How Assad’s Regime Crumbled

Q. & A.Iran’s weakness, a faltering economy, and new political fissures led to the stunning end of a dynasty.By Isaac ChotinerDecember 9, 2024Photograph by Omar Haj Kadour / GettyOver the weekend, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad fled to Russia as opposition forces took over the capital of Damascus, ending an uprising that had begun in 2011 and killed hundreds of thousands of people, and displaced millions. Assad’s regime had appeared to have gained the upper hand after receiving significant military support from Iran and Russia. But with his allies tied down with conflicts against Israel and Ukraine, respectively, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (H.T.S.), a rebel group once affiliated with Al Qaeda under its former name, Al Nusra Front, marched with stunning speed across Syria’s major cities.To understand what this turn of events means for Syria’s neighbors and how the country might achieve a semblance of normalcy, I recently spoke by phone with Emile Hokayem, the director of regional security and a senior fellow for Middle East security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, who has written extensively on Syria for almost two decades. During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we also discussed the internal dynamics that led the Assad regime to decline, why Assad’s onetime regional enemies remain concerned, and what the rebels who overthrew the government really want.Over the past forty-eight hours, we’ve seen people celebrating Assad’s fall, but what are you most concerned about right now and why?I think everyone’s concern has to do with the factionalism that has pervaded not just the opposition, but Syria. The regime itself was as fractured as the opposition has been in the past. Syria has a Kurdish population, and ISIS is still rearing its ugly head in the eastern desert. So some part of the country was unified for a long time around Assad because he seemed like the lowest common denominator. But that became part of the reason he fell. The opposition became relatively more united because it had one enemy to rally against. Now we are essentially going back to a competition for power, for territory, for legitimacy. And that is going to be the difficult task here—to rise above that.But I don’t think we should be cynical. Just because it was hard in the past and that it didn’t succeed elsewhere doesn’t mean that the Syrians will fail. There is a strong argument for optimism here based on the fact that this was in a way a purely Syrian victory, or a Syrian solution to a Syrian problem. This was not an international or a regionally backed effort that led to the demise of Assad. That it was a bottom-up process may actually serve to reduce some of these divisions.Specifically, the fact that we have avoided the so-called Qaddafi moment—that essentially Bashar al-Assad was not captured and killed, which happened with Qaddafi in a pretty gruesome way—could serve to diffuse tensions. Had we had a Qaddafi moment, I think the way it would’ve played into the Syrian confessional universe would have been worrisome, and that would’ve been the overwhelming image.Because it would have been the majority religious group, Sunnis, murdering someone—even if he might deserve it—someone from a minority sect, in this case the Alawites?Exactly. In a way, yes, it’s sad that he escaped, and there’s certainly going to be very, very legitimate calls for justice. But avoiding this violent culmination of that process—although there is still violence and I’m not whitewashing what’s happening—and not having that one moment, the one picture that crystallizes all the fears, does help.You said that this was a Syrian solution to a Syrian problem. Does that imply that you think the role of Turkey in supporting this group, H.T.S., is overstated?Certainly. Turkey is the big geopolitical winner, but I think we need to provide some context there. First, Turkey is not a direct sponsor of H.T.S. It is actually the sponsor to another coalition called the Syrian National Army, which brought remnants of other groups together. And if anything, H.T.S., although it comes from a radical jihadist past, has actually been quite disciplined in this space and in recent years has avoided some of the extreme behavior that Turkish-supported groups like the S.N.A. have not. I would argue the S.N.A. is a more problematic force in this regard.I don’t believe, and a number of other analysts don’t believe, that Turkey masterminded the march to Damascus from Day One. I think the Turks had in mind limited achievements in and around Aleppo. The rebels wanted to push further, but the Turks were on board for a limited operation. It’s just that the speed at which things happened, the momentum that the rebels gathered, essentially overtook initial calculations. I think that this march and this frenetic advance is largely due to momentum that the rebels themselves were a bit surprised about.But more fundamentally, and I think this is the key fa

Over the weekend, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad fled to Russia as opposition forces took over the capital of Damascus, ending an uprising that had begun in 2011 and killed hundreds of thousands of people, and displaced millions. Assad’s regime had appeared to have gained the upper hand after receiving significant military support from Iran and Russia. But with his allies tied down with conflicts against Israel and Ukraine, respectively, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (H.T.S.), a rebel group once affiliated with Al Qaeda under its former name, Al Nusra Front, marched with stunning speed across Syria’s major cities.

To understand what this turn of events means for Syria’s neighbors and how the country might achieve a semblance of normalcy, I recently spoke by phone with Emile Hokayem, the director of regional security and a senior fellow for Middle East security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, who has written extensively on Syria for almost two decades. During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we also discussed the internal dynamics that led the Assad regime to decline, why Assad’s onetime regional enemies remain concerned, and what the rebels who overthrew the government really want.

Over the past forty-eight hours, we’ve seen people celebrating Assad’s fall, but what are you most concerned about right now and why?

I think everyone’s concern has to do with the factionalism that has pervaded not just the opposition, but Syria. The regime itself was as fractured as the opposition has been in the past. Syria has a Kurdish population, and ISIS is still rearing its ugly head in the eastern desert. So some part of the country was unified for a long time around Assad because he seemed like the lowest common denominator. But that became part of the reason he fell. The opposition became relatively more united because it had one enemy to rally against. Now we are essentially going back to a competition for power, for territory, for legitimacy. And that is going to be the difficult task here—to rise above that.

But I don’t think we should be cynical. Just because it was hard in the past and that it didn’t succeed elsewhere doesn’t mean that the Syrians will fail. There is a strong argument for optimism here based on the fact that this was in a way a purely Syrian victory, or a Syrian solution to a Syrian problem. This was not an international or a regionally backed effort that led to the demise of Assad. That it was a bottom-up process may actually serve to reduce some of these divisions.

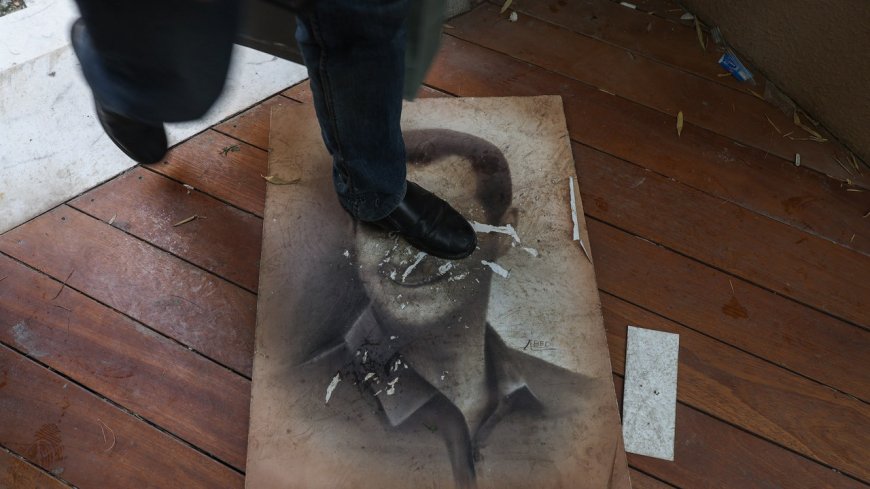

Specifically, the fact that we have avoided the so-called Qaddafi moment—that essentially Bashar al-Assad was not captured and killed, which happened with Qaddafi in a pretty gruesome way—could serve to diffuse tensions. Had we had a Qaddafi moment, I think the way it would’ve played into the Syrian confessional universe would have been worrisome, and that would’ve been the overwhelming image.

Because it would have been the majority religious group, Sunnis, murdering someone—even if he might deserve it—someone from a minority sect, in this case the Alawites?

Exactly. In a way, yes, it’s sad that he escaped, and there’s certainly going to be very, very legitimate calls for justice. But avoiding this violent culmination of that process—although there is still violence and I’m not whitewashing what’s happening—and not having that one moment, the one picture that crystallizes all the fears, does help.

You said that this was a Syrian solution to a Syrian problem. Does that imply that you think the role of Turkey in supporting this group, H.T.S., is overstated?

Certainly. Turkey is the big geopolitical winner, but I think we need to provide some context there. First, Turkey is not a direct sponsor of H.T.S. It is actually the sponsor to another coalition called the Syrian National Army, which brought remnants of other groups together. And if anything, H.T.S., although it comes from a radical jihadist past, has actually been quite disciplined in this space and in recent years has avoided some of the extreme behavior that Turkish-supported groups like the S.N.A. have not. I would argue the S.N.A. is a more problematic force in this regard.

I don’t believe, and a number of other analysts don’t believe, that Turkey masterminded the march to Damascus from Day One. I think the Turks had in mind limited achievements in and around Aleppo. The rebels wanted to push further, but the Turks were on board for a limited operation. It’s just that the speed at which things happened, the momentum that the rebels gathered, essentially overtook initial calculations. I think that this march and this frenetic advance is largely due to momentum that the rebels themselves were a bit surprised about.

But more fundamentally, and I think this is the key factor, it exposed the hollowness and the rot of the Assad regime. The loyalist constituencies of Assad decided that it wasn’t worth fighting. Why? Because Assad defeated his enemies, and they stopped posing an existential threat to him. But there were no victory dividends the day after, and that really hurt his constituency. He won, but there were no positive returns economically.

Who was his constituency?

It was a very diverse one that included Alawite individuals and clans that have benefitted from the regime and served in key security functions. But it extended to a senior Sunni officer corps, and to a large section of the Sunni urban, élite middle class, upper class. It included members of minorities: Armenians, Christians, others. It was a disparate coalition that supported him first and foremost because he was the rampart against Islamists, broadly defined. And they shed a lot of blood for him. They suffered profoundly, and they justified Assad’s murderous campaign in the previous decades.

But these constituencies, and their economic and social fortunes, declined since victory was achieved. Assad did not have the mind-set, did not have the plan, did not have the resources to make things better, including for his constituency. If anything, his regime grew more predatory, more rapacious, more violent in the past few years. It never regained cohesion. It never regained a sense of purpose.

There’s an argument being made that the most important foreign backers of Assad, such as Hezbollah, Iran, and Russia, withdrew their support or weren’t able to provide the same levels of support, and that caused the regime to collapse. I assume you think that’s part of the reason, but it also seems like you’re saying something distinct.

Look, I don’t deny the significant contribution that the weakening of Iran and the overstretch of Russia had in all this. But the speed at which the regime forces collapsed and the total absence of those popular militias which had rallied in the past and the fact that Assad did not have a narrative mattered. He did not appear once on television in the past ten days. All this points to the utter hollowness of his regime and the fact that it had essentially lost the support of all these constituencies that were key to survival during the prior iteration of that war, between 2011 and 2017. I don’t think one can understand what happened if one ignores that significant dynamic. So yes, there’s certainly a geopolitical context for all this, but there is Syrian agency. There are local conditions that have allowed this to happen the way it did happen. And keep in mind the economic collapse, and the fact that they lost access to the Lebanese economy.

Is that because of international sanctions on Syria, or because of various problems in Lebanon?

In part, it’s sanctions, but more important it’s the collapse of the Lebanese financial sector and economy since 2019. And that was essentially Syria’s economic lung. They were trading through Lebanon, they were money laundering through Lebanon, they were putting their savings in Lebanon.

What signals are you reading for hope and concern? I assume the most obvious one is just how non-Sunni groups are going to be treated.

The first point I would make is that this war hasn’t ended just yet. Just because the large cities have been liberated from Assad’s control should not make us forget that on Sunday there was fighting in northern Syria between the S.N.A. and the Kurds. Yesterday, the U.S. bombed more than seventy-five ISIS positions in the eastern desert and the Israelis expanded their control of the Golan Heights and bombed a number of facilities. And importantly, a number of Assad’s militias have now retreated to the coastal areas, and there is a fear that they can still defend themselves. A lot of them are hardened men who have fought in the past and are very worried about their future. So the potential for more violence does exist. And it’s not the day after; we’re not there yet. There is a lot in flux.

The second point is that some of the rebel factions are quite disciplined. And it’s clear that H.T.S., led by Abu Mohammad al-Julani, has developed the language, has talked about policy positions, and wants to come across as the mature party. I don’t want to whitewash their record. It may change, and one should not be naïve about these groups. But the key thing is to see whether stability and order can be brought to the large cities quickly. If you have large-scale chaos in Damascus or Homs or Aleppo, one is going to struggle to put some kind of political process on track.

There is the question of whether there’s anything from the past ten years of political negotiations that can be put on the table. There were a lot of initiatives, including one by the U.N. to define a new constitution for Syria, to include Syria’s massive diversity. Are there ready-made plans or ideas that can be deployed? And with a group like H.T.S., which is listed as a terrorist organization by the U.S. and others—Julani himself is considered a terrorist by the U.S. and others—how are they brought into the tent? Orchestrating that choreography where you need to bring in the remnants of the regime, too, will be complex.

It does require regional support, but at a time when Europe is exhausted, Russia is on the back foot, the U.S. is going through a transition and Trump has already said the U.S. should have nothing to do with Syria, the multilateral system is battered. So who orchestrates that? Is it going to be Turkey leading? And, if Turkey leads, will the others accept? Is Turkey going to think about this in terms of just the stabilization of Syria or as part of its power play with Iran and Russia?

How are the Sunni states thinking about Assad’s fall? Because they were broadly supportive of getting rid of Assad for a while, and then they were concerned about ISIS. And then it seemed like Assad had won and they reached out to him.

In a way, there’s a sweet irony. Ten years ago, many of the Arab states wanted Assad gone and the Syrians were divided. Now most of the Syrians want Assad gone, but most of the Arab states wanted him to stay. Not because they loved him, but because prior attempts had failed, the cost was significant, and because the region is on fire. So a number of countries basically were telling themselves, We don’t want yet another crisis on our hands. Everyone recognizes Syria is a central geopolitical theatre. Because of its geography, Syria is pivotal. Not because it has great strength or a booming economy or plenty of resources. It’s purely a question of geography.

Syria is a theatre in which at any one day, the U.S., Russian, Turkish, Iranian, and Israeli militaries are operating. Can you think of another place in the world that has this variety of large important militaries engaging in operations, plus jihadis?

The reality is that the region is stunned by what happened. I just spent a couple of days with Middle Eastern officials, very senior ones, and I can tell you they’re struggling. They had written Syria off. Most of them wanted to normalize with Assad because they made very flawed assumptions about Syria. And they’re not the only ones. The Italians had decided to normalize with Assad and had sent an ambassador for the first time back to Damascus last month.

But they got Syrian society wrong. And, when you see the reaction in the main cities, it’s mostly positive about that change. So now all these states have to figure out: Who are these new players in Syria? And importantly, these new players will feel that they don’t owe foreigners much. You know, in the previous round there was international support, but there was also international abandonment after the chemical-weapons attack. That’s what’s so important for Syrians now—they did it themselves, so they don’t owe the region much.

You said Syria is so important because all these outside actors have decided to make it central to their interests. But is that because there’s something unique about the place, or just because the geopolitics of the past twenty years happened to lead to this outcome?

I think it’s important because of its geography, because of all the borders it has with so many significant states; because it’s where Turkish-Arab competition plays out, where Arab and Iranian competition plays out, where Israel is keen on asserting its security interests and so on. And increasingly, it’s because of Syria’s role as a hub for migration and for drug-trafficking and for terrorism. It’s not necessarily intrinsically about Syria and Syrians; it’s about Syria as this hub for a lot of negative dynamics. Just to be clear, I’m offering you a geopolitical reading. It’s also important for Syrians.

One thing that has not come up much in this conversation is that the Gulf states and Israel are happy that this is a defeat for Iran. Do you think that element has been overstated?

These actors had all preferred a weak, deterrable Assad over this traumatic transformation. The U.S. really was not planning on that change. If anything, its policy was moving toward limited reëngagements. The Gulf states wanted to turn the page on political transformations in the Arab world. And Israel was fine with Assad as long as it could fly over Syria, bomb anything it wanted, and not be challenged. Are they pleased that Iran is weakened? Yes.

Syria is central to Iran’s position in the region, to the resupply of Hezbollah. So this is a monumental setback for Iran, in part because it had already spent so much money and shed so much blood saving Assad the first time only to see this investment essentially disappear. And I suspect, in Iran, there’s a lot of introspection about the cost of supporting all these weak actors.

So Iran is definitely weakened, but Iran has been resilient in the past. What happens depends on how the Iranians absorb that shock, whether there is a recognition in Iran that actually the axis of resistance is not that popular, that it actually sits on weak societies and weak states—which means that it’s not real power at the end of the day, and that these are costly endeavors.

But also these actors have posed a very high risk to Iran. If Hamas starts something, and that ends up in a potential Israel-U.S.-Iran war with exchanges of missiles, that’s not what the Iranians wanted. So you support those militia partners, thinking that they amplify your influence, and in fact, they entangle you in crises that you struggle to keep up with. And that’s where the Iranians are. ♦