‘Carry-On’ Is Cool, But the Two 2000s Thrillers It’s Inspired By are Better

CultureIf you liked Netflix’s new Christmas thriller, you should love these Colin Farrell and Cillian Murphy gems from the early aughts.By Frazier TharpeDecember 17, 2024Chris Panicker; Everett CollectionSave this storySaveSave this storySaveThis is an edition of the weekly newsletter Tap In, GQ senior associate editor Frazier Tharpe’s final word on the most heated online discourse about music, movies, and TV. Sign up here to get it free.You don’t go into a Jaume Collet-Sera thriller expecting a reinvented or even lightly innovated wheel. He’s a B-movie maestro, with a skill for making a brand new film feel as if it’s something you’ve half-seen on TNT a dozen times already. (Although I will genuinely, earnestly ride for House of Wax and The Shallows—arguments for another column perhaps.) Most of his films feature an increasingly grizzled Liam Neeson in the midst of some insane scenario—murder conspiracy on an in-transit flight, “reverse amnesia,” etc.—taken to and then beyond its logical extension for peak, controlled ridiculousness. After a couple snoozefests in RockLand that I didn’t even bother to see, JCS is back in his bag with a new muse in Taron Egerton and a new What If: suppose a TSA agent was threatened into letting something really bad through security?Taron is no Liam, but Carry-On is pretty solid nonetheless—the three-star-out-of-five film that it was born to be, to adopt the Letterboxd ranking scale here. But it wasn’t long before both the core concept and the setting had me thinking about the other, better films that it reminded me of. Save for a sparse handful of tense in-person faceoffs, the film pits Egerton’s would-be heroic LAX TSA officer, Ethan, against Jason Bateman’s diabolical bad guy—unnamed throughout the film and credited only as The Traveler—via an earpiece. With the help of an off-site evil tech henchman with access to the airport cameras and Google, The Traveler is in Ethan’s head literally and figuratively: he can see Ethan’s every move, and he has enough information to psychoanalyze him and hopefully manipulate him into doing his bidding. And Ethan, being in a professional rut made even more pronounced by the news that he’s going to be a father, is feeling especially insecure. There are stretches where the Traveler’s needling of Ethan—about his station in life, his failure to launch, his shortcomings as a partner—makes this hostage situation feel more like a harsh therapy session.Shades of Collateral, which, in between the assassinations, is really just a bromance dramedy. (Out of all of the indelibly classic scenes in that film, the last one in the cab still hits the hardest: “What the fuck are you still doing driving a cab?”) But comparing a Netflix thriller to one of the best movies ever made is unfair. What Carry-On really took me back to was two early-aughts films that both serve as showcases of how truly insane that era was when it came to letting auteurs cook with ludicrous premises. A terrorist working within the confines of an airport/airplane to execute a political agenda for shadowy clients? That’s all Red Eye, the 2005 Wes Craven movie that jams Rachel McAdams in the economy seat from hell next to Cillian Murphy. And a homicidal maniac lodged into his victim’s ear for the film’s duration? That has the DNA of a film from three years earlier in the extremely 2002 Phone Booth, one of the nuttier star vehicles of this century.It’s not even that they’re vastly better films—all three are ridiculous in their own ways, in both a laugh-at and laugh-with capacity—but respectfully, it’s hard for the Carry-On crew to formidably box with Colin Farrell, Kiefer Sutherland and Joel Schumacher or McAdams, Murphy, and Wes Craven. Both films have loglines that would be Rod Serling wet dreams and, unlike Carry-On’s flabby two-hour runtime, don’t overstay their welcome, getting in and out at around 80 minutes.Carry-On’s twin conceits—the disembodied tormentor and the airport claustrophobia—were extended to more fun extremes by Craven and Schumacher, respectively. By placing the action on an actual airplane, Craven ramps that claustrophobia up by about 65% even if it’s at the expense of any sense of believability that any of this could be unfolding with no one around Murphy and McAdams being the wiser. That doesn’t matter when Cillian is leaning into arch-villainy even more than he would in the Dark Knight trilogy, versus Rachel McAdams in one of a handful of roles where she proves she deserves more than Hollywood sometimes offers her.Schumacher, of course, is dialed in even higher, staying in and outside the titular phone booth, cheating ever so slightly with crowd shots as Farrell’s predicament draws a mob of New York City onlookers. In doing so, it places all bets on Farrell and Sutherland exercising contrasting muscles, in service of the same flex: movie-star gravitas. In a true commitment to the bit that Carry-On cops out on shockingly early, Sutherland and Farrell legit never ph

This is an edition of the weekly newsletter Tap In, GQ senior associate editor Frazier Tharpe’s final word on the most heated online discourse about music, movies, and TV. Sign up here to get it free.

You don’t go into a Jaume Collet-Sera thriller expecting a reinvented or even lightly innovated wheel. He’s a B-movie maestro, with a skill for making a brand new film feel as if it’s something you’ve half-seen on TNT a dozen times already. (Although I will genuinely, earnestly ride for House of Wax and The Shallows—arguments for another column perhaps.) Most of his films feature an increasingly grizzled Liam Neeson in the midst of some insane scenario—murder conspiracy on an in-transit flight, “reverse amnesia,” etc.—taken to and then beyond its logical extension for peak, controlled ridiculousness. After a couple snoozefests in RockLand that I didn’t even bother to see, JCS is back in his bag with a new muse in Taron Egerton and a new What If: suppose a TSA agent was threatened into letting something really bad through security?

Taron is no Liam, but Carry-On is pretty solid nonetheless—the three-star-out-of-five film that it was born to be, to adopt the Letterboxd ranking scale here. But it wasn’t long before both the core concept and the setting had me thinking about the other, better films that it reminded me of. Save for a sparse handful of tense in-person faceoffs, the film pits Egerton’s would-be heroic LAX TSA officer, Ethan, against Jason Bateman’s diabolical bad guy—unnamed throughout the film and credited only as The Traveler—via an earpiece. With the help of an off-site evil tech henchman with access to the airport cameras and Google, The Traveler is in Ethan’s head literally and figuratively: he can see Ethan’s every move, and he has enough information to psychoanalyze him and hopefully manipulate him into doing his bidding. And Ethan, being in a professional rut made even more pronounced by the news that he’s going to be a father, is feeling especially insecure. There are stretches where the Traveler’s needling of Ethan—about his station in life, his failure to launch, his shortcomings as a partner—makes this hostage situation feel more like a harsh therapy session.

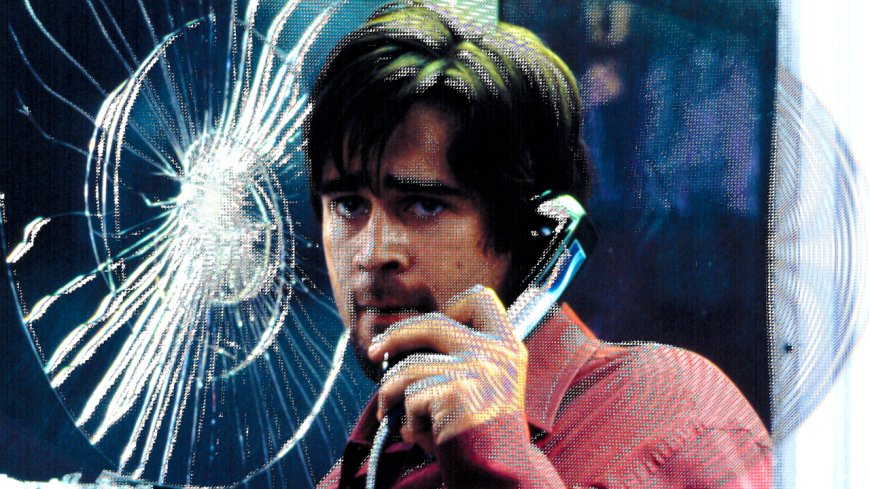

Shades of Collateral, which, in between the assassinations, is really just a bromance dramedy. (Out of all of the indelibly classic scenes in that film, the last one in the cab still hits the hardest: “What the fuck are you still doing driving a cab?”) But comparing a Netflix thriller to one of the best movies ever made is unfair. What Carry-On really took me back to was two early-aughts films that both serve as showcases of how truly insane that era was when it came to letting auteurs cook with ludicrous premises. A terrorist working within the confines of an airport/airplane to execute a political agenda for shadowy clients? That’s all Red Eye, the 2005 Wes Craven movie that jams Rachel McAdams in the economy seat from hell next to Cillian Murphy. And a homicidal maniac lodged into his victim’s ear for the film’s duration? That has the DNA of a film from three years earlier in the extremely 2002 Phone Booth, one of the nuttier star vehicles of this century.

It’s not even that they’re vastly better films—all three are ridiculous in their own ways, in both a laugh-at and laugh-with capacity—but respectfully, it’s hard for the Carry-On crew to formidably box with Colin Farrell, Kiefer Sutherland and Joel Schumacher or McAdams, Murphy, and Wes Craven. Both films have loglines that would be Rod Serling wet dreams and, unlike Carry-On’s flabby two-hour runtime, don’t overstay their welcome, getting in and out at around 80 minutes.

Carry-On’s twin conceits—the disembodied tormentor and the airport claustrophobia—were extended to more fun extremes by Craven and Schumacher, respectively. By placing the action on an actual airplane, Craven ramps that claustrophobia up by about 65% even if it’s at the expense of any sense of believability that any of this could be unfolding with no one around Murphy and McAdams being the wiser. That doesn’t matter when Cillian is leaning into arch-villainy even more than he would in the Dark Knight trilogy, versus Rachel McAdams in one of a handful of roles where she proves she deserves more than Hollywood sometimes offers her.

Schumacher, of course, is dialed in even higher, staying in and outside the titular phone booth, cheating ever so slightly with crowd shots as Farrell’s predicament draws a mob of New York City onlookers. In doing so, it places all bets on Farrell and Sutherland exercising contrasting muscles, in service of the same flex: movie-star gravitas. In a true commitment to the bit that Carry-On cops out on shockingly early, Sutherland and Farrell legit never physically interact. In fact, the only time we ever see Sutherland’s face in frame, the picture is distorted and hazy, he never even looks dead-on at the camera. It’s a performance anchored entirely on Sutherland’s distinct, gravelly voice—the manic hoarse yelling that became the stuff of TV legend shortly after this on 24, but also softly-purred threats and wry, sardonic one-liners. He’s tasked with building a complete character entirely off-screen; he may as well be in a 1940s radio play. Colin, on the other hand, in full one-man play mode, bargaining, pleading and eventually begging all while staying committed to a ridiculous Irish New York accent.

Again, right when both of these films threaten to crumble under the weight of their house-of-cards storytelling, they pull the rug out and wrap it up. But even though neither would rank high in any of the filmographies of anyone involved, the difference between them and Carry-On is the hand of actual auteur filmmakers rather than a journeyman who knows how to make a good crowd—or in this case, home-for-the-holidays living room—pleaser. Nothing against Carry-On; it’s a fine return to form. But if you enjoyed it, add these to the queue for an even better time.