Family Discord and Holiday Music in “Cult of Love” and “No President”

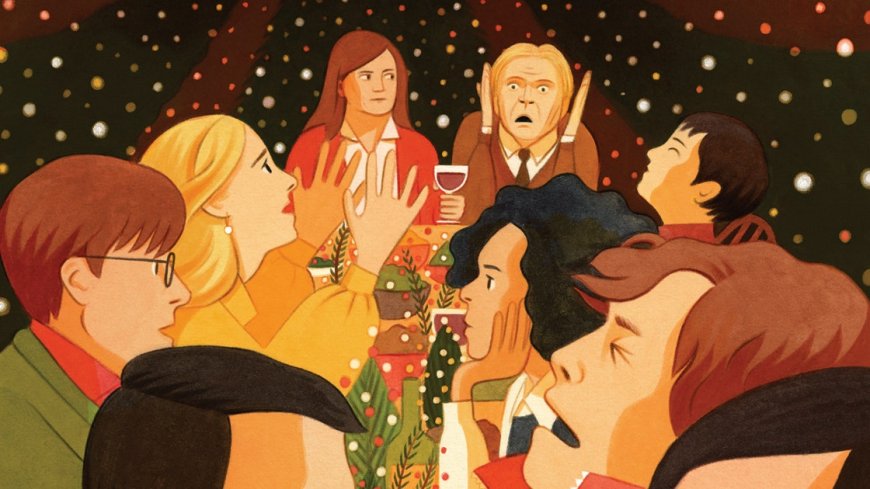

The TheatreTwo scathing new productions satisfy our hunger for dysfunction-driven entertainment.By Helen ShawDecember 13, 2024In Leslye Headland’s drama, a family’s attempts at harmony fall flat.Illustration by Eleni KalorkotiThe first image of Leslye Headland’s family drama,“Cult of Love,” on Broadway at the Hayes, looks like a Christmas card. Behind a gauzy scrim, most members of the ten-person cast pose in festive symmetry, carefully arranged around a living room glowing with a thousand holiday lights. We consider this tableau for a moment, before the scrim rises and the action begins. The prefatory pause gives the audience a chance to applaud a starry ensemble. It also signals that what we’re about to see is glossy—and a little false.We’re in the seemingly blissful home of an intensely Christian family, the Dahls, and the elders—Ginny (Mare Winningham, Tony-nominated in 2022 for “Girl from the North Country”) and her mentally deteriorating husband, Bill (David Rasche, who played a consigliere on “Succession”)—have summoned their adult children home for the holiday. The family members regularly break into impressively harmonized, Osmond-family-level carol arrangements that they’ve clearly been singing together forever. Some of the siblings’ spouses might roll their eyes, but they often join in, shaking a maraca here, playing a washboard there.At first, everyone’s feeling a bit Grinchy because Ginny won’t serve Christmas Eve dinner until the sweetheart of the family, the recovering heroin addict Johnny (Christopher Sears), arrives with his friend and fellow N.A. member Loren (Barbie Ferreira). These two have learned to be frank about their issues, unlike the rest of the family, who remain in undeclared crisis. The onetime theologian Mark (Zachary Quinto) and his wife, Rachel (Molly Bernard), are hiding a separation. The pregnant Diana (Shailene Woodley), a zealot, and her Episcopal-priest husband, James (Christopher Lowell), can’t stop making homophobic comments as Evie (Rebecca Henderson) and her new wife, Pippa (Roberta Colindrez), grit their teeth. (Henderson and Headland, the playwright, are married in real life.) Dad, meanwhile, is losing his memory, though Mom won’t admit it. The play’s most chilling line is delivered wryly by Pippa. “Like it or not, you are the parents now,” she tells the quarrelling siblings, before splitting for her Airbnb.“Cult of Love,” which Headland has said is based on her own family, is this season’s domestic slugfest, a Broadway staple with a history stretching back at least to Clifford Odets’s lyrical “Awake and Sing!” (1935). But “Cult,” first performed in 2018, moves faster and throws wilder punches than other works in its category. Headland has been making films and TV shows for a decade now—she co-created the Netflix series “Russian Doll”—and in the play’s hundred-minute running time you sense conflicting methods at work. She and her director, Trip Cullman, expertly ratchet up tension with overlapping dialogue, using it to demonstrate the rhythms of addiction and relapse. (Our own hunger for dysfunction-driven entertainment is, sadly, its own kind of dependence.)Headland does sometimes overload the table with narrative. When she takes a breath, though, she creates moments of genuine connection, as when Bill, exuding amnesiac fondness, pleads for peace among his children. Woodley nails Diana’s mean-waif combustibility, and both Colindrez and Ferreira, playing outsiders unimpressed with their welcome to the Dahl house, do lovely work. Elsewhere, however, Headland’s TV training undermines her. She seems to have needed a few more episodes for all the character arcs and pontificating speeches to land.“Cult of Love” has a subtitle, “Pride,” which refers both to the hubris of faith and to one of the seven deadly sins; Headland has written a series of plays based on each one. In 2010, she made a splash with the gluttonous girls-gone-bad comedy “Bachelorette.” Two years later, she wrote the greed-themed office farce “Assistance,” informed by her own stint working for Harvey Weinstein. In Headland’s “dirty dioramas,” as she calls those works, there’s usually an alpha—a leader whose behavior infects everyone below them in the pack. In “Cult of Love,” the alpha is Ginny, the family’s Denier-in-Chief, played by Winningham with frightening precision. Usefully, Winningham has a beautiful but nasal folk-song twang, which—whether she’s singing or speaking—cuts through the other, merely pretty voices.“Cult of Love,” unlike the other “sin” plays, was written when Headland was in her thirties, after she married Henderson, whose character, Evie, can be seen as Headland’s stand-in. Evie’s addiction—one that she battles as much as Johnny does narcotics and Mark does God—is to the toxic family itself. Should she give them up? Performing an intense psychodrama about your wife’s family, night after night, must be gruelling. Henderson approaches the task with crisp gravity, ceding the right of

The first image of Leslye Headland’s family drama,“Cult of Love,” on Broadway at the Hayes, looks like a Christmas card. Behind a gauzy scrim, most members of the ten-person cast pose in festive symmetry, carefully arranged around a living room glowing with a thousand holiday lights. We consider this tableau for a moment, before the scrim rises and the action begins. The prefatory pause gives the audience a chance to applaud a starry ensemble. It also signals that what we’re about to see is glossy—and a little false.

We’re in the seemingly blissful home of an intensely Christian family, the Dahls, and the elders—Ginny (Mare Winningham, Tony-nominated in 2022 for “Girl from the North Country”) and her mentally deteriorating husband, Bill (David Rasche, who played a consigliere on “Succession”)—have summoned their adult children home for the holiday. The family members regularly break into impressively harmonized, Osmond-family-level carol arrangements that they’ve clearly been singing together forever. Some of the siblings’ spouses might roll their eyes, but they often join in, shaking a maraca here, playing a washboard there.

At first, everyone’s feeling a bit Grinchy because Ginny won’t serve Christmas Eve dinner until the sweetheart of the family, the recovering heroin addict Johnny (Christopher Sears), arrives with his friend and fellow N.A. member Loren (Barbie Ferreira). These two have learned to be frank about their issues, unlike the rest of the family, who remain in undeclared crisis. The onetime theologian Mark (Zachary Quinto) and his wife, Rachel (Molly Bernard), are hiding a separation. The pregnant Diana (Shailene Woodley), a zealot, and her Episcopal-priest husband, James (Christopher Lowell), can’t stop making homophobic comments as Evie (Rebecca Henderson) and her new wife, Pippa (Roberta Colindrez), grit their teeth. (Henderson and Headland, the playwright, are married in real life.) Dad, meanwhile, is losing his memory, though Mom won’t admit it. The play’s most chilling line is delivered wryly by Pippa. “Like it or not, you are the parents now,” she tells the quarrelling siblings, before splitting for her Airbnb.

“Cult of Love,” which Headland has said is based on her own family, is this season’s domestic slugfest, a Broadway staple with a history stretching back at least to Clifford Odets’s lyrical “Awake and Sing!” (1935). But “Cult,” first performed in 2018, moves faster and throws wilder punches than other works in its category. Headland has been making films and TV shows for a decade now—she co-created the Netflix series “Russian Doll”—and in the play’s hundred-minute running time you sense conflicting methods at work. She and her director, Trip Cullman, expertly ratchet up tension with overlapping dialogue, using it to demonstrate the rhythms of addiction and relapse. (Our own hunger for dysfunction-driven entertainment is, sadly, its own kind of dependence.)

Headland does sometimes overload the table with narrative. When she takes a breath, though, she creates moments of genuine connection, as when Bill, exuding amnesiac fondness, pleads for peace among his children. Woodley nails Diana’s mean-waif combustibility, and both Colindrez and Ferreira, playing outsiders unimpressed with their welcome to the Dahl house, do lovely work. Elsewhere, however, Headland’s TV training undermines her. She seems to have needed a few more episodes for all the character arcs and pontificating speeches to land.

“Cult of Love” has a subtitle, “Pride,” which refers both to the hubris of faith and to one of the seven deadly sins; Headland has written a series of plays based on each one. In 2010, she made a splash with the gluttonous girls-gone-bad comedy “Bachelorette.” Two years later, she wrote the greed-themed office farce “Assistance,” informed by her own stint working for Harvey Weinstein. In Headland’s “dirty dioramas,” as she calls those works, there’s usually an alpha—a leader whose behavior infects everyone below them in the pack. In “Cult of Love,” the alpha is Ginny, the family’s Denier-in-Chief, played by Winningham with frightening precision. Usefully, Winningham has a beautiful but nasal folk-song twang, which—whether she’s singing or speaking—cuts through the other, merely pretty voices.

“Cult of Love,” unlike the other “sin” plays, was written when Headland was in her thirties, after she married Henderson, whose character, Evie, can be seen as Headland’s stand-in. Evie’s addiction—one that she battles as much as Johnny does narcotics and Mark does God—is to the toxic family itself. Should she give them up? Performing an intense psychodrama about your wife’s family, night after night, must be gruelling. Henderson approaches the task with crisp gravity, ceding the right of tragedy, as almost everyone does, to Rasche’s Bill. His memory issues, papered over by his unlistening wife, fade from the play’s attention—they aren’t climax material—but you’ll remember them, or at least I did, in the days afterward.

The same weekend that I saw “Cult of Love,” I also saw “No President,” the avant-garde group Nature Theatre of Oklahoma’s latest show. The production, at the Skirball, is a two-and-a-half-hour dance-theatre marathon, featuring a full corps de ballet, performed without a break. The company, which has won multiple Obie Awards and international acclaim, has endured its own family psychodrama, related to the multiyear project “Life and Times.” (There was a rupture between the company’s leaders, Pavol Liska and Kelly Copper, and its members.)

Like the Dahl household, the nightmarish “No President”—subtitled a “A Story Ballet of Enlightenment in Two Immoral Acts”—relies on holiday music to distract us from interpersonal grotesquerie. An extended recording of Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker” plays while a narrator, Robert M. Johanson, magniloquently intones the show’s plot, which the dancers perform and mime. There are no mice, no soldiers; instead, Johanson relates a grisly, bizarro fable about an actor turned security guard (Ilan Bachrach) whose Père Ubu-like ascent to tyrannical power involves frequent sexual abuse (often of him, by a dancing group of “personal demons”) and a cannibalistic approach to a war that he’s waging against another security firm.

Liska and Copper’s balletic staging begins as a delight and then deliberately overstays its welcome. In story-ballet mode, the corps brings the main characters’ props onstage—such as scarves that represent the blood of the security guard’s many victims—and then exits with glad little jetés. Ha ha, off they go! But the nine thousandth little jeté might make you want to scream. You will find it provocative, or punishing, in the same measure that you enjoy other surreal horror projects. I was reminded of the French artist Christian Boltanski’s video-loop work “L’Homme Qui Tousse,” from 1969, in which a man vomits fake blood onto his chest, seemingly forever, and of Casper Kelly’s short film “Too Many Cooks,” from 2014, which obsessively repeats a faux-sitcom theme song. (What is funny becomes boring becomes funny becomes frightening.)

As is common practice these days, this major downtown performance was staged for only three days. The show lampoons the prim, tutu-clad aesthetic of high European culture, but it also depends on that culture’s remains: there is not enough support in the U.S. for such audacious, resource-intensive work, so the show was jointly commissioned by the Ruhrtriennale, Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, and Bard College. I was grateful to have the Nature Theatre of Oklahoma back, battering my consciousness, but I felt a little disheartened at the echoes of “Cult of Love” ’s acidic score-settling. Johanson’s narrator refers frequently to the narcissism of actors and their hunger for approval. Liska and Copper’s text also, uncomfortably, makes constant, slighting reference to Bachrach’s body. (The security guard did not merely take a bath; he “stuffed” himself into the bathtub, Johanson says.) “You want the spotlight?” I imagine the Nature Theatre’s alphas asking. “This is how it burns.” But that’s what we expect from our holiday entertainment these days. All our theatre-makers are angry kids, and you are the parents now. ♦