just me. Raul Julia, Valerie Harper, as well as Bill Duke and Dick Williams. It was about 50, 75, 100 of us. We made a lot of enemies, made a lot of friends, and we caused some changes.And you were originally hired at SNL as a writer?Yes, I was. I'd written the play I told you about, The Secret Place. During the '50s and '60s, the groups that got together like SNCC and CORE—you know who those groups were?Yeah.SNCC, CORE, the Black Panthers. What happened was when black cops started being hired on police departments, one of the reasons why they were hired was to infiltrate those groups. And when one guy infiltrated the Black Panthers, somebody made him, and he had to escape and run for his life. He was living all over the country. And I remember thinking, What is that guy going through? Because at this time, if you're a Black man who's about 30, 35, the problems these groups were aiming at were real, no matter how flawed their approach was.So I wondered—a Black man who went through segregation in this country, who's now a cop, what is he going through? And my idea was he was probably having a lot of bad dreams. So I wrote a play called The Secret Place, in which a black cop infiltrates a revolutionary group. And he finally gets made. And in it, you couldn't just be serious, I had a couple of jokes. And when Lorne [Michaels] read it, he called me and said, "I want you to be a writer."To make it very short, I had a lot of problems writing [sketches that were] 15 seconds, 30 seconds, a minute. Because a play, you can write two hours. And that's what I was accustomed to. And I didn't get it together until I realized that in my play, I did have a joke about white liberalism, and how you had a group fundraising that was all Black, [you'd raise] a certain amount of money. But if you had some white people in there, in the '50s and '60s, you got a whole lot of more money, bec

Garrett Morris was a 37-year-old Julliard-trained actor and playwright when he joined the inaugural cast of Saturday Night Live in 1975. His notable characters included fictional retired ballplayer Chico Escuella (author of the tell-all book Bad Stuff ‘Bout the Mets), the president of the New York School for the Hard of Hearing (who shouted Weekend Update headlines as Chevy Chase delivered them), various Nerds and Coneheads, and Black public figures from Louis Armstrong to Bob Marley to Idi Amin. Although he struggled with addiction during and after his time on SNL, he went on to appear in films like Car Wash and the cult classic The Stuff, and on TV shows like The Jeffersons, Hill Street Blues, Martin and Two Broke Girls. He’s been clean for many years, and received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2024. This interview was conducted at the end of last year, as part of the reporting process for the GQ feature “Saturday Night Forever.”

GQ: Tell me a little bit about what you were doing before you got cast on SNL. What were you doing professionally? What was your life like?

Garrett Morris: I started off as a singer. With a guy named Harry Belafonte. I don't know if you know who that is.

Of course.

I was with him for nine years. Meanwhile, I was also in some repertory groups. I was in a group called the Black Arts Theater. It was handled by a playwright whose then was called Leroi Jones. Later on he became Imamu Amiri Baraka. I was in that repertory group. Then I did Off-Broadway and Broadway. By the time Saturday Night Live got me, I had been on Broadway three or four times—with a musical, Show Boat, and Porgy & Bess, and later on with a thing by Melvin Van Peebles called Ain't Supposed to Die a Natural Death.

I also taught high school on the Lower East Side. I taught at a maximum security prison, Great Meadows Correctional Facility, better known as Comstock. I taught at a juvenile facility called Cocksackie. I created the music department for a group called Mobilization for Youth on the Lower East Side.

I wrote a play called The Secret Place, which was produced at Ellen Stewart's LaMama Experimental Theatre Club, among other places. Let's see. Damn—I had done some movies. Cooley High.

I was part of a group of about 100 people who, from the early '60s till the end of the '60s, lobbied and marched to get Actors Equity, SAG, and AFTRA to change the way they dealt with membership. Because in the '50s and the early '60s, you had maybe 1% that was non-white, period. Including Latino [and] Black [members] it was about 1% or 2%. By the time we got through, Actors' Equity had elected its first Black president, a guy named Frederick O'Neal, and SAG and AFTRA had opened up their membership. I became a member in 1968. It wasn't just me. Raul Julia, Valerie Harper, as well as Bill Duke and Dick Williams. It was about 50, 75, 100 of us. We made a lot of enemies, made a lot of friends, and we caused some changes.

And you were originally hired at SNL as a writer?

Yes, I was. I'd written the play I told you about, The Secret Place. During the '50s and '60s, the groups that got together like SNCC and CORE—you know who those groups were?

Yeah.

SNCC, CORE, the Black Panthers. What happened was when black cops started being hired on police departments, one of the reasons why they were hired was to infiltrate those groups. And when one guy infiltrated the Black Panthers, somebody made him, and he had to escape and run for his life. He was living all over the country. And I remember thinking, What is that guy going through? Because at this time, if you're a Black man who's about 30, 35, the problems these groups were aiming at were real, no matter how flawed their approach was.

So I wondered—a Black man who went through segregation in this country, who's now a cop, what is he going through? And my idea was he was probably having a lot of bad dreams. So I wrote a play called The Secret Place, in which a black cop infiltrates a revolutionary group. And he finally gets made. And in it, you couldn't just be serious, I had a couple of jokes. And when Lorne [Michaels] read it, he called me and said, "I want you to be a writer."

To make it very short, I had a lot of problems writing [sketches that were] 15 seconds, 30 seconds, a minute. Because a play, you can write two hours. And that's what I was accustomed to. And I didn't get it together until I realized that in my play, I did have a joke about white liberalism, and how you had a group fundraising that was all Black, [you'd raise] a certain amount of money. But if you had some white people in there, in the '50s and '60s, you got a whole lot of more money, because of white liberalism.

And I realized that was a funny joke, and I told it to the wrong person. That person told to somebody else who actually stole it, wrote it as [the SNL sketch] "White Guilt Relief Fund." It made me angry. And I was really going to do something I shouldn't have done. One day I walked in—I was going to confront this guy. And when I walked out of the elevator, somebody said, "Garrett, Lorne Michaels wants to see you in the green room." I go to the green room and he's actually looking at the movie Cooley High, that I was one of the stars in.

Lorne wanted a Black person on the Not Ready for Prime Time players. And so John and Gilda and Jane and them said, "You got [Garrett]—he's an actor, too." Lorne said, "Well, prove it." And they got the movie and they looked at it. When Lorne saw the movie, he asked me to audition for the Not Ready for Prime Players. I auditioned, and I got it.

After the first year, I was never officially a writer, although I did write after that. I'd been told I was no longer a writer, but Lorne said, "If you want to contribute something, do." So I did contribute some stuff. I did a thing called "Get Me a Shotgun and Shoot All the Whiteys I See." I did some other stuff, too. But only in the first year was I officially a writer.

What was your favorite sketch that you wrote, or your favorite sketch that you appeared in?

Well, my favorite thing was collecting a check, okay?

But I liked the people. I liked John, Gilda—all of them were so talented. I was just amazed at the talent, the ability. The band. I loved the band. But I guess one of my favorite would be the thing I did with Chevy—News for the Hard of Hearing. And Chico Escuela, the Mets baseball guy.

What was the hardest part?

Well, actually what I just said was one of the hardest things. The disappointment that I didn't do what I should have been doing as a writer. Because it took me a long time to figure out how to bring it down from two hours and just write for 15 seconds to 30 seconds.

I made some bad choices. After the show, you should go and hang out with the cast and build friendships. And at that time, I was a serious introvert. So after the show, I would go home. And that's the one thing I learned, was that people can form certain attitudes if you're not hanging out. They may think you think you got your nose in the air or something like that.

So I'm sure I created an impression—but I really had serious introversion. So after the show, I would just go home. But the major thing I regretted is that I did not get it together in terms of being able to write shorter pieces. I was amazed at how some of the writers could say things that were really delivering a punch in 30 seconds.

When did you realize that this show was connecting with people and becoming a phenomenon? Did you start getting recognized on the street in New York?

Oh, it took me about a year, a year and a half to realize where it was going. I sort of didn't invite it because of my introverted thing. That, probably, was misinterpreted by a whole lot of people. I'm no longer that way. I'm very, very gregarious now—but yeah, that started to happen. People look at you in a different kind of way and even quote some of the stuff you did [on the show] and stuff like that. That was a different thing for my life. And at a certain point you realize that people place a lot of responsibility on you that you didn't ask for.

In what sense? Because you were the only Black cast member?

Yes. People see you there, and they've never seen you before. A whole lot of them didn't know who I was and wondered where Lorne Michaels had got this strange Black guy. Although these people were not with you when you were struggling, and couldn't pay your rent, as soon as they see you, they have a proprietary kind of attitude towards you. As if you're somehow supposed to do what they think is the right thing to do.

So you felt that there was pressure on you, from your own people, to represent Black people in a certain light?

Oh without a doubt, without a doubt. I got a letter from the NAACP.

About Saturday Night Live?

Yeah. I don't remember the letter explicitly, but basically it was telling me to straighten up and fly right. Basically you have a right to disagree with my comedic choices, but in my opinion, you have no right to make some stereotypical conclusion about my character, my personality, none of that. You have no right to do that.

What was it like inside SNL, from that standpoint? This was the mid-'70s. I have to assume nobody was PC, nobody was woke—especially a bunch of white comedy writers.

Well, Lorne Michaels [has] zero racism, but some of the writers he hired had a little bit of it going.

Did you feel that in some of the material they were giving you to play?

I felt that they deprived me of the writing. But by the same token, thank God for Alan Zweibel, who wrote for me. Chevy Chase wrote for me. A couple of people stepped up and started writing for me. But it would not be true to say there was no racism among some of the writers. There was.

You've said before that you felt like you'd get slotted into stereotypical roles, in terms of what you were given to do on the show.

I'll give you an example. Michael O'Donoghue. Brilliant man, who was hooked up with National Lampoon. And I knew that. But I met him and stuff started happening, and I said, Uh-oh.

One time, there was a role in this skit for a doctor and it hadn't been cast, so I suggested that I should do it. And Michael's response was, "Well, Garrett, people will be thrown by a Black doctor." Now imagine. I come from New Orleans, where not only you have Black medical doctors galore, but you have Black PhDs as well. Not only that, in '75 you had them in Mobile, you had them in Chicago, you had them in Houston, you had them in Los Angeles.

And definitely you had 'em in New York City where Saturday Night Live was. Of course there were Black doctors all over New York City in '75. Yet his response—a man who was associated with one of the progressive institutions in the country, National Lampoon—this guy said that to me. And not that he wasn't a brilliant man—he was. But Wagner was a brilliant man, right? He hated the Jews.

A lot of incredible people passed through those halls when you were there. Is there an encounter that really stands out in your memory, with a guest host or some other person who came on the show?

Here's something I remember—I am to this day, so regretful that he passed. Prince. Prince was doing the 15th anniversary show [in 1989.] And I was standing at a door that was across from the dressing room where he was. I knew he was going to do the show, but I didn't realize he was there. He opens the door, he sees me, and Prince very carefully walked over to me, reached out his hand and said, "Garrett, thank you very much." And then he went back to his room. That's something I'll never forget.

Paul Simon. Candace Bergen. What's his name? Oh, shit—the seven words you can't speak.

Oh—George Carlin.

George Carlin. And of course the first Black person [to host SNL] was Richard Pryor. And I looked forward to working with him, but Richard brought his own group [of writers and actors.]

Richard didn't know who I was. And the people around him basically said, "Don't use him. When you go to the show, bring your own group." To this day, I regard Richard as the most creative, astounding, incredible monologuist I've ever heard. So at that time, I was looking forward to working with him. But then I didn't, because he didn't know me. We both were coke fiends at the time, so I sort of understood where he was coming from. But he had drawn a conclusion about me that was, in my opinion, not true.

And so, I remember that, because I remember not being able to work with the guy I [was] greatly looking forward to working with. But then he made it up to me when he did a movie later on, when I was in California. He was doing a movie called Critical Condition. And he actually had [director] Michael Apted call me, and he wrote a part for me in that movie. And I rode around in his Maserati.

Have you ever ridden in a Maserati? It is the most uncomfortable expensive ride you're ever going to have, okay? I knew it cost a lot of money, but I said, "What the fuck? Give me my Cadillac. I grew up with Cadillacs. Okay? I have a Cadillac now, a red Cadillac. I speed on the 405 in a red Cadillac, to prove that I'm a very, very brave Black man. Because just being in that car might get the cops coming up.

Anyway—Richard Pryor is one I remember.

But at that time, you and him had some of the same recreational interests, you would say?

Yes, we did. Yes, we did. Yes, we did. Yes, we did. Yes.

When you started using cocaine, how much of that was about managing the anxiety and the pressures of the Saturday Night Live experience for you?

No. I mean, psychologically, you can look back to that, but at the time? I had never even smoked a joint until I was 33. So all this was new to me, and it couldn't be interpreted in that way. Yeah, it can be. But I wasn't saying, "Hey, I'm upset, let me sniff." It was just the effect of it—I was sort of hooked on it.

It's not a choice that I am proud of, but it is a choice and I don't shy away from talking about it, saying I did make that choice. And when I was in it, I was 100% in it. It took me a little while to a lot to accept that it was a bad choice and a little while to get out of it. I haven't seen cocaine since about 2000, something like that.

Good for you, man.

Although, let me say: With cocaine, the only problem is they extract the cocaine from the leaf. If you go to Peru and walk in the hills, you see coca leaves. You can eat those and those are healthy. Matter of fact, that's what the old guys do all the time. Then they walk about 75 miles, okay?

I bet they do.

But if you take it out of the leaf, that's when it becomes acidic and then attacks tissues and causes deviated septums. And after that, you're not sniffing in your nose, then you're going to start putting it on your gums. Your gums are gone, your teeth are going to fall out a lot. By the way, did you know your man Sigmund Freud was a cocaine addict?

I did, yeah. It explains a lot.

I was about to say the same thing. I said, "Oh, that's where all that shit comes from."

You mentioned Pryor. This is a random question, but did you have anything to do with Sun Ra and the Arkestra getting booked as a musical guest? Did you happen to interact with him at all when he was on the show?

Oh, man. Here's what I did. I used to live on 5th Street. Sun Ra had an apartment on Second Street. I had never heard of his ass, okay? Or I'd heard of him, I'd heard of him over and over again, but I'd never seen him. And I go to his apartment, and I walk up and it's all pretty and stuff, made up with all kinds of cloth hanging everywhere, right? And there's a jar on the side. You contribute whatever you want to contribute, right?

So I give him, I don't know, $5, and I go up there and this guy comes out in a robe. And he says some shit that I don't remember. And he starts playing, right? And I'm not being knocked out, but he's playing looking at me, okay? You know what he does? He turns around, Sun Ra does. He turns his back to the fucking organ and plays it with his back to it. I had never seen anybody do that. I [kept coming back] for at least three or four weeks, and then he disappeared. But to answer your question about him being on the show—no, that wasn't me. But if he had asked me, I would've said, "Hell yeah."

Do you understand music? You know what I mean when I say 12 tone?

Yeah, like Schoenberg. Sure.

Yeah. He played blues and he played 12 tone in the same motherfucking concert. With his back to the organ. I said, "Damn, bro." I said, "Shit—Mozart ain't shit."

This is the question that makes everybody go "Oh, man..." when I ask it: If you can only pick one person, who is the funniest person in the history of Saturday Night Live?

Oh, man. Well, Richard. I would say him doing that name calling thing with Chevy is one of the classic comedic renderings by anyone. You know what I'm talking about?

"Dead honky." Of course.

Dead Honky. Chevy says "N-gger" and Richard says "Dead honky!" I would say that is a classic, that at least with some other stuff [is up there with everything] they've ever done. And it also has a lot more—a friend of mine gave me this word—a lot more sauce, the kind of sauce that was there in the first five, ten years, which is not there now.

You're talking about them taking risks in the writing—touching on racial tension and things like that?

Talking about religious stuff, talking about political stuff that really hits hard on either side. Because that was another thing about Saturday Night Live, they didn't care whether you're Democrat or Republican. If your ass was doing something, they were gonna show foibles. They were going to roast your ass.

How'd you feel about the movie Saturday Night, by the way? Did you like how you were represented?

Well, I like Lamorne [Morris, who played Garrett in the film]. I liked what he did. He won the Emmy for another show he was in called Fargo.

Yeah. He was great in that.

He and I had a long talk on Zoom before he did the movie. But when I met him, he looked sort of familiar, and his name was Morris, so I had to ask him. I said, "Lamorne, may I see your mother please?" And he showed me [a picture] of his mother. And when she met me, she said, "Remember me?"

Come on.

Yes, she did. Yes she did. [laughs]

He did a beautiful job. I thought they tried to do something very difficult. One day, all those characters, man. I would think you need more time to do it right. But I commend them for trying to do what they did.