“Revision”

FictionBy Daisy HildyardDecember 15, 2024Illustration by Klaus KremmerzThe awakening began for Gabriel in Oxford, in May, 2009. As final exams approached, everybody was talking about the girl who had walked up to the front desk of the social-sciences library and stabbed herself in the eyes with a pen. She survived, they said, but was permanently blind, and currently lying in the John Radcliffe infirmary, awaiting the arrival of her parents. There were rumors that students at Oriel College were being monitored through the bar codes on their library cards, but the story was spun in different ways. Some saw it as a dystopian conspiracy, with data being harvested for a eugenicist research project run by the head of the college. Others told it as a tale of the élite: the students who were found to be falling short would be quietly expelled so that the college could uphold its excellence in internal rankings.Read an interview with the author for the story behind the story.If these were extreme responses to the onset of the examination period, it was normal to do the things that Gabriel was doing: turning off his phone so that his family could not reach him; experimenting with cognitive enhancers acquired from the teen-age supplier who worked in the covered market; hiding in the college library at closing time so that he would be locked in to study overnight. On Sunday evening, two weeks before his first exam, Gabriel had not spoken to another human being for three full days. He was alone in his room, revising, when there was a knock at the door.Petra stood on the landing outside. She had come straight from the engineering building, and was still in her coat and backpack. It was past ten. She lifted two bottles of wheat beer, one in each hand, and asked, somewhat formally, whether he had time for a conversation.Gabriel let her in and went back to his desk. He didn’t close his laptop but returned to the paragraph he had been writing—half working, half listening—while Petra opened the beers and handed him one, then sat on the edge of his bed and kicked off her shoes.“Today, I spoke with my mother on the phone,” she said. “She told me how I can assume possession of the bars of gold in the bank vault if anything happens to her and my father.”Gabriel spun around on his chair. “Actual bars of gold?”Petra shrugged like a middle schooler. “We’re reducing our investments in them now—Pàpi thinks the value has to fall.”Gabriel slowly spun around again, and put his toe to the floor to stop when he was facing her. Petra was young—younger than Gabriel, although he was still an undergraduate and she nearly had her doctorate. She’d come to Oxford from Zurich at sixteen. Intellectually gifted. An only child. They were the two students who lived on this stairwell in the college’s central courtyard—neighbors, not friends. She was making herself at home, though, cross-legged on his bed, fingering a small stuffed Totoro toy, once white, now grubby and balding in patches, which she kept on a key ring attached to her belt loop.“Last weekend,” she said calmly, “a trespasser climbed over the walls and into the grounds at home. It was fortunate that the guards discovered him. He had a bread knife and a bicycle chain in his rucksack.”Podcast: The Writer’s VoiceListen to Daisy Hildyard read “Revision.”Gabriel made a low noise. He meant it to be sympathetic, but it sounded weirdly impressed. He understood now why Petra had knocked on his door. Her father, a banker, had been involved in an aggressive corporate takeover that had made him a public hate figure in Switzerland. There were death threats and silent phone calls; a panic room had been installed beneath the stables at the family mansion. Petra came to talk to Gabriel late in the evening, when she was possessed by fears for her parents. She never said this in so many words.She looked around the room, her eyes strained into a slight squint. It was an old space. Sloping ceilings held up by a huge, dark beam. A single bed. A desk and plastic office chair. Gabriel, tall and dirty-haired, a silver hoop in his ear.“You’re lucky,” Petra said.Gabriel thought of his own mother, alone in her small flat. He took a swallow of beer. “What were you doing in the lab today?”“I tested my module, of course.” Her tone suggested that it was ignorant of Gabriel not to know. “It’s going well, but we have hundreds of tests still to run.”“Sorry,” Gabriel said. “Can you remind me what the module does?”Petra’s squint intensified to a scowl. “It’s the size of a teakettle, and can be retrofitted to the engines of older cargo ships. Put simply, if it works as expected, then it will make an incremental difference to shipping-industry fuel use.”“And that has major value, right?”“Right—but only when we complete the tests, and then only if we can acquire a robust patent.”“Um. How does selling the patent work? Will the faculty make money from it? Will you?”“Sure.” She shrugged again, as though she did not really care to

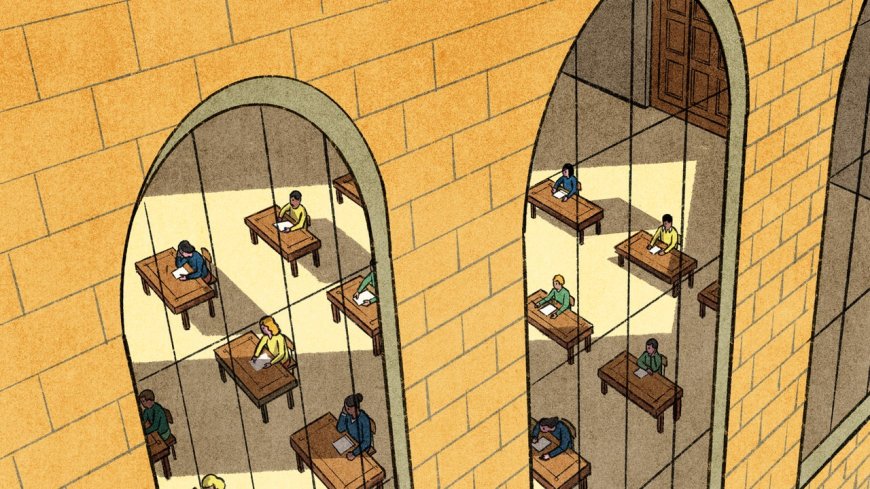

The awakening began for Gabriel in Oxford, in May, 2009. As final exams approached, everybody was talking about the girl who had walked up to the front desk of the social-sciences library and stabbed herself in the eyes with a pen. She survived, they said, but was permanently blind, and currently lying in the John Radcliffe infirmary, awaiting the arrival of her parents. There were rumors that students at Oriel College were being monitored through the bar codes on their library cards, but the story was spun in different ways. Some saw it as a dystopian conspiracy, with data being harvested for a eugenicist research project run by the head of the college. Others told it as a tale of the élite: the students who were found to be falling short would be quietly expelled so that the college could uphold its excellence in internal rankings.

If these were extreme responses to the onset of the examination period, it was normal to do the things that Gabriel was doing: turning off his phone so that his family could not reach him; experimenting with cognitive enhancers acquired from the teen-age supplier who worked in the covered market; hiding in the college library at closing time so that he would be locked in to study overnight. On Sunday evening, two weeks before his first exam, Gabriel had not spoken to another human being for three full days. He was alone in his room, revising, when there was a knock at the door.

Petra stood on the landing outside. She had come straight from the engineering building, and was still in her coat and backpack. It was past ten. She lifted two bottles of wheat beer, one in each hand, and asked, somewhat formally, whether he had time for a conversation.

Gabriel let her in and went back to his desk. He didn’t close his laptop but returned to the paragraph he had been writing—half working, half listening—while Petra opened the beers and handed him one, then sat on the edge of his bed and kicked off her shoes.

“Today, I spoke with my mother on the phone,” she said. “She told me how I can assume possession of the bars of gold in the bank vault if anything happens to her and my father.”

Gabriel spun around on his chair. “Actual bars of gold?”

Petra shrugged like a middle schooler. “We’re reducing our investments in them now—Pàpi thinks the value has to fall.”

Gabriel slowly spun around again, and put his toe to the floor to stop when he was facing her. Petra was young—younger than Gabriel, although he was still an undergraduate and she nearly had her doctorate. She’d come to Oxford from Zurich at sixteen. Intellectually gifted. An only child. They were the two students who lived on this stairwell in the college’s central courtyard—neighbors, not friends. She was making herself at home, though, cross-legged on his bed, fingering a small stuffed Totoro toy, once white, now grubby and balding in patches, which she kept on a key ring attached to her belt loop.

“Last weekend,” she said calmly, “a trespasser climbed over the walls and into the grounds at home. It was fortunate that the guards discovered him. He had a bread knife and a bicycle chain in his rucksack.”

Podcast: The Writer’s Voice

Listen to Daisy Hildyard read “Revision.”

Gabriel made a low noise. He meant it to be sympathetic, but it sounded weirdly impressed. He understood now why Petra had knocked on his door. Her father, a banker, had been involved in an aggressive corporate takeover that had made him a public hate figure in Switzerland. There were death threats and silent phone calls; a panic room had been installed beneath the stables at the family mansion. Petra came to talk to Gabriel late in the evening, when she was possessed by fears for her parents. She never said this in so many words.

She looked around the room, her eyes strained into a slight squint. It was an old space. Sloping ceilings held up by a huge, dark beam. A single bed. A desk and plastic office chair. Gabriel, tall and dirty-haired, a silver hoop in his ear.

“You’re lucky,” Petra said.

Gabriel thought of his own mother, alone in her small flat. He took a swallow of beer. “What were you doing in the lab today?”

“I tested my module, of course.” Her tone suggested that it was ignorant of Gabriel not to know. “It’s going well, but we have hundreds of tests still to run.”

“Sorry,” Gabriel said. “Can you remind me what the module does?”

Petra’s squint intensified to a scowl. “It’s the size of a teakettle, and can be retrofitted to the engines of older cargo ships. Put simply, if it works as expected, then it will make an incremental difference to shipping-industry fuel use.”

“And that has major value, right?”

“Right—but only when we complete the tests, and then only if we can acquire a robust patent.”

“Um. How does selling the patent work? Will the faculty make money from it? Will you?”

“Sure.” She shrugged again, as though she did not really care to know. “Both.”

It occurred to Gabriel to ask Petra why her father did not quit his post at the bank and allow his daughter to support him. She would be rich in her own right soon. Gabriel knew that this was not how wealth worked for the wealthy, that it was not a quantity but a scale. Still, from his position, he could see how easily the family could slip out of this labyrinth, with its gold bars, panic rooms, and gothic terror. His eyes went to his laptop screen.

Petra followed his gaze. “How is your revision going?”

“Fine,” he said. “Great.”

There was a long silence that didn’t seem to bother her. She drank deeply, then sighed comfortably, like a tired pet, and settled her back against the wall.

“Actually, it’s a disaster,” he said. “I know I’m close to doing well, but I have this one paper on medieval literature that I just don’t get. I can’t get a first if I don’t do well in that paper.”

Petra frowned. “So learn the material.”

“Hmm. Yeah. It’s, like, not only the texts I have to learn. There’s a whole history behind them that I don’t know the way the other students know it. It’s already too late for me to learn that. They knew it before they came here.”

Petra looked blankly at him. “Gabriel, history is just facts. You don’t have experiments or computations.”

He gave it up. “Yeah, O.K. Yeah, I guess.”

“You should talk to your tutor about this.”

Her international-school accent, Euro-American, had a parodic quality—it was sometimes hard to take her seriously. When Gabriel’s actual friends joked about his off-the-map relationship with his oddball neighbor, he responded by smiling, shaking his head, and firmly saying no, they were not sleeping together. In fact, he did not find Petra attractive. Her cheeks were always damp—a slick moisturizer, or perhaps her acne was weeping. He didn’t feel sorry for her, either—solitude and fearfulness did not qualify a person for pity in this place. Keeping her company was, rather, a kind of tolerance that he had discovered in himself. Now he was tired, and the essay he had been working on was basically done. He pushed his beer away and said plainly, “I have a tutorial in the morning. We should get some sleep.” Petra left, neither offended nor apologetic.

In the morning, Gabriel arrived punctually for his tutorial, tapped on his supervisor’s door, and waited. It was quiet. The latticed window beside him was open, drawing a breeze down the stone spiral staircase, and Gabriel pushed the pane wide to lean out. He emerged, head and shoulders, into a clearing within the wisteria and roses that grew thickly over the front of the building. Below him, in the courtyard, a gardener wearing a straw hat and a long skirt was spraying and snipping at the climbers. The breeze gusted, each stalk lifted and swaying, and Gabriel was ambushed by a feeling of sufficiency. He decided that he would say something to his tutor after all. Then a male voice called him in.

Thornton was sitting at his desk in his small study, surrounded by bookshelves, with a book open before him. He looked up and greeted Gabriel, and then looked down at his book again.

Gabriel stood awkwardly between the door and the back of a sofa, facing Thornton, and his calm drained away. His tutor was completely absorbed, slight and otherworldly in his raincoat and hiking boots, as though he were about to set off for a mountain peak. Gabriel shifted from foot to foot. He cleared his throat.

“Dr. Thornton, I need you to help me. The Middle English examination will bring down my mark, and the grade is forever. My future is at stake.”

“Well,” Thornton said. He blew gently on the dried glue that had broken off of the cracked spine of his old book; it scattered across the desk. Then he closed the book and turned to look at Gabriel. His gaze shifted from Gabriel’s flushed face to the faded T-shirt, then the clenched fists. “So, Gabriel, the concern is that you’re doing better in the other papers than you are in here, with me?” He spoke lightly, merely trying to elucidate his student’s point.

Gabriel shrugged miserably and turned his face away. “I’ve studied Middle English for two years now, and I still don’t actually know what it is.”

Thornton raised his eyebrows.

Gabriel was conscious that he looked sullen. He fixed his eyes on the spines on the bookshelf. “I don’t have the grounding in English history that everybody else has. Most of them took A-Level History, I get that, but it’s not only that. It’s like they belong to English history, and it belongs to them. For this paper, with you, I just don’t know about the Middle Ages, and so I can’t write the essays.”

Gabriel halted, blushing deeply. He was still standing in the narrow space between the door and the sofa, his body stupidly tensed. Thornton was listening with a serious look on his face. Gabriel resolved to see this through.

“It’s as though everybody else here grew up in a place I’ve never visited,” Gabriel said. “The other students actually laugh when I get the kings and queens confused, even though there are so many queens of England called Elizabeth, not just the ones who were actually Queen Elizabeth, and there are eleven kings called Edward. Eleven. I have to compete here with people like Charlie, who literally went to school with the royals. We’d be on a different footing if we were all assessed on, like, the families of Matt or Khadija from my physics class at Harrop Fell.”

A certain relief passed through Gabriel at having unburdened himself, but it went away when he glanced at Thornton, the only person in the world who could help him now. The chances were remote. Thornton, in his chair, one matchstick leg crossed over another, could not have looked more like a classic Oxford case: thoroughly adapted to his environment and useless elsewhere. Friendly but evasive, Thornton couldn’t make eye contact, he did not have a driver’s license, and it was not at all unusual to spend a tutorial engaged in a search for a possession of his—perhaps a coffee cup, perhaps a favored pen—that had peregrinated to the back of a bookshelf, or to a sunny flower bed beside a bench in the front quad. He was not much older than Gabriel—one of the many academics here who had arrived as an undergraduate and simply never left. It was reasonable to assume that Thornton would have been a failure had the institution not existed to render him miraculously élite.

Thornton was waiting now, apparently to establish that Gabriel’s speech was over. When he was sure, he spoke. “Harrop Fell?”

“It’s the name of my school.”

Thornton nodded. “Well. I’ve never had a student put it quite so. But all your papers require context, Gabriel, even the modern ones. And everybody lives in history, of course.”

He made a low-pitched, thoughtful noise, as though something mildly interesting had occurred to him, and caught Gabriel’s gaze. There was a charge, a beat—something jumped between them that surprised them both. Gabriel looked down to the floor, and Thornton’s gaze skated away. He gave a small, feminine sigh.

“Ah, well. Gabriel. There’s a lot here. But I can help you only with this one thing: the class of your degree.”

Thornton stood abruptly, and then seemed to lose his train of thought. He leaned over his desk with his back to Gabriel, sifting through books and papers; a miasma of dust and glue scatterings rose from the pages as he unsettled them.

“Do you have your Chaucer with you?” he asked.

He turned and blinked compulsively. There was a pause, and then he closed his eyes and spoke more rapidly, in a raised voice, as if he were trying to make himself heard over background noise. “There is a quote, Patterson on Chaucer’s ‘Troilus and Criseyde.’ I think it goes something like this: ‘The poem’s deepest message is about the failure of history, and of historical understanding, per se.’ You can work on this as an essay question. If you write on that, you’ll be able to examine these issues which are troubling you.” Another brief, broken pause. The conversation snapped open.

“I am willing to give you extra tutorials during these next two weeks,” Thornton said. He did not sound as if he was conferring a favor—more like he was making a plea. “You could do timed essays on the sofa . . . while I am at my desk at work?”

Gabriel nodded and agreed. He asked for the Patterson reference, and Thornton hunted for the book and then for the page, which took some time; the room’s charged energy relaxed. At the end of the tutorial, as Gabriel was leaving, Thornton asked him to wait. “Close the door.”

Gabriel did as he was told.

“Don’t—whatever you do,” Thornton said, “don’t try to cheat.”

“Oh,” Gabriel responded, smiling and shaking his head. “No, I hadn’t thought about that, no.”

“It won’t work.”

Gabriel shook his head again and left.

After closing the door behind him, he stood still on the stairwell landing. It was a crazy idea that hadn’t come across his mind at all. He looked down: his feet in scuffed Adidas on the flagstone, where centuries of students, ascending and descending, had become a force of erosion. Light and air filtered through the window, through the rose and wisteria leaves, and Gabriel’s seamless sequence of thoughts culminated with the beautiful clarity of a solution, which was that he could cheat.

Gabriel had attended a normal school, wore sportswear, and had male friends from home who got into physical fights when they went out on a Saturday night. His peers at Oxford therefore believed him to be “street,” a word that was spoken ironically but found useful as a marker of class and relative cachet. The undergraduate students here were more likely to have spent time in Brooklyn, Roppongi, or Kreuzberg than to know what happened in the windowless corridors of an English provincial state school, and Gabriel did not awaken his peers to the leafy, left-leaning serenity in which he had grown up—an area of Manchester populated by young families, old hippies, and recent immigrants, whose citizens distributed their time among allotments, community arts centers, madrassa, and piano lessons—a gentle, open, roughly friendly place where people joked that the only common language was lentil dal.

Gabriel felt that his reticence was fair. He had never been coached or shown the way; his high school was failing while he was there; his mother was chronically unwell, living on disability benefits. At school, Gabriel had been exceptional because he looked like the kind of kid who might get into Oxbridge. When he arrived in Oxford, he became exceptional because he did not at all look like the other young people who had made it here.

This new experience of difference was, initially, rewarding. Gabriel had more sex than ever before. Boarding-school girls were drawn to him, and he was impressed by the harsh power that they exercised over themselves: their pretty, managed forms, their silky locks of hair, their bodies, which had been tailored by regular participation in team sports, in short and tight dresses. Even their personalities had been worked over, to the extent that the nights eerily repeated themselves. Perched on a barstool, playing with her hair, whichever girl he was with would be brutally disparaging about herself, and so quick to laugh at the things Gabriel said that he doubted she had actually heard his words. Then the morning after, disarranged, she would be grumpy and unexpectedly cutting, impatient for him to leave.

Eventually, his fascination with these girls diminished. The seasonal-affective-disorder lamps, the requests to be slapped during sex, the amaranth salads in brown cardboard boxes, like gifts—all these things assimilated themselves until they became ordinary elements of Gabriel’s world. He acquired a subtle pity for the students, male or female, who had attended these segregated, expensive, isolated schools. They bore no resemblance to the debauched caricature of the Oxford student that was depicted in novels and newspapers. Instead, they brought to mind the neurotic zoo animal who has been driven to dementia by its reduced, serviced universe. There was a nervous, pacing energy to the way in which they relentlessly monitored and evaluated others while remaining on their guard, permanently hyperconscious of their own subjection to reciprocal surveillance.

Then Gabriel reached the revision period, right at the end of his degree, and his sympathy abruptly flipped. These people, who came here not through merit but as birthright, were lazier than he was and, objectively speaking, more stupid. Yet they were poised to crush him, in the final examinations and then in real life. Decades from now, they would be making the money, ruling the country, running the news, and writing the history. Gabriel did not wish to become an overworked, underpaid secondary-school teacher. He needed a first-class degree.

When he came out of his session with Thornton, he went to look for June. June would help. June, Gabriel’s tutorial partner, teased him for hate-fucking posh girls who believed he was rough. She had a tiny spike in the top of her ear and spent her days in the library reading, and she was in her element now, as exams approached. She knew what she was doing. The first time they had met, in a bar at the start of the first term, Gabriel had begun to talk to June about his latest date, and June had informed him, earnestly and with a genuine sense of apology, that, sorry, the conversation was not very interesting, from her side. She made Gabriel feel unsure of himself, but he did not feel watched by her. He didn’t feel that she was looking at him, that much, at all.

Gabriel walked around the college, searching for June in the library, and then the common room, and then the canteen, and she was there, sitting alone at a long-top table with a paper cup of coffee, a library book, and an unopened packet of chocolate biscuits. Gabriel sat wordlessly beside her. June closed the book, opened the biscuits, and offered them to him; he took one and placed it on the table in front of him. She tapped the book cover, on which there was an image of James Joyce leaning on his cane. “Why do all the male critics lose their minds about the fact that Molly’s speech gives voice to the common woman, when in fact she is an avatar of Joyce’s barely literate wife, scripted by Joyce?”

This was not exactly a question. June spoke quietly and thoughtfully, staring out into the vacant dining hall before them, then looked sideways—seemingly registering Gabriel’s presence for the first time—and shook her head. “Never mind. You won’t get it.”

Gabriel picked up the biscuit and ate it slowly so that he did not need to reply. June often acted as if he had no sense of politics or identity or the bitter reality beyond the college walls, to which the undergraduates occasionally, with vague reverence, referred. In tutorials, she spoke over and around him, addressing their supervisor directly whenever matters of race, class, or gender, politics or justice, arose—which they did, when June was speaking. The punch line was that June herself had gone to private school. This joke was one that Gabriel had heard on repeat through the past three years, and it didn’t make him laugh anymore.

Gabriel had lost track of the conversation, which was more of a monologue now. June’s voice seemed louder than usual. “You have to answer the question that is written on the exam paper,” she was saying. “That sounds obvious, but it’s harder than you’d think to pay attention to the question and really see it, respond to what it actually says and not what you want it to say. Most people just write out what they have revised and squeeze the question to fit.” She made a quick, startling motion with her hands. “You won’t get a first if you say what everyone else is saying. It’s like you have to say the wrong thing in the right way. Not the right thing in the right way—that’s just box-ticking—and not the wrong-way right, what even is that? And the wrong-way wrong is too far. The examiner won’t understand what you are talking about.” She giggled. “It has to be the right-way wrong.” She nodded to herself and turned to look at Gabriel almost pleadingly, inspired and daunted by her own vision.

“Do you know,” he asked in a deliberate and casual tone, “whether they search us when we go in? Our bodies, I mean.”

“Pat us down?” June giggled again. “They could try. It might make the Times.” She shook her head. “No, Gabriel. I don’t think they’re very interested—you can go to the toilet during the exam, and they don’t even walk you down the corridor. It’s a gentlemanly understanding. Why, are you planning to cheat?”

Gabriel put his arm over the back of his chair and smiled. “Yeah, I thought I’d write all the dates for the Middle English paper on my legs.”

“Nice.” June narrowed her eyes. “I guess there would be a fairness to that, like a handicap or a head start.” She pressed her lips together. She was either suppressing irritation or on the brink of laughter. “You’re cleverer than the rest of us, but you don’t know fuck all about the past.”

“Your voice is loud,” Gabriel said, screwing up his eyes. “Are you taking caffeine pills?”

June placed her palms down on her closed book, a devotional gesture. She didn’t seem to be conscious of it. “Gabriel, we’re worried about you,” she said, lowering her voice. “Ruby and Charlie and me. Just don’t do something fucking stupid like the social-science girl.”

“Oh,” Gabriel said. He smiled and shook his head. “No, I wasn’t planning to. No.”

The next day, in the afternoon, Gabriel returned to Thornton’s office. Thornton gave him paper, a board to rest on his knees, and a question to answer. Gabriel sat on the sofa while Thornton, his back to Gabriel, worked at his desk. He put on a Mahler CD at a low volume, and this softened the space between them so that they did not feel quite so alone together.

At the end of the hour, Gabriel read aloud what he had written, and Thornton listened intently, then briskly explained what could be interesting about Gabriel’s thinking; the mistakes and omissions he had made; and what he needed to read. After the session, Gabriel went to the library to find the recommended books, leaving his essay with Thornton.

He did the same thing the next day, and the next. Thornton did not annotate and return his scripts, which prompted Gabriel to realize that he would have to pay closer attention to the conversation as it happened.

This changed something. Gabriel felt present in that room in a way he hadn’t felt for months. The window was usually propped open, and, when the music was off, the buzz of distant traffic and a fitful breeze entered. Gabriel almost enjoyed listening to the thorny, vowel-dense sounds of the Middle English texts when Thornton read from them in his prosaic manner, and he came to appreciate the casual knowledge of old things that Thornton let fall into the conversation, as when he told Gabriel that Chaucer’s favorite flower was the ordinary daisy, or that it took eight calves to make a slim book on vellum.

On the seventh day, the essay title was taken from Chaucer’s translation of Boethius: “ ‘Where wonen now be bones of trewe fabricius? What is now brutus or stiern Caton?’ Consider relationships of influence or difference between Old English literature and Middle English writing.”

The quotation was enigmatic to Gabriel, but the question felt aggressive, as though it had been designed with the intention to silence any student who had never been tutored on the respective circumstances of Old and Middle English—and it had. Gabriel was muted.

He sat still with the board and blank paper on his knees, struggling with a sense of proportion. Terrible things were happening in the world. Sweatshops and roadside bombs. People were living in deep poverty right there in Oxford, on the ring road and in the outer suburbs, beyond the university. This test in front of him was just an old exam paper with a question about the long-gone past. Yet this precise knowledge, these exact facts, had receded into its own meaning, which had acquired a weight that Gabriel could neither bear nor relinquish, because knowing this material was critical to his future and he did not get it. The meaning he could not quite grasp, just out of his reach, beyond the tip of his tongue, could not stand in contrast with the terror of the world because it was, in some way Gabriel could not get straight in his head, intrinsic to it.

Thornton cleared his throat, and politely interpolated his thoughts. “I can see that you are not making progress. Shall we break this down?”

He turned off the music and ran through a sequence of modest and manageable ideas—ideas that Gabriel could cope with. Thornton wrote down dates, names, a battle. He reminded Gabriel of the passages in Old English poetry in which heroes of the past list their immense losses and reflect on how inane and hopeless worldly achievement is.

“You will remember the Seafarer’s loneliness,” he told Gabriel with perfect confidence, “and the passages in which the Wanderer asks where his universe has gone. His horse. Parties. Money and friends.” Thornton opened his empty mouth like a goldfish, articulating an almost silent pouf.

Quiet again. Through the open window, Gabriel could hear a distant sound of drilling. He felt the bubble of emptiness that Thornton had emitted inflating, filling the room, and swelling into the surrounding area. His eyes began to sting, betraying him. He knew that Thornton would correctly identify self-pity.

But Thornton showed no sign of scorn or even embarrassment. Instead, he said something that did not make sense to Gabriel at first: “I don’t think I have told you that we went to the same school.”

Gabriel’s mind went to the physics laboratory at his secondary school, as though he would immediately, miraculously retrieve a memory of a teen-age Thornton sitting at one of the long counters in his hiking boots. But the room was vacant, and only then did it make sense—Thornton was saying that he had been a pupil there some years before Gabriel arrived. Gabriel did not know how to respond.

“You don’t sound like you’re from Manchester,” he said at last.

“Quite.” Thornton looked at Gabriel levelly and held his gaze. “Nevertheless. I do understand what it is like to be a working-class undergraduate here. I can tell you, the situation has improved since my time. Back then, we had to cover our tracks.”

Gabriel had not thought of himself as working class before. It was too exposing and direct a term, too confrontational for his peers to apply. It made him uncomfortable, though he did not know why: whether the idea of the lower class or the possibility that he was not, in truth, lower class at all was the authentic shame. He was aware that he wasn’t alone in that. Many of his peers felt that they were outsiders in this place. Perhaps there were more people outside than in.

He played five-a-side football with a second-year named Adam, who’d confided to Gabriel the pain he felt “as a state-school kid” when tutors, administrators, and even his closest friends repeatedly mispronounced or Anglicized the spelling of his Polish surname.

In the English department, Gabriel took seminars with Chantal, who had told him that she avoided social events because of trauma she had inherited from her mother, who had grown up in rural Vietnam in the nineteen-sixties.

Once, in his first year, Gabriel had been at the college bar with Robert, who lived next door to him. A group of male students from another college came into the bar, and greeted Robert as an old friend. When they left, Robert told Gabriel that these boys had bullied him for a decade at boarding school, where he was the scholarship boy. Now, here, they were still tormenting him with feigned friendliness—“Roberto, mate”—as though their past were a shared joke.

But Gabriel had alternative intelligence on Robert and Chantal and Adam. A knowledge of everybody’s background was part of the infrastructure of undergraduate social life. Adam’s mother was an author and psychoanalyst whose practice was based in Hollywood. His state school was in a London neighborhood where the average house price topped a million, and it sent more students to Oxford and Cambridge than entire cities in the North.

Gabriel had heard Chantal speak of her mother’s trauma several times, but he had never heard her mention that her father was a diplomat and had a private jet.

Robert was somebody whom Gabriel knew better, and one night in the pub Gabriel pressed him on the question of money. Robert, evidently uneasy, told him that he believed his scholarship was honorific, worth two hundred pounds, and that the annual school fees . . . he was not sure . . . were perhaps forty thousand.

Gabriel understood that the pain his friends had described was true for them, and that the suffering they experienced—intergenerational trauma, or bullying, or the simple, significant disrespect of having their name repeatedly mispronounced—was real. This did not prevent him from thinking of his friends as liars, and articulating that word to himself offered an ugly but undeniable relief. Liars. And there he was, too, a straight white man and a raw hypocrite. Surely somebody was on the inside, holding power, and yet everybody here felt iced out, their privilege and their victimhood irreducible against one another; each personal combination private, hurtful, and too tender to touch.

Gabriel looked at the man sitting opposite him, who presented as a boarding-school boy, oddly aged, but was actually working class. Thornton was eying his student carefully, with concern or interest.

“Well,” he said, finally. “What matters for you now is to be sensible. Eat good food, sleep wholesome sleeps. Don’t do anything drastic, and you shall do well.” He was in teaching mode again. “Gabriel,” he said gently, “our tutorial has finished.”

The night before the first exam, Gabriel was already in bed, watching an old episode of “Seven Up!” on his laptop, when there was a knock at the door. It was Petra, in pajamas and a fleecy dressing gown, her wet hair hanging in long strings and an expression of extreme distress on her face. The assailant must have found his way in, at last. Perhaps her parents were injured, or worse. Gabriel allowed the door to swing open and stepped aside. Petra floated past him and sat on the chair at his desk.

“My father’s bank’s gone bust,” she said baldly.

Gabriel closed the door and leaned his back against it.

“He’s lost everything he’s made,” Petra said in the same abrupt, almost belligerent tone. “We have to sell the house, and the gold, and it still won’t be sufficient to pay.”

There was a moment’s silence. Petra sniffed, and Gabriel looked around for a tissue, then wondered whether he should leave the room to retrieve one from the bathroom across the landing. He decided against it. She wiped her face with her sleeve. “What happened?” he asked.

“It’s the same as Lehman. The same as all the others. That world is over.” She drew an empty circle in the air. “The money was borrowed from funds that weren’t there.”

“He’s safe, though?” Gabriel asked.

“Sure.” Petra made a dismissive gesture. “But, Gabriel,” she said reprovingly, “my mother says there’s nothing. My father will be fortunate if the shareholders don’t pursue him through the courts. . . . His world is over,” she repeated. She sounded distantly awed by what she was saying: not yet quite awake in this revised reality. “He could go to prison—”

Gabriel did not realize he was about to yawn until it happened. It cut a hole in the conversation. Petra stopped talking.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

Petra stared at him. “You are a friend to me,” she asserted in a harsh voice.

They were quiet.

Eventually, Gabriel spoke. “Do you want to stay here for now? I was watching a show. We could watch the rest together.”

Petra nodded.

“Petra, I think your family will be fine.”

They sat on the floor and watched to the end of the episode. When it was over, Petra asked to stay in Gabriel’s room.

Gabriel looked at the clock: past midnight. His examination would be later that morning. “O.K.,” he said slowly, thinking it over. “You can have the bed.”

Gabriel changed into his pajamas in the bathroom, then took one pillow and lay down on the floor under the window. The floor was hard, and he felt chaste and purified by his offer to sleep there. Hours passed. He could hear Petra breathing through her mouth. He stared up at the ceiling, watching the light change on each of its slopes, and avoided looking at the clock’s face.

When Gabriel arrived outside the examination school in the morning, he felt weird. He stood on the pavement, swallowing scalding coffee from a wilting paper cup. Thornton appeared, crossing the road from the college, his approach slowed by a very small, dark-haired child who was holding his hand. Gabriel shook his head and blinked.

“Dr. Thornton!” June cried. “I didn’t know you had a kid!”

Thornton fixed his eyes to the wall behind June’s head with a comical, quizzical look. “Let’s hope you were paying more attention when we discussed the texts.” He sounded jocular. “This is my daughter, Raine.”

Gabriel greeted them, then turned his back, swallowing the last of his coffee. He faced the imposing building. Tall windows, a columned portico, and sculpted reliefs depicting university patriarchs. Façades and colleges extended up the road, all the way to the statue of a notorious colonialist that stood in a stone recess, surrounded by a twisted and petrified decorative frame.

A friend of Gabriel’s had complained about this statue, suggesting that the college should take it down. A warden had responded that it was held in place to commemorate the iniquities of history. That morning, on the day of his exam, looking up at the stone façades, Gabriel suddenly realized that this was a place that existed not despite but because of the iniquitous history exhibited here. Oxford, no longer relevant to the contemporary world in so many ways, was advertising its special connection with the cruelty and suffering that had been rolled out across the entire planet, over centuries, and still rolling away. Gabriel’s eyes rested on the mosses and lichens that had grown over the old stone building, and he had a short-lived, beating impression that their huddled forms, augmented by morning shadows, had mobilized and were edging toward him. Then he turned around, and Thornton was wishing everybody good luck. The doors opened.

Inside the exam hall, a big room with long windows, full of quiet, Gabriel felt unfettered. Elated by exhaustion, he became expansive. He felt lucky. It occurred to him that an ordinary seminar room—low-ceilinged, with carpet squares and a whiteboard at the front—would not have had the same physical capacity to hold and refresh ideas as this high-ceilinged, pillared, airy space. He found his chair and sat down, conscious that it was an extremity of privilege to be examined here. For the first time, he accepted that this privilege was in his possession. He had taken his place at the table.

He held still and closed his eyes. His mind jumped around. Dates and quotations were unreachable, every fact revised. His mind zoomed out, and he had a vision of a great complex. It was a bit much, like being shown a hidden camera that had been tracking beside him all along. The ingredients of his luck: The stone slavers who stood outdoors, and the sugar and cocoa that were baked into June’s packaged biscuits. The gardener’s insecticide that killed the aphids on the roses, releasing the old, rich, scented breeze that had infected him with self-confidence. Petra’s father’s collapsed bank. The bones of knackered cattle in the glue that held his antique books together. His clever mother’s missed opportunities. The scarred hands of the miners who extracted the coltan and cobalt that now resided in his silenced phone. The web of shipping channels that bound it all. The well-stocked libraries; many long hours of Thornton’s time; and years, rooms, and space in which to learn, all produced on the backs of the past. Eight calves.

He felt relieved of something, actually—he’d dropped the thread running through the labyrinth, and that was fine, nobody gets out. The line wasn’t working anymore. It was good that he hadn’t tried to cheat. What mattered now was to submit his experience to the clean sheet of paper on the table. The monitor called out the instructions, and the exam papers, swishing open at the same time, created a pulse of air. Gabriel relaxed, allowing himself a few moments to read the questions, choose one, and consider it.

Something strange twanged in him on the first question. It was a quote from a secondary source: “For the poem’s deepest message is not about the failure of any particular historical moment but about the failure of history, and of historical understanding, per se.” The second question had a passage from Chaucer’s Boethius, which Gabriel already knew by heart: “Where wonen now be bones of trewe fabricius . . .” He had seen the next question, too.

He scanned the page in a panic. He had answered all of these questions. Thornton had placed each one before him last week and the week before. The questions on this sheet were identical to those of last year’s exam paper. He started to put up his hand, hoping that there had been a simple mistake. The correct paper could be brought to him, and he would be compensated for the lost time. And then, before his arm had reached its height, the understanding came that this was not last year’s exam.

His hand was still in the air, and the monitor was walking toward him. Gabriel put it down and shook his head, and she retreated. He felt an obscure sense of shame, a deep disgust with himself that he could not force into sense—as though he had turned up to a blind date and found his mother waiting.

He looked down at his paper. He looked up, around the room. The other students had a faint, anxious appearance, their differing characters had receded deep inside their bodies for the duration of the examination. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary to them. They were required to respond to three questions, selected from eleven. Gabriel could tolerate this. He already knew that he would not tell anybody what Thornton had given him. His tutor’s intention had been to rebalance his chances, and, anyway, there was no evidence.

Now, there were two options that had integrity. The first: he had an advantage, and so he must excel by the same distance. Rather than responding to three questions, as was required, he would respond to every single one. He could absolutely do that. The second possibility was that he could stab his pen into his eyes. His hand began writing without planning or thinking, and the material arrived from somewhere behind conscious thought. He wrote desperately. When he requested more paper, the woman brought it to him, and he received it without thanking her. The hours streamed past until he had written eight essays, all continuous with one another, and he knew that he had achieved something exceptional when the monitor called time.

One week later, the English-literature students left their last examination, exiting through the back of the building into a cobbled lane. June blinked in the light and felt the tense awareness that had been with her throughout the examination period diffuse into the environment. It was a cool, gray morning in late May. Branches of mock orange extended over the walls of the college gardens, dropping loose white blossoms, their released scent weakened by the chill of the air. Somebody handed her a water balloon. She held it cautiously and walked on, not yet in the mood to deploy it.

Gabriel appeared in the crowd and fell into step beside her.

“There you are,” he said.

He lowered his voice and said that he’d wanted to talk to her, and then went on to say, in his sudden, awkward, halting way, that he had made a serious mistake in one of his papers. His case had already gone to review. He hadn’t followed the most basic instructions, and the university board had judged the paper to have been disqualified. He could still hope for a second-class degree, he explained, if he achieved high marks in his other papers. He shrugged and smiled lopsidedly. He’d never wanted to be a banker or politician, anyway—he’d be more useful as a history teacher and had downloaded an application to train.

June let the water balloon fall into the gutter and put her arm around Gabriel. “I’m sorry,” she said.

She did feel sorry for him, and somehow bewildered: she could not understand why he had done this the wrong-way wrong. If he were a woman, she told herself, he wouldn’t assume the world would be so friendly to his experiments.

James Thornton was standing in his office, looking out the window, when the students emerged from the lane onto High Street. He felt a current of strong irritation when he caught sight of them, crowding around one another in the middle of the road, covered in flour and food dye. They were all still so immature, and yet they were also real and indisputably adults, just as much as he had been at their age, though he had had more responsibilities then than these kids could imagine. Their rounded faces, their piercings and makeup, their lateness and absences and profuse, careless apologies—their vulnerability was almost intolerable. Tears would spring to their eyes if he made a sharp comment about their use of quotations in a weekly essay. Each time they came to his office, they would confide to him whatever terror, longing, humiliation, or desperate desire they possessed, then walk out of the tutorial and forget that he existed, until next time. He was perpetually amazed and a little impressed by this entitlement. Even the most considerate of them were innocent of the fact that anything they took from him had been, and had to be, extracted from another part of his life: Raine or his girlfriend, Mae, his delayed monograph, his untidy home, his tired body. He had given to them freely—Mae believed excessively—because he cared for them. And now he was ashamed of himself, too, because he was distraught that they were leaving, though he wanted them to go. He could not talk about this, even or especially to Mae. They were not leaving him—they were just leaving.

In the college courtyard, after the people had all gone home for the day, the roses remained, still growing at their own stately pace. They were dependent on the earth in the flower beds and the wiring on the warmed stone walls, and absolutely indifferent to the fates of individual students. The gardener’s recent spray had liberated them from the aphids that had been bothering them for weeks, and now they were free to open. The stems moved so slowly that the people around them could not discern the movement. Nevertheless, every single one was animate, and aspiring upward, where it was slightly warmer and there was a little more light. ♦