Jesse Eisenberg Is the Man for Our Anxious Moment

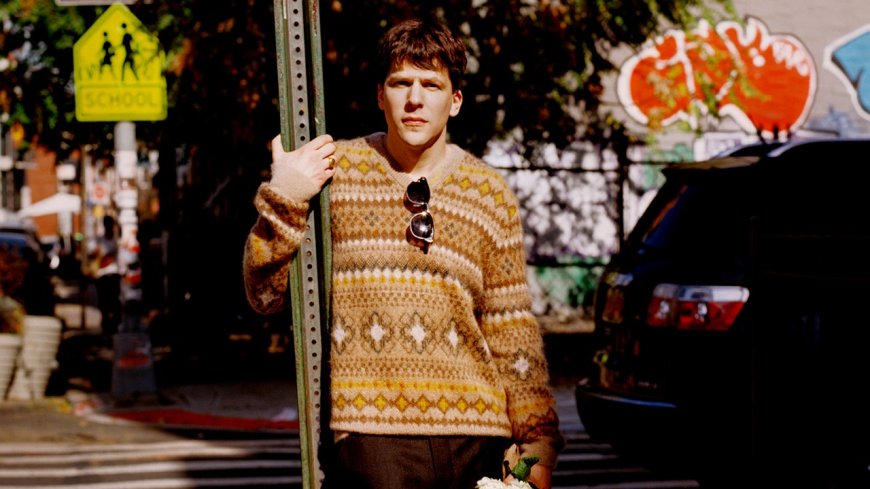

CultureThe master of tightly-wound characters has spent his life envious of people who move through the world with ease. In making his new dark comedy, A Real Pain, he found the upsides to not being that guy.By Olivia OvendenPhotography by Caroline TompkinsDecember 4, 2024Sweater by Louis Vuitton. Pants by Our Legacy. Shoes by Marsell. Sunglasses by Cartier. Necklace, bracelet and ring by Eli Halili.Save this storySaveSave this storySaveJesse Eisenberg is worried about his anxiety levels. Take today, for example. By lunchtime, his mind is already crawling with the brainworms of what might go wrong. As I waited to meet him at the East Village restaurant Little Poland, I spotted Eisenberg outside walking in tight circles on the pavement. He was talking, via Airpods, to his father, who was telling him not to freak out because his new film, A Real Pain, had made the front page of the arts section of the New York Times.“Wait, it is? It is? Oh, it is, how? OK, OK, OK. So that's good, right?’” he said.“Yeah,” his father replied. “It's good.”But really, that is only the beginning. Today is November 1st, and it’s 77 degrees somehow? It’s also the day his film is released in the US? And it’s a story about the suffering of Jewish people, in this political climate? From here it’s only three days until the presidential election and America quite possibly voting for fascism, and so the ghosts swaying from the ceiling might be day-old Halloween decorations, but they also might just be trying to tell us something?“I’ve never been to this restaurant,” he says after coming inside. “I do love Polish food. It’s so weird that I’ve never been here because I wrote a movie called Little Poland which opened in this restaurant, but for some reason I was scared to go in.”Eisenberg, 41, talks in long, melodic paragraphs, his voice halting to edit itself like a cursor running back and forth over each sentence. He arrived today in a storm of polite questions and thank you, thank yous, concerned I might be too cold in here, or that we were late for the lunchtime special.Little Poland has been in New York’s East Village since 1985, its red borscht, boiled perogies and wooden panelling seemingly unchanged since then. It is the sort of timewarp restaurant which might feature in A Real Pain—a place you walk into looking to feel the weight of history and end up feeling a little shortchanged. Eisenberg planted his new film squarely inside that expectation gap, partly inspired by a trip to Poland with his wife to see the last house his ancestors lived in. “I just remember not having the catharsis that I thought I would have in front of this three-story apartment building,” he says. “That dissonance stayed with me.”Eisenberg, who wrote and directed the film, plays David, a neurotic Jewish New Yorker who embarks on a Holocaust memorial tour of Poland with his live-wire cousin Benji, made irresistible by the wayward charm of Kieran Culkin. Eisenberg, who descends from Polish Holocaust survivors, wrote Culkin’s character as a composite of guys he knew growing up, whose ease in moving through the world he found strange and captivating.Unlike David, Benji loves the weird Polish soup they encounter, and makes inroads into the tour group easily, getting strangers to open up about the painful parts of their lives, winning them over even while insulting them. Culkin’s performance is magnificent, but it is seeing him through the watchful eyes of his timid cousin that gives the story its emotional sucker-punch. “Benji shines a light on David, and it’s as though he’s been validated by a God,” says Eisenberg.A Real Pain begins and ends in an airport, dropping Benji into the kind of anonymous spaces that he thrives in, but also showing the loneliness that comes with being the “fun” guy. David’s arc, meanwhile, goes beyond the kind of films that might play his uptight tendencies for laughs. “It’s like meeting the neurotic character but then going to therapy with them and realizing this person is actually struggling with something,” he says. “We’ve been reared to laugh at these comic, sweet protagonists, but most likely this person is also crying themselves to sleep a few nights a week.”Most Saturdays and Sundays for the first 10 years of Eisenberg’s life, his mother would wake at 6am and prepare for her weekend job as a children’s birthday party clown. He remembers hearing her blowing up balloons to fill trash bags with, and tuning her guitar to the piano. “When I told people my mom was a clown they laughed, and yet I saw her taking it as seriously as my dad who was doing work at a hospital,” he says now, folding and unfolding the paper wrapper from his straw. “She would get pulled over sometimes for speeding and she’d be in her costume. It was always shocking to the police and it was awkward, [but] my mom is such a charming woman that she’d always charm the police.”The irony is not lost on him that his mother was a birthday party clown and he was a deeply unh

Jesse Eisenberg is worried about his anxiety levels. Take today, for example. By lunchtime, his mind is already crawling with the brainworms of what might go wrong. As I waited to meet him at the East Village restaurant Little Poland, I spotted Eisenberg outside walking in tight circles on the pavement. He was talking, via Airpods, to his father, who was telling him not to freak out because his new film, A Real Pain, had made the front page of the arts section of the New York Times.

“Wait, it is? It is? Oh, it is, how? OK, OK, OK. So that's good, right?’” he said.

“Yeah,” his father replied. “It's good.”

But really, that is only the beginning. Today is November 1st, and it’s 77 degrees somehow? It’s also the day his film is released in the US? And it’s a story about the suffering of Jewish people, in this political climate? From here it’s only three days until the presidential election and America quite possibly voting for fascism, and so the ghosts swaying from the ceiling might be day-old Halloween decorations, but they also might just be trying to tell us something?

“I’ve never been to this restaurant,” he says after coming inside. “I do love Polish food. It’s so weird that I’ve never been here because I wrote a movie called Little Poland which opened in this restaurant, but for some reason I was scared to go in.”

Eisenberg, 41, talks in long, melodic paragraphs, his voice halting to edit itself like a cursor running back and forth over each sentence. He arrived today in a storm of polite questions and thank you, thank yous, concerned I might be too cold in here, or that we were late for the lunchtime special.

Little Poland has been in New York’s East Village since 1985, its red borscht, boiled perogies and wooden panelling seemingly unchanged since then. It is the sort of timewarp restaurant which might feature in A Real Pain—a place you walk into looking to feel the weight of history and end up feeling a little shortchanged. Eisenberg planted his new film squarely inside that expectation gap, partly inspired by a trip to Poland with his wife to see the last house his ancestors lived in. “I just remember not having the catharsis that I thought I would have in front of this three-story apartment building,” he says. “That dissonance stayed with me.”

Eisenberg, who wrote and directed the film, plays David, a neurotic Jewish New Yorker who embarks on a Holocaust memorial tour of Poland with his live-wire cousin Benji, made irresistible by the wayward charm of Kieran Culkin. Eisenberg, who descends from Polish Holocaust survivors, wrote Culkin’s character as a composite of guys he knew growing up, whose ease in moving through the world he found strange and captivating.

Unlike David, Benji loves the weird Polish soup they encounter, and makes inroads into the tour group easily, getting strangers to open up about the painful parts of their lives, winning them over even while insulting them. Culkin’s performance is magnificent, but it is seeing him through the watchful eyes of his timid cousin that gives the story its emotional sucker-punch. “Benji shines a light on David, and it’s as though he’s been validated by a God,” says Eisenberg.

A Real Pain begins and ends in an airport, dropping Benji into the kind of anonymous spaces that he thrives in, but also showing the loneliness that comes with being the “fun” guy. David’s arc, meanwhile, goes beyond the kind of films that might play his uptight tendencies for laughs. “It’s like meeting the neurotic character but then going to therapy with them and realizing this person is actually struggling with something,” he says. “We’ve been reared to laugh at these comic, sweet protagonists, but most likely this person is also crying themselves to sleep a few nights a week.”

Most Saturdays and Sundays for the first 10 years of Eisenberg’s life, his mother would wake at 6am and prepare for her weekend job as a children’s birthday party clown. He remembers hearing her blowing up balloons to fill trash bags with, and tuning her guitar to the piano. “When I told people my mom was a clown they laughed, and yet I saw her taking it as seriously as my dad who was doing work at a hospital,” he says now, folding and unfolding the paper wrapper from his straw. “She would get pulled over sometimes for speeding and she’d be in her costume. It was always shocking to the police and it was awkward, [but] my mom is such a charming woman that she’d always charm the police.”

The irony is not lost on him that his mother was a birthday party clown and he was a deeply unhappy child, missing a year of school because he was institutionalized for mental health issues. Growing up he felt out of sync with everyone else cruising through each day as though every minute didn’t feel life or death. “It was just mystifying to me why we weren’t all crying all day long because it just seemed like the world is so sad and scary,” he says. “Maybe that’s what part of this movie is: I would watch people like Kieran’s character and just wonder, How are they existing? Don’t they know school is tomorrow as well? Don’t they know the summer is transient and we have to come back here? Don’t they know they’re not going to see their parents all day tomorrow?”

This whirling internal tempest—which settles as we talk and he looks me in the eye for longer and longer stretches—is part of what has made Eisenberg so compelling as an actor, whether as a teenager embittered by his parents’ divorce in Noah Baumbach’s 2005 film The Squid and the Whale, or as an asshole Trojan-horsed into a fretful father in the recent hit series Fleishman Is In Trouble. His talent for telegraphing a hive of activity behind the scenes was apparent early in his career, even if it wasn’t always what was required. “I remember the first movie I was in, Rodger Dodger, the director kept saying to me, “More Woody Harrelson, less Woody Allen!”” he recalls. “The character did have a lightness, but I was imbuing him with this deep anxiety.”

This tendency to wear his heart on his sleeve was why he found playing Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network such a fun challenge, given his interior life had to remain so closed off. “He’s someone who at once knows exactly who he is and doesn’t have any perception of who he is,” he says. “[His] interactions with other people are these kind of stilted puzzles he has to try and figure out, because he can’t really perceive [their emotions].”

Growing up, Eisenberg realised that being funny was a way to armor yourself. “Nobody laughs at the funny guy,” a childhood friend once told him, and he thought, Huh, that’s right. Eisenberg has used comedy not only in the characters he plays, but also in writing humor pieces for the New Yorker, and a short story collection, Bream Gives Me Hiccups, which is now being turned into a TV series. There is a claustrophobic quality to his writing that can feel like being trapped in a lift with a stranger’s raw emotions rubbing up against you, a sensation which you feel in A Real Pain, and the previous film he wrote and directed, 2022’s When You’re Finished Saving The World.

“I love comedy so much, but I’m a sad person in general, so it comes out like this,” he says. Eisenberg assumed that everyone else was using jokes as a way to mask inner pain. At least, until he met Ricky Gervais. Eisenberg was depressed at the time, and recalls asking him: “Are you depressed? No? Well then, how are you funny? Is it that you’re self-conscious? Is it that you hate yourself?”

“And he goes, ‘No, it’s none of those things. I really love making jokes, and I love being around people who are making jokes,’” Eisenberg tells me now, at the speed you’re probably imagining, but faster. “It's the first time I ever heard that. And I was thinking, ‘Oh, maybe that's some kind of cultural difference’. Then I also remember thinking, ‘Oh, the reason he's saying this to me is because I'm bringing him really way down right now.’”

Eisenberg pauses to think in front of his vegetarian stuffed cabbage, which arrived so large he had to quickly relinquish the menu he had held onto, and which tastes so good he is worried it’s surely going to give him food poisoning, because anything good will manifest something terrible. “His stuff I’m suspicious of though, because it’s really tinged with a lot of sadness,” he says. “So I don’t exactly believe him.”

If Eisenberg hadn’t been so prone to introspection then he thinks maybe he would never have had a career in the arts. He’d be a banker, living in the suburbs, which of course is totally fine, but it would be a less examined life. I tell him that, on balance, I would take my neurosis rather than living in ignorant bliss. “Or is that just a way you justify your own misery so that you don’t kill yourself?” he says. “I don’t mean to be glib about your impending suicide, but is that just what sad people tell themselves, that it’s giving them depth?”

There have been certain moments in Eisenberg’s life which he remembers as deeply happy. One was during the pandemic, when he volunteered at Middle Way House, the domestic abuse shelter his mother-in-law founded in Indiana. He spent his days painting walls, plumbing and learning to fix the garbage disposal from the building manager, Floyd. Working with a clear purpose and in service to others, he felt the calm of doing something that takes you outside of your own head.

Afterwards he wrote his first feature film, When You’re Finished Saving The World, about a mother, Evelyn (Julianne Moore), who runs a domestic abuse shelter but cannot be charitable toward her shallow son Ziggy (Finn Wolfhard). Seeing the noble work of a domestic abuse shelter up close might inspire another writer to pen a moving drama about social justice, but not Eisenberg. “She’s arguably deserving of some kind of hagiography,” he says. “But isn’t the more interesting story to see how this person can’t navigate this other world?”

While talking he breaks off to thank our waiter in Polish. Eisenberg asks where he is from, which is Ukraine, and then asks after his family. For a second I don’t know what horrors we are about to hear, but all he says is “Good—pretty good” with a vacant smile. It is an exchange which has an Eisenberg reality-check quality to it; this is how strange and often flat life really is.

“Jesse understands implicitly that what we intend is not necessarily how we behave,” Julianne Moore tells me. “You would think that would be a given in lots of screenplays, but it’s not. You watch these people desperately trying to understand each other and missing.” Moore—who will star alongside Paul Giamatti in Eisenberg’s next film, a musical set in the high-stakes world of community theater—says Eisenberg is a “triple threat, as someone who understands acting, writing and directing.”

A Real Pain was the first time he was using all of those muscles at once, and he had to learn so many things, all while resisting the urge to have some huge personal catharsis in these places of historical significance. He also had to get accustomed to watching himself for the first time. Until now he’s always hated to see himself back. The director David Fincher did so many takes for The Social Network—half of them really socially removed and aloof, and half more naturalistic—and Eisenberg has no idea which version of Zuck he ended up playing, because he still hasn’t watched the movie. But editing A Real Pain meant he simply had to get over it.

“I have developed a thick skin because of acting. I know the worst of what people write about me and my body and my face,” he says. “I don’t feel that as much with writing because it’s so less reflective of who I am. The thing you don’t like about your nose is the same thing New York Magazine hates about your nose. The thing you read on a messageboard is the same thing you hate about your hair. That’s so deeply humiliating.”

After lunch we had planned to walk around the Strand bookstore, but Eisenberg passed it on his way here and reports that it is in fact incredibly crowded. Honestly, he worries that he was wired for a life much more stressful than the one he’s currently living. Take today, for example—because sure, the reviews are good, but tonight. Tonight he has to do a Q&A for the film at a movie theater, and what if it’s empty? “Somebody's gonna tell me how much they hated the movie and then the rest of the audience is gonna realize that they also hated the movie too, and if it wasn't for this one intuitive person in the room, they wouldn't have realized that,” he says, occasionally coming up for air. “And then the press is gonna be there, and they're gonna realize we were also hoodwinked!”

These thoughts might sound extreme, but these days it feels as though our age of anxiety is finally rising to meet Eisenberg’s panic levels. Look online, and in the street and on the news—shouldn’t we all be a little more worried? And, really, he does worry. He’s just finished filming Now You See Me 3, and his hyper-confident street magician character is the most joyful part to play, because he’s not allowed to let any self-doubt in, and banishing nerves from his body gives him a kind of afterglow after he walks off set. “Every other movie I've ever been in is just: ‘That was terrible. Can we please just do another [take]? And I’m so sorry, because it’s also going to be bad.’”

A Real Pain is about learning to live with not being easygoing, or charming. Eisenberg wrote Benji as a way to work through “family members or relationships I've had that make me feel inadequate.” At one point David tells his cousin, “You see how people love you? You see what happens when you walk into a room? I would give anything to know what that feels like, man.”

This dynamic played out between the two actors on set. Right before production was due to begin, Culkin tried to quit. When they did make it on set, Eisenberg amusedly recalls him being "explicitly resistant” to being told what to do. Culkin says that he didn’t want to plan, sure that Eisenberg had written something so clear he understood what was required. “Before the last shot of the film, at the airport, he came up to me and [said], ‘Do you want to talk about what happens here in the scene?’” Culkin tells me. “And I said ‘No, no, please go away’, apparently. And he just, like, ran away.”

Eisenberg grew up envious of the Benji effect, but he now understands that there is a loneliness to being that guy; everyone has their demons. There are also superpowers that come with being the emotionally open, gentle guy, too. One day, on the set of When You’re Finished Saving The World, the young lead, Wolfhard, was starting to panic. He loved the script so much and really wanted to get it right, and yet he found himself dissolving. “I pulled Jesse aside and told him I was pretty stressed out and was apologizing,” Wolfhard tells me. “He told me this story about having a similar issue with anxiety on set. It made me calm down a lot, because it made it seem like it was fine to be anxious and not feel like you’re weird for having those kinds of feelings.”

“It’s helped me in life,” Wolfhard adds. “Sometimes if I mess up a line I’ll remember Jesse saying it’s not a big deal. It’s definitely made being an anxious person more comfortable, which is nice.”

Eisenberg hadn’t expected to find a kindred spirit in Wolfhard, “a 6ft 3in gorgeous rock star, in addition to being an actor”, assuming he would be the most confident guy in the world. The depth and self-consciousness he displayed was not only great for the film, but it also gave Eisenberg something he knew how to help with.

Eisenberg’s interest in other people also struck Claire Danes, who played his wife in Fleishman Is In Trouble. “He’s incredibly interested in everyone he meets, and he’s not kidding. It’s initially a little unsettling, but people are very touched he cares,” says Danes. “He wants to get into it really quickly, and really thoroughly.” This was echoed by Culkin, who told me if he did direct he’d want to do it the way Eisenberg does, through listening. “He knew exactly what he wanted, but really wanted to hear people’s thoughts,” he says.

After Fleishman aired, Eisenberg would be approached by people in the street, telling him desperately sad things about their marriages ending, and the most vulnerable parts of their lives. “I’m an emotional actor, I’m not a jock. I can’t imagine the same person opening up to, like, Jason Statham or something,” he says—then adding quickly, as though worried Statham might be cracking his knuckles reading this, “Maybe he wants that? I don’t know. I think I just appear like somebody who would be sympathetic to a story.”

Of course, the price of curiosity, of wanting to go deep with people—of genuinely caring—is that you come to realize how scary and fragile the world really is. Perhaps you don’t get the curiosity without the anxiety; perhaps the anxiety is part of the deal.

I experience this curiosity with Eisenberg firsthand, as I find myself offloading about my personal life, only an hour after meeting him. He keeps asking questions—about what I want from a partner, or where my surname is from—and then really listening, so much so that I realize I’ve run over time, and he’s been too polite to say anything, but now he’s very sorry and really does have to leave. “I was wondering how tall you were,” he says, as we stand up to say goodbye. “I figured about that tall.”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Caroline Tompkins

Styled by Haley Gilbreath

Grooming by Melissa DeZarate