Why Can’t You Pack a Bag?

Open QuestionsOur overstuffed suitcases burden us more than we realize.By Joshua RothmanDecember 17, 2024Illustration by Josie NortonI had my worst-ever packing experience in the late nineties, when I was a teen-ager. My mother and I were returning from a trip to Ireland. Before leaving home, we’d overpacked extravagantly, imagining a wide range of non-rainy weather conditions; I’d also, for some reason, decided that I needed to bring not just my Discman but a whole booklet of CDs. We were already at capacity when, the day before our return flight, my mom went to the local butcher shop and bought two dozen sausages, a few rashers of bacon, and several cans of stew. Her idea was to wrap everything in plastic bags and hide them inside our giant duffel of laundry. The dogs and the customs agents at Dulles Airport were not deceived. As we knelt on the terminal linoleum, surrounded by sausages and stuffing our clothes back into our bags, I felt a genuine sense of public shame, as though I were in a stockade.It’s obvious why packing is hard: it involves a series of mounting yet tedious questions. What, how many, which one, in what? What if, what about, how will I, what then? You can respond by trying to pack everything, accepting in advance the consequences in weight and disorganization. Or you can attempt to work out answers in detail, through a rational thought process that often brings you up against the limits of what’s knowable. It’s true, for example, that it rains a lot in Ireland in October—but, during that month last year, there were actually a few days when it was sunny and in the seventies. So perhaps a pair of shorts is sensible? And a sun hat? And maybe it’s impossible, ultimately, to predict the future, and so some sandals might make sense, too?After the sausage misadventure, I told myself that I’d learn to pack better. A few years later, when I had to spend a month in a Los Angeles hotel room with my mom, who’d be recovering from brain surgery, I bought a forty-litre backpack from the outdoor company Osprey and resolved to fit everything I needed into it. I succeeded—and yet the packed bag was so heavy, and my stuff so rumpled and squished, that it was clear I’d gone wrong. Over the next several years, on trips to Japan, Turkey, and France, I confined myself to a single giant rolling suitcase. But I hated dragging it through puddles or along cobbled streets—and, the more I used it, the unhappier I was with the whole wheeled-bag gestalt. Travel is symbolic, and bad packing undermines the sense of freedom it ideally brings. Why travel, I thought, only to be confined to smoothly paved surfaces? I dreaded the inevitable moment when my overstuffed bag would tip over with a thud, then rock back and forth like a turtle stuck on its shell. My own stuff was working against me, and I couldn’t help but take it personally.A packer faces three obstacles. There’s contingency: a variety of possible futures must somehow be tamed. There’s consumerism: the junk you own needs to be winnowed into a useful curation. And there’s comfort: we want to be cushioned against transit’s sharp points. Staring down these monsters can be unpleasant. It’s embarrassing to realize that you live in uncertainty despite your hoard of objects, and to admit that you need your blanket. Maybe, if you were someone who could roll with the punches, and who lived a tougher, less acquisitive life, packing would be easier. So there’s actually a fourth obstacle: you.What sort of person is good at packing? Joan Didion has a famous packing list, which she included in her book of essays “The White Album”: basically, two skirts, two shirts, one sweater, two pairs of shoes, stockings, some underwear, a robe, slippers, toiletries, a mohair throw, legal pads, files, a typewriter, some cigarettes, a bottle of bourbon, and her house key, all in two bags, one to check, one to carry. The list is often recirculated in articles about how to “pack like Joan Didion.” It’s the cool school of packing: the idea isn’t that we want to pack like Joan, but that, if we were sharp, sleek, and discerning, like her, we might also travel like her, as a kind of effortless bonus. For a while, I pursued this strategy. It always seemed to be working until, at the last minute, I’d add things to the bag. I lacked Joan’s confidence.Eventually, I found a new role model: a guy named Tynan, whom I’d never met but whose blog I often visited. A “minimalist nomad,” Tynan did whatever he did for a living by working remotely, mostly from cruise ships, which he claimed were ideal work environments. (On one boat, he worked from “a perfect lounge in which a string quartet played for four hours each day.”) He seemed to live mostly out of a single small backpack, and to own only one of everything—one button-down, one T-shirt, one pair of pants, one down jacket, one rain shell. Most of his clothes were made out of durable materials that could be washed and dried overnight.Tynan was nerdy, not c

I had my worst-ever packing experience in the late nineties, when I was a teen-ager. My mother and I were returning from a trip to Ireland. Before leaving home, we’d overpacked extravagantly, imagining a wide range of non-rainy weather conditions; I’d also, for some reason, decided that I needed to bring not just my Discman but a whole booklet of CDs. We were already at capacity when, the day before our return flight, my mom went to the local butcher shop and bought two dozen sausages, a few rashers of bacon, and several cans of stew. Her idea was to wrap everything in plastic bags and hide them inside our giant duffel of laundry. The dogs and the customs agents at Dulles Airport were not deceived. As we knelt on the terminal linoleum, surrounded by sausages and stuffing our clothes back into our bags, I felt a genuine sense of public shame, as though I were in a stockade.

It’s obvious why packing is hard: it involves a series of mounting yet tedious questions. What, how many, which one, in what? What if, what about, how will I, what then? You can respond by trying to pack everything, accepting in advance the consequences in weight and disorganization. Or you can attempt to work out answers in detail, through a rational thought process that often brings you up against the limits of what’s knowable. It’s true, for example, that it rains a lot in Ireland in October—but, during that month last year, there were actually a few days when it was sunny and in the seventies. So perhaps a pair of shorts is sensible? And a sun hat? And maybe it’s impossible, ultimately, to predict the future, and so some sandals might make sense, too?

After the sausage misadventure, I told myself that I’d learn to pack better. A few years later, when I had to spend a month in a Los Angeles hotel room with my mom, who’d be recovering from brain surgery, I bought a forty-litre backpack from the outdoor company Osprey and resolved to fit everything I needed into it. I succeeded—and yet the packed bag was so heavy, and my stuff so rumpled and squished, that it was clear I’d gone wrong. Over the next several years, on trips to Japan, Turkey, and France, I confined myself to a single giant rolling suitcase. But I hated dragging it through puddles or along cobbled streets—and, the more I used it, the unhappier I was with the whole wheeled-bag gestalt. Travel is symbolic, and bad packing undermines the sense of freedom it ideally brings. Why travel, I thought, only to be confined to smoothly paved surfaces? I dreaded the inevitable moment when my overstuffed bag would tip over with a thud, then rock back and forth like a turtle stuck on its shell. My own stuff was working against me, and I couldn’t help but take it personally.

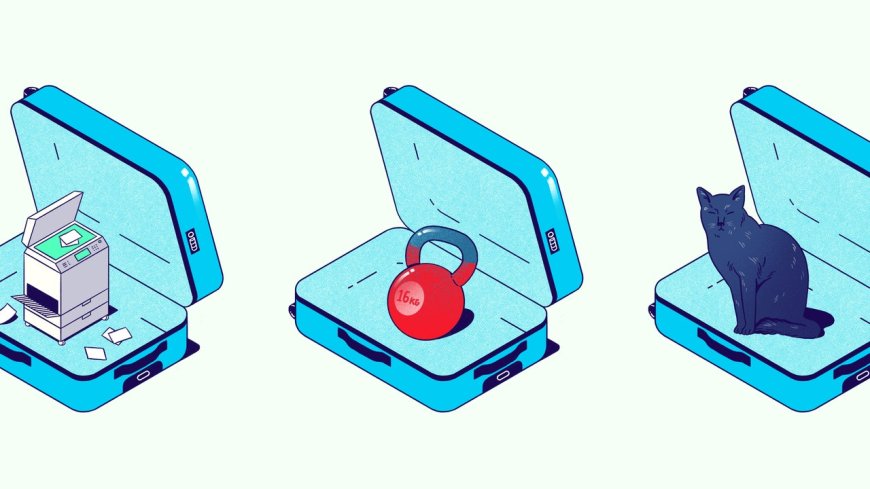

A packer faces three obstacles. There’s contingency: a variety of possible futures must somehow be tamed. There’s consumerism: the junk you own needs to be winnowed into a useful curation. And there’s comfort: we want to be cushioned against transit’s sharp points. Staring down these monsters can be unpleasant. It’s embarrassing to realize that you live in uncertainty despite your hoard of objects, and to admit that you need your blanket. Maybe, if you were someone who could roll with the punches, and who lived a tougher, less acquisitive life, packing would be easier. So there’s actually a fourth obstacle: you.

What sort of person is good at packing? Joan Didion has a famous packing list, which she included in her book of essays “The White Album”: basically, two skirts, two shirts, one sweater, two pairs of shoes, stockings, some underwear, a robe, slippers, toiletries, a mohair throw, legal pads, files, a typewriter, some cigarettes, a bottle of bourbon, and her house key, all in two bags, one to check, one to carry. The list is often recirculated in articles about how to “pack like Joan Didion.” It’s the cool school of packing: the idea isn’t that we want to pack like Joan, but that, if we were sharp, sleek, and discerning, like her, we might also travel like her, as a kind of effortless bonus. For a while, I pursued this strategy. It always seemed to be working until, at the last minute, I’d add things to the bag. I lacked Joan’s confidence.

Eventually, I found a new role model: a guy named Tynan, whom I’d never met but whose blog I often visited. A “minimalist nomad,” Tynan did whatever he did for a living by working remotely, mostly from cruise ships, which he claimed were ideal work environments. (On one boat, he worked from “a perfect lounge in which a string quartet played for four hours each day.”) He seemed to live mostly out of a single small backpack, and to own only one of everything—one button-down, one T-shirt, one pair of pants, one down jacket, one rain shell. Most of his clothes were made out of durable materials that could be washed and dried overnight.

Tynan was nerdy, not cool—in other words, he was more on my wavelength. Through him, I discovered the world of “onebag” packing, a subculture centered on the pursuit of things like the tiniest possible battery charger, or the ideal multipurpose sweater. The promise of onebagging was that everything you needed for even the longest trip could fit into a backpack small enough to slide under the seat in front of you on the plane. Its most ardent practitioners posted after-action trip reports, in which they painstakingly reviewed every piece of packed gear, speculating about how it could be further miniaturized. A subreddit dedicated to “zerobagging” pushed the idea even further, with users trying “the no baggage challenge.” (A jacket with pockets was often key.)

It turned out that I enjoyed thinking of packing as a game, rather than as a chore. In the course of several years, during which I travelled often as a reporter, I put together a four-season “capsule wardrobe,” in which everything was made of either merino wool or technical fabric. I bought a single small backpack and assembled a system of packing cubes and little pouches for squaring everything away. I found smaller versions of my gadgets; standardized and streamlined my chargers and cables; set up a small travel toiletry kit, which I kept stocked even at home; and carefully wrote out detailed packing lists for winter, spring, summer, and fall. It was a consumerist endeavor, but it had an end point.

During this period, packing became, in a strange way, my main hobby. At the time, I had an exceptionally long commute—two hours by train, each way, to the New Yorker offices—and, more and more, I found myself living as though I were always travelling. I wore my travel wardrobe nearly every day, because it was simple and comfortable, and used my travel Dopp kit while getting ready after the gym. In a book called “The Comfort Crisis: Embrace Discomfort to Reclaim Your Wild, Happy, Healthy Self,” the writer Michael Easter argues that our addiction to being comfortable hems us in more than we acknowledge. He focusses on professional athletes, monks, and outdoor adventurers, but I found that a willingness to be uncomfortable made even ordinary travel—and ordinary life—easier and in many respects better. Because I couldn’t fit another layer into my small pack, I shivered while waiting for the train—but so what? There was pleasure in packing’s constraints. A creeping asceticism flowed into my life, from my bag outward. Meanwhile, when I went on a reporting trip—even a long one, covering a few foreign cities—I simply added a little more to the bag and left, as I would on any other day.

Many basically ordinary activities conceal, or can conceal, vast amounts of effort. Packing, for me, has turned out to be like staying fit, or being well read, or cooking a decent weeknight dinner for a family of four, in that it requires a surprising amount of consistent work over time. The effort isn’t just practical but intellectual. You’re a better packer, for instance, when you master the concept of a “distinction without a difference”: just as there’s only a hollow distinction (not a real difference) between telling a lie and asserting an “alternative fact,” there might be no appreciable difference between two distinctive-seeming garments (your navy sweater with the quarter-zip, say, and your black sweater with the button neck). You also improve when you truly internalize the notion of decision fatigue. We all know, from firsthand experience, that making choices takes energy, but the surprising thing, substantiated by research, is that decision fatigue is cumulative: the more decisions you have to make, the worse you become at making them. Overpacking has the effect of deferring decisions, shifting them from your house to your hotel room. When you understand this, you become more motivated in your packing: it’s senseless to add not just to your physical load but to your mental one.

It could be that the best way to pack is simply to stay packed. If you repacked your bag as soon as you returned, you could eliminate the decisions involved in packing almost entirely. I haven’t quite reached that level of packing zen, but I’m close: my packing is so standardized, and I have so much pre-packed, that getting ready for almost anything now takes me about fifteen minutes. It’s a limited victory. These days, with two small kids, I rarely travel more than a few miles from my house, which is a bedlam of loose Legos and orphaned remote-control cars. When we do go somewhere as a family, my tidily packed bag is like a drop of rain in a sea of luggage.

On the other hand, becoming a master packer has taught me an important lesson: success is possible. My new goal is to become as organized in life as I am on the road; my hope is that packing will end up being a kind of laboratory for the development of a more rational me. A well-packed bag has a certain look. The zippers run without bulging; the compartments maintain their proportions; the fabric keeps its shape. Couldn’t everything else be that way, too? ♦