What Happens When a Sober Influencer Relapses?

WellnessA wave of content creators has made abstinence a core part of their online identity—and some of them are continuing to share when things go off the rails.By Matthew HerskowitzNovember 3, 2024Save this storySaveSave this storySaveOur culture produces influencers for every imaginable product and lifestyle, and recovery from addiction to drugs and alcohol is no different. Some sober influencers satirize their addiction, relating sordid tales of the lengths they’d go to to score their next hit. Others appeal to their fanbase with abstract motivation—inspirational quotes against a pretty background—while still others are more earnest and practical, providing tips for resisting cravings and recipes for mocktails. Some, distancing themselves from wellness culture, reveal the messy sides of sobriety.You can date the advent of contemporary sobriety culture to the 1930s, when the Twelve Steps were first formulated. Now, sobriety is more of a spectrum—it can mean many things to different people. And the gamut of vices—drugs, alcohol, sex, gambling—have their own built-in communities of sober people, who convene both in person and, increasingly, online.But the digital attention economy is demanding, and recovery on the internet has become, to some, a spectator sport, one in which it can seem like a competition to see who can garner the greatest number of views, likes, and subscribers. Given the unfortunate reality that the vast majority of people in recovery will relapse at some point in their journey, what does it mean when that happens to someone whose personal brand hinges on not drinking or using?In some cases, an online audience can be a source of support. After one sober influencer named Molly, who goes by @sobergalx on TikTok (and asked to be identified only be her first name), revealed a relapse in a video that has since been viewed nearly 4 million times, she continued to document her recovery, and says her online community largely rallied behind her.Similar vulnerabilities about their recovery journeys (and slip-ups) have allowed sober content creators Connor Duffy and Will Milligram to amass over half a million followers and open their own recovery house. “Addicts have to channel their energy somewhere,” Duffy told me. “What better way to channel it than to help someone out who’s going through something so insurmountable?”To Anna Lembke, professor of psychology at Stanford and the author of Dopamine Nation, this dynamic makes sense—a huge part of addiction recovery is having a fellowship of individuals. “It’s a contagious phenomenon,” she said. This makes social media a potentially-helpful venue for proselytizing sobriety. However, she also warned that social media can also be “antithetical to the process of sobriety, which is in many ways a process of renunciation.” For sober influencers, she continued, what generally starts as a way of helping feel less alone in addiction and recovery has the potential to become a way to replace one addictive behavior with another.One sobriety influencer, Toni Becker, who posts as @toniquinne on Instagram, knows this firsthand. Becker only started seriously making content nine years into her recovery from addiction to crystal meth. She gained a following primarily for her satirical videos, which documented her running from “shadow people” while in the throes of meth psychosis. “Initially I hoped that this could provide some way of showing people in active addiction that recovery is possible,” she said. But with virality came the wrath of trolls who would issue death threats, and deny that she was actually sober. “I became obsessed with checking the likes and comments on everything. It was horrible for my recovery.” While she continued to make videos, she began to devolve into active psychosis. “It was like I had relapsed, but I wasn’t actively using.”Becker took a break from social media and began treatment for her mental health, eventually recovering and refiguring her relationship with social media. “Now, I have very strict and specific limits with my followers. I never check the likes or comments on anything, and take routine breaks.”Becker has not herself documented a relapse online, but she’s aware of the difficulty it can pose for creators. “It’s like you’re walking in somewhere with your tail tucked between your legs—the sense of failure is overwhelming,” she said. “I could relapse tomorrow. I can’t even count the number of online personalities who have relapsed.” But to her, this isn’t a shameful failure so much as an authentic view of recovery: “What’s important is that these stories be told.”

Our culture produces influencers for every imaginable product and lifestyle, and recovery from addiction to drugs and alcohol is no different. Some sober influencers satirize their addiction, relating sordid tales of the lengths they’d go to to score their next hit. Others appeal to their fanbase with abstract motivation—inspirational quotes against a pretty background—while still others are more earnest and practical, providing tips for resisting cravings and recipes for mocktails. Some, distancing themselves from wellness culture, reveal the messy sides of sobriety.

You can date the advent of contemporary sobriety culture to the 1930s, when the Twelve Steps were first formulated. Now, sobriety is more of a spectrum—it can mean many things to different people. And the gamut of vices—drugs, alcohol, sex, gambling—have their own built-in communities of sober people, who convene both in person and, increasingly, online.

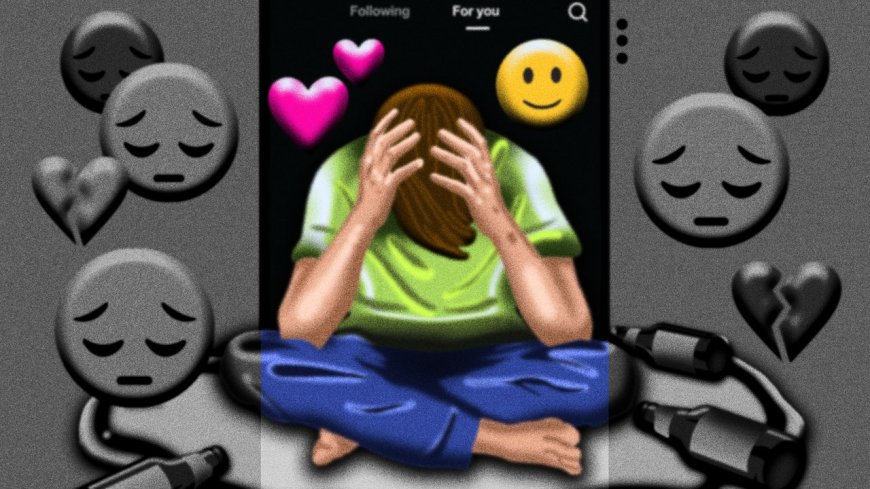

But the digital attention economy is demanding, and recovery on the internet has become, to some, a spectator sport, one in which it can seem like a competition to see who can garner the greatest number of views, likes, and subscribers. Given the unfortunate reality that the vast majority of people in recovery will relapse at some point in their journey, what does it mean when that happens to someone whose personal brand hinges on not drinking or using?

In some cases, an online audience can be a source of support. After one sober influencer named Molly, who goes by @sobergalx on TikTok (and asked to be identified only be her first name), revealed a relapse in a video that has since been viewed nearly 4 million times, she continued to document her recovery, and says her online community largely rallied behind her.

Similar vulnerabilities about their recovery journeys (and slip-ups) have allowed sober content creators Connor Duffy and Will Milligram to amass over half a million followers and open their own recovery house. “Addicts have to channel their energy somewhere,” Duffy told me. “What better way to channel it than to help someone out who’s going through something so insurmountable?”

To Anna Lembke, professor of psychology at Stanford and the author of Dopamine Nation, this dynamic makes sense—a huge part of addiction recovery is having a fellowship of individuals. “It’s a contagious phenomenon,” she said. This makes social media a potentially-helpful venue for proselytizing sobriety. However, she also warned that social media can also be “antithetical to the process of sobriety, which is in many ways a process of renunciation.” For sober influencers, she continued, what generally starts as a way of helping feel less alone in addiction and recovery has the potential to become a way to replace one addictive behavior with another.

One sobriety influencer, Toni Becker, who posts as @toniquinne on Instagram, knows this firsthand. Becker only started seriously making content nine years into her recovery from addiction to crystal meth. She gained a following primarily for her satirical videos, which documented her running from “shadow people” while in the throes of meth psychosis. “Initially I hoped that this could provide some way of showing people in active addiction that recovery is possible,” she said. But with virality came the wrath of trolls who would issue death threats, and deny that she was actually sober. “I became obsessed with checking the likes and comments on everything. It was horrible for my recovery.” While she continued to make videos, she began to devolve into active psychosis. “It was like I had relapsed, but I wasn’t actively using.”

Becker took a break from social media and began treatment for her mental health, eventually recovering and refiguring her relationship with social media. “Now, I have very strict and specific limits with my followers. I never check the likes or comments on anything, and take routine breaks.”

Becker has not herself documented a relapse online, but she’s aware of the difficulty it can pose for creators. “It’s like you’re walking in somewhere with your tail tucked between your legs—the sense of failure is overwhelming,” she said. “I could relapse tomorrow. I can’t even count the number of online personalities who have relapsed.” But to her, this isn’t a shameful failure so much as an authentic view of recovery: “What’s important is that these stories be told.”