Sebastian Mallaby on Finance’s Intellectual Adventure Stories

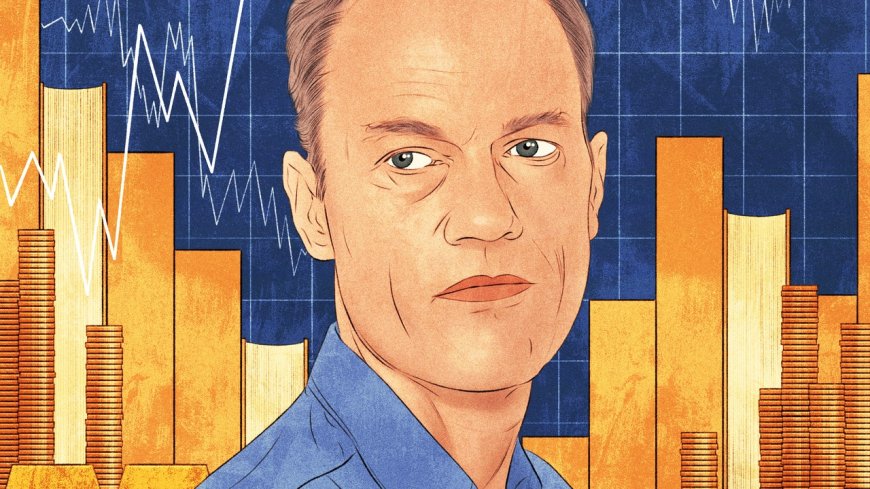

Book CurrentsThe world might love to hate financiers, but the worlds of hedge funds, venture capital, and central banking can be filled with thrilling ideas and human dramas.January 8, 2025Illustration by Isabel Seliger; Source photographs by David Levenson / GettyYou’re reading Book Currents, a weekly column in which notable figures share what they’re reading. Sign up for the Goings On newsletter to receive their selections, and other cultural recommendations, in your in-box.Sebastian Mallaby is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of five books, including, most recently, “The Power Law,” an account of the venture-capital industry. A former Washington Post and Economist journalist, Mallaby understands why people love to hate financiers: “The prominent ones are crazy rich; they appear to be shuffling numbers rather than making useful things; and periodically they cause spectacular bubbles and crashes.” But, he contends, this dismissal fails to account for the fact that society needs experts to decide where resources should flow—and that finance is littered with “intellectual adventure stories.” Not long ago, Mallaby recommended to us a few of the best books about such tales. His remarks—a mix of written correspondence and conversation—have been edited and condensed.When Genius Failedby Roger LowensteinAmazon | BookshopIn 1998, the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management collapsed after it lost a complex series of bets that it had made, using borrowed money, on global bond markets. These bets generally worked out fine in calm times, but not if something unexpected happened—as it did that summer, when Russia defaulted on its sovereign debt.L.T.C.M.’s collapse would have been easy for a writer to demonize in a crude way. It had all the elements of financial villainy: a bunch of greedy quants sequester themselves in a secretive office in Connecticut and almost bring Western economies to their knees. What’s great about Lowenstein’s book is that he describes not just the failure to which his title refers; he also describes the genius. The fund’s team included two Nobel Prize winners and some of the shrewdest figures to emerge from Wall Street. Its founder, John Meriwether, was renowned for helping the storied bond-trading house Salomon Brothers shift from old-school, non-quantitative traders to a more mathematical and analytical tribe.In human terms, Lowenstein’s book is a portrait not of villainy but of hubris—and it’s the sort of hubris, moreover, that would have seemed more like well-earned confidence until everything went wrong. I try in my own writing to tell the truth with sympathy. “When Genius Failed” achieves this balance beautifully.Zero to Oneby Peter Thiel, with Blake MastersAmazon | BookshopBy 2016, I had written a book on development finance, a book on hedge funds, and a book on central banking.I knew I wanted to write about another financial specialty, and it struck me that the most interesting—because it’s the most weird—is venture capital. In venture capital, none of the conventional ways of valuing an asset work. You can’t apply them to a startup that consists of a couple of two-legged mammals who walk into your office with a dream. You have to invent a new way of thinking about its value.When I was first trying to wrap my head around this strange specialty, Peter Thiel’s book was invaluable. It’s a short volume, derived from a set of lectures rather than a carefully researched historical narrative, but it unpacks a lot of what makes Silicon Valley tick. Among these is the idea of the power law, which holds that the vast majority of profits and societal impact generated by startups will come from a small handful of entrepreneurs. This concept seemed to me to be so fundamentally important that I borrowed the phrase for the title of my own book.Another idea, which follows from the power law, is that, because only one or two bets out of ten generate all of a V.C.’s profits, those bets really have to be unusual. The founders’ proposal has to be “We are going to do something so difficult and unlikely that nobody else is going to do it—and therefore, if we manage to, we will dominate this class of product.” Among other ideas, what springs from that is the notion that you should back contrarian weirdos—the type of person who would have built a bomb in high school, or something equally odd.Volckerby William L. SilberAmazonWhen I was working on my biography of Alan Greenspan, I was influenced by this portrait of Paul Volcker, who led the Federal Reserve between 1979 and 1987, before Greenspan took over.I think that if you did a quick-association test on people in economics, asking them who the most revered U.S. central-bank chair is, Volcker would probably win. I don’t quibble with that verdict, because he brought down very high peacetime inflation, and that victory stuck for four decades. That’s a pretty big achievement.Volcker is often thought of as a sort of anti-Greenspa

Sebastian Mallaby is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of five books, including, most recently, “The Power Law,” an account of the venture-capital industry. A former Washington Post and Economist journalist, Mallaby understands why people love to hate financiers: “The prominent ones are crazy rich; they appear to be shuffling numbers rather than making useful things; and periodically they cause spectacular bubbles and crashes.” But, he contends, this dismissal fails to account for the fact that society needs experts to decide where resources should flow—and that finance is littered with “intellectual adventure stories.” Not long ago, Mallaby recommended to us a few of the best books about such tales. His remarks—a mix of written correspondence and conversation—have been edited and condensed.

When Genius Failed

by Roger Lowenstein

In 1998, the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management collapsed after it lost a complex series of bets that it had made, using borrowed money, on global bond markets. These bets generally worked out fine in calm times, but not if something unexpected happened—as it did that summer, when Russia defaulted on its sovereign debt.

L.T.C.M.’s collapse would have been easy for a writer to demonize in a crude way. It had all the elements of financial villainy: a bunch of greedy quants sequester themselves in a secretive office in Connecticut and almost bring Western economies to their knees. What’s great about Lowenstein’s book is that he describes not just the failure to which his title refers; he also describes the genius. The fund’s team included two Nobel Prize winners and some of the shrewdest figures to emerge from Wall Street. Its founder, John Meriwether, was renowned for helping the storied bond-trading house Salomon Brothers shift from old-school, non-quantitative traders to a more mathematical and analytical tribe.

In human terms, Lowenstein’s book is a portrait not of villainy but of hubris—and it’s the sort of hubris, moreover, that would have seemed more like well-earned confidence until everything went wrong. I try in my own writing to tell the truth with sympathy. “When Genius Failed” achieves this balance beautifully.

Zero to One

by Peter Thiel, with Blake Masters

By 2016, I had written a book on development finance, a book on hedge funds, and a book on central banking.

I knew I wanted to write about another financial specialty, and it struck me that the most interesting—because it’s the most weird—is venture capital. In venture capital, none of the conventional ways of valuing an asset work. You can’t apply them to a startup that consists of a couple of two-legged mammals who walk into your office with a dream. You have to invent a new way of thinking about its value.

When I was first trying to wrap my head around this strange specialty, Peter Thiel’s book was invaluable. It’s a short volume, derived from a set of lectures rather than a carefully researched historical narrative, but it unpacks a lot of what makes Silicon Valley tick. Among these is the idea of the power law, which holds that the vast majority of profits and societal impact generated by startups will come from a small handful of entrepreneurs. This concept seemed to me to be so fundamentally important that I borrowed the phrase for the title of my own book.

Another idea, which follows from the power law, is that, because only one or two bets out of ten generate all of a V.C.’s profits, those bets really have to be unusual. The founders’ proposal has to be “We are going to do something so difficult and unlikely that nobody else is going to do it—and therefore, if we manage to, we will dominate this class of product.” Among other ideas, what springs from that is the notion that you should back contrarian weirdos—the type of person who would have built a bomb in high school, or something equally odd.

Volcker

by William L. Silber

When I was working on my biography of Alan Greenspan, I was influenced by this portrait of Paul Volcker, who led the Federal Reserve between 1979 and 1987, before Greenspan took over.

I think that if you did a quick-association test on people in economics, asking them who the most revered U.S. central-bank chair is, Volcker would probably win. I don’t quibble with that verdict, because he brought down very high peacetime inflation, and that victory stuck for four decades. That’s a pretty big achievement.

Volcker is often thought of as a sort of anti-Greenspan: he ran a tough monetary policy, rather than allowing loose monetary policy to stoke financial bubbles, and he was instinctively disapproving of risk-seeking financiers. What I love about Silber’s book is that, while being sympathetic, it deflates some of the Volcker legend, showing the great man for what he really was. He was not a perfect model of regulatory toughness, and his monetary policy was as much improvised as principled. His legacy includes one of the first “too big to fail” bailouts, which took place in 1984, when he allowed taxpayers’ money to backstop Continental Illinois, a failing bank.

Volcker’s career shows how a brilliant and deeply ethical public servant could set the stage for the unpopular Wall Street bailouts of our century. His genius also failed, in a way. The story illuminates the larger point that, ultimately, just as financiers themselves are both good and bad—constructive for growth when they allocate capital intelligently, and destructive when they make big mistakes and cause crashes—so the response to those people needs to be nuanced. If finance were just a morality tale, in which there were villains who need to be contained, the remedy for unstable finance would be extremely simple: tough regulation. That’s it. This is indeed the morality tale which I think some like to tell. But, in my view, it’s wrong.