“Paradise” Is Manna for the Moment

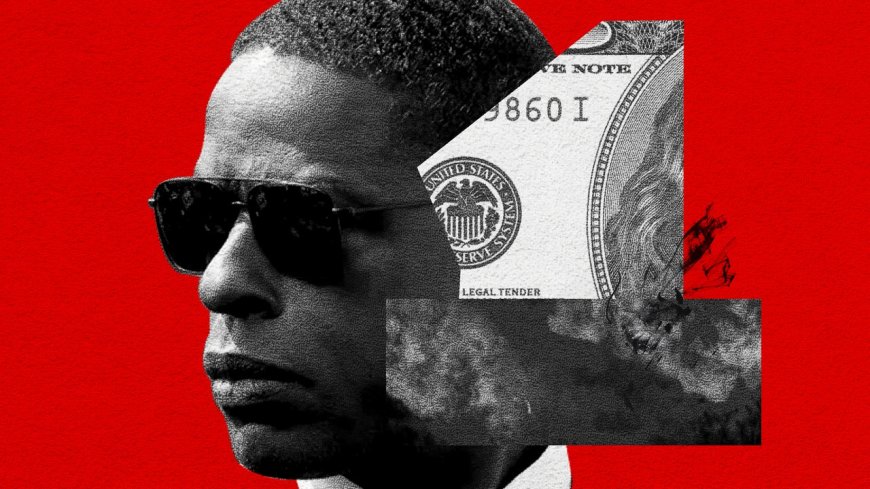

Critic’s NotebookThe clanking didacticism of Dan Fogelman’s new Hulu series, which involves climate disaster, nuclear war, and the insurgency of the billionaire class in politics, is deeply satisfying.By Doreen St. FélixMarch 1, 2025Illustration by Nicholas Konrad; Source photographs from Getty and Hulu“Paradise,” on Hulu, is a political thriller with a vintage feel. Surely Hollywood’s obsession with the Presidency has produced this kind of drama before? There is the handsome white Commander-in-Chief, President Cal Bradford (James Marsden), shuttled to the high office through the maneuvers of his emotionally abusive baron of a father. And there is his Black sentinel, Agent Xavier Collins (Sterling K. Brown), a smileless Secret Service officer—the other half of the show’s “Driving Miss Daisy” main coupling. Agent Collins’s inexhaustible fidelity to the President, and therefore to the nation—a fidelity that will lead to him taking a bullet meant for his white ward—makes his dignified father, a former Tuskegee Airman, so proud that the normally unflappable elder Collins loses his composure. These characters are familiar. And yet “Paradise” uses its retrograde premise to its advantage. This is not at all a surprise, considering that the creator is Dan Fogelman, the writer and director who had a vise grip on network television in the twenty-tens with “This Is Us,” a series that my colleague Emily Nussbaum memorably called a “family weepie.” “Paradise,” Fogelman’s latest project, is meaner and leaner. The structure of the family is secondary in importance to the structure of power and governance.The first few minutes of the pilot train us on the rituals of Agent Collins, a sad, disciplined man. We see that sleep doesn’t come easily to him; the other side of the bed is empty. His children, a teen-aged daughter and a younger son, feel his melancholy, and try not to destabilize him too much. They live in suburbia, the eponymous “Paradise.”Collins, the lead agent for President Bradford’s security detail, heads into work. But he doesn’t go to the White House; rather, we watch him enter a beige mansion, within walking distance of his own home. There he finds the President, who is lying on the floor of his bedroom, lifeless, in a pool of blood. Though this event—the President’s apparent murder—might seem like the episode’s big twist, the true reveal comes later, as the pilot self-seriously unravels what is so off about our so-called Paradise. It turns out that a massive climate event made the world untenable. “Paradise” is actually a bunker, a simulacrum of society, constructed underneath a mountain in Colorado by a cabal of billionaires. Humanity has been reduced to twenty-five thousand people.The twist is manna for the moment. The rapacity of Elon Musk, who has seen his plan to hijack the government come to fruition, is a clear inspiration for the drama. The show’s clanking didacticism is deeply satisfying: the plot salad involves climate disaster, nuclear war, and, perhaps most acutely, the insurgency of the billionaire class in politics. Flashbacks show how the old-money Bradford came to become President of the United States, and then President of the bunker, which is to say, nothing more than a puppet nursing a drinking problem in a tree-lined underworld. Julianne Nicholson plays Samantha Redmond, an app developer who prides herself on being the “richest self-made woman in the world.” She has been hardened by the loss of her son, who died, years before the apocalypse, from some mysterious illness. On his deathbed, the boy had asked his mother what heaven would be like. “The thing about heaven, it’s anything you want it to be,” she responded. He imagined a place stacked with coin-operated horse rides. And so Paradise, which would ultimately be constructed by Redmond and her allies, has a symbolic toy horse. Back aboveground, an angry scientist, a kind of prophet character, had grabbed the attention of Redmond, who conspired alongside Bradford and a horde of undifferentiated billionaires to create a bunker in anticipation of catastrophe. In the bunker, Redmond becomes the ringleader; her Secret Service code name is Sinatra.“Paradise” is about grief and lies. In the Before Times, Sinatra, debilitated by her son’s death, had sought out the assistance of a world-class therapist, Dr. Gabriela Torabi, played by Sarah Shahi. In the bunker, Dr. Torabi confides to Collins about her role in the construction of Paradise, confessing that she personally selected each member of the manufactured society, meaning that she also decided who would get left behind. (“Paradise,” only eight episodes long, off-loads a lot of exposition to its characters.) Other great minds willingly contributed their expertise to the success of the project. The message is bleak. People of means, and people of science, will privilege their own survival in the event of total societal collapse, and they will feel that the decision is justified, even moral. I

“Paradise,” on Hulu, is a political thriller with a vintage feel. Surely Hollywood’s obsession with the Presidency has produced this kind of drama before? There is the handsome white Commander-in-Chief, President Cal Bradford (James Marsden), shuttled to the high office through the maneuvers of his emotionally abusive baron of a father. And there is his Black sentinel, Agent Xavier Collins (Sterling K. Brown), a smileless Secret Service officer—the other half of the show’s “Driving Miss Daisy” main coupling. Agent Collins’s inexhaustible fidelity to the President, and therefore to the nation—a fidelity that will lead to him taking a bullet meant for his white ward—makes his dignified father, a former Tuskegee Airman, so proud that the normally unflappable elder Collins loses his composure. These characters are familiar. And yet “Paradise” uses its retrograde premise to its advantage. This is not at all a surprise, considering that the creator is Dan Fogelman, the writer and director who had a vise grip on network television in the twenty-tens with “This Is Us,” a series that my colleague Emily Nussbaum memorably called a “family weepie.” “Paradise,” Fogelman’s latest project, is meaner and leaner. The structure of the family is secondary in importance to the structure of power and governance.

The first few minutes of the pilot train us on the rituals of Agent Collins, a sad, disciplined man. We see that sleep doesn’t come easily to him; the other side of the bed is empty. His children, a teen-aged daughter and a younger son, feel his melancholy, and try not to destabilize him too much. They live in suburbia, the eponymous “Paradise.”

Collins, the lead agent for President Bradford’s security detail, heads into work. But he doesn’t go to the White House; rather, we watch him enter a beige mansion, within walking distance of his own home. There he finds the President, who is lying on the floor of his bedroom, lifeless, in a pool of blood. Though this event—the President’s apparent murder—might seem like the episode’s big twist, the true reveal comes later, as the pilot self-seriously unravels what is so off about our so-called Paradise. It turns out that a massive climate event made the world untenable. “Paradise” is actually a bunker, a simulacrum of society, constructed underneath a mountain in Colorado by a cabal of billionaires. Humanity has been reduced to twenty-five thousand people.

The twist is manna for the moment. The rapacity of Elon Musk, who has seen his plan to hijack the government come to fruition, is a clear inspiration for the drama. The show’s clanking didacticism is deeply satisfying: the plot salad involves climate disaster, nuclear war, and, perhaps most acutely, the insurgency of the billionaire class in politics. Flashbacks show how the old-money Bradford came to become President of the United States, and then President of the bunker, which is to say, nothing more than a puppet nursing a drinking problem in a tree-lined underworld. Julianne Nicholson plays Samantha Redmond, an app developer who prides herself on being the “richest self-made woman in the world.” She has been hardened by the loss of her son, who died, years before the apocalypse, from some mysterious illness. On his deathbed, the boy had asked his mother what heaven would be like. “The thing about heaven, it’s anything you want it to be,” she responded. He imagined a place stacked with coin-operated horse rides. And so Paradise, which would ultimately be constructed by Redmond and her allies, has a symbolic toy horse. Back aboveground, an angry scientist, a kind of prophet character, had grabbed the attention of Redmond, who conspired alongside Bradford and a horde of undifferentiated billionaires to create a bunker in anticipation of catastrophe. In the bunker, Redmond becomes the ringleader; her Secret Service code name is Sinatra.

“Paradise” is about grief and lies. In the Before Times, Sinatra, debilitated by her son’s death, had sought out the assistance of a world-class therapist, Dr. Gabriela Torabi, played by Sarah Shahi. In the bunker, Dr. Torabi confides to Collins about her role in the construction of Paradise, confessing that she personally selected each member of the manufactured society, meaning that she also decided who would get left behind. (“Paradise,” only eight episodes long, off-loads a lot of exposition to its characters.) Other great minds willingly contributed their expertise to the success of the project. The message is bleak. People of means, and people of science, will privilege their own survival in the event of total societal collapse, and they will feel that the decision is justified, even moral. In the world of the show, they are genocidal architects, saving humanity by hacking its destruction.

Much of “Paradise” is hammy as hell. It aspires to simultaneously capture the fleshy intrigues of “Scandal” and the spiritual reckonings of “The Leftovers.” The soundtrack leans on a worn-out motif, downbeat remixes of eighties hair-metal records—“I Think We’re Alone Now,” by Tiffany; “We Built This City,” by Starship—music beloved by the late President Bradford. Marsden and Brown are actors who know how to harness the saccharine, though, burning sugar in order to give the narrative dimension. In a flashback, the President invites Collins into his office. Pouring brown liquor, Bradford orders Collins to take off his shoes. Collins dutifully stoops over and the President stops him, amused. The scene seems a harbinger of the cad President’s sadism, but the relationship mellows out to something of an interracial brotherhood. Bradford trusts no one more than he does Collins, the upstanding man he will never be. Marsden is pleading, pathetic; Brown moored and stifled.

Bradford’s death is a crisis not only because it is a political assassination but because there is no violence in Paradise. Everyone believes that guns were not brought into the underworld. Resentments can be weaponized, though. At the time of the President’s murder, the relationship between Collins and Bradford had soured. The show loves to dole out information in fits, mirroring the characters’ slow understanding of their false new world. We learn that, prior to the apocalypse, the President informed Collins of the impending disaster and promised to grant safe passage to him and his family. On the day the world ended, Collins’s wife, Dr. Teri Rogers-Collins, was in Atlanta, and the President did not get her out in time. The seventh episode is excellent, a disaster movie in miniature, appealing in its visions of thwarted heroism and automated militarization. Taking place almost entirely in flashback, it depicts the fraying of power. A volcano erupts, melts the Antarctic ice sheet, and triggers a tsunami; nations immediately engage in nuclear war, eradicating life. The Secret Service shed their suits and take up machine guns, eventually turning them on the President’s staff. Marsden is so good, the gravity of his moral abdication gradually whitening his beautiful, Ken-doll face. The sentimentalism of “Paradise” is crucial, because it gets the viewer to trust the morality of a show that relies on constant misdirection. “Paradise” is not message television, but it is mawkishly sounding an alarm. It’s disaster entertainment with a sad heart. The survivors in the bunker cope with the world ending as a kind of fait accompli—it was always going to happen, whether by natural disaster or man-made destruction.

As the season develops, further cracks in the edifice of Paradise show. (Spoilers follow.) How complete was this apocalypse? Scientists in the bunker are sent to the surface to search for survivors. They do not return. Back underground, the people are told that the scientists didn’t survive the mission. In Episode 4, we see a different chain of events. Collins, who gets woke, hacks the false sky, and transmits a message in red lights: “They’re lying to you.” He initiates a coup; he and his insurgents locate and raid a secret weapons arsenal. The show’s vision of people power is concentrated in this savior, a grieving Black father who persuades not through speech but through clever police work. A cat-and-mouse game between Collins and Sinatra, the master of the universe, ends with the billionaire cornered. She has her resources, manipulating Collins into putting down his gun. “Maybe I am a monster,” she says to him, smirking. It seems that the billionaire-as-god trope has a little more life left in it after all. ♦