A Complete Unknown Director James Mangold Has Words For All You Music-Biopic Haters

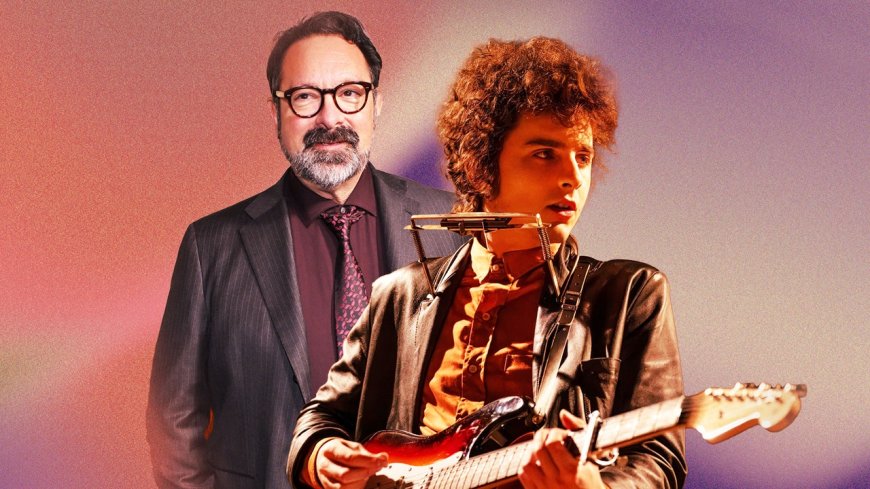

CultureThe Oscar-nominated helmer of Timothée Chalamet's Bob Dylan film talks artistic license, Dylan and Johnny Cash's bond, and how his Bob is like Boba Fett.By Jack KingJanuary 24, 2025Getty, SearchlightSave this storySaveSave this storySaveThe following article contains spoilers for A Complete Unknown.2025 may go down as the year the universe of music biopics expanded faster than the MCU. The Oscar-nominated A Complete Unknown, which recounts the early-'60s career of Bob Dylan (Timothée Chalamet) as he evolves from folk music messiah to electric Judas, is just the latest—soon to come are four separate movies about The Beatles, a Bruce Springsteen film starring The Bear's Jeremy Allen White, and even a sure-not-to-inspire-any-controversy flick about Michael Jackson.It's all on the heels of the awards success of Bohemian Rhapsody, for one. But if any one director can be said to have perfected the music-biopic blueprint, it's James Mangold, with 2005's Walk the Line, about country legend Johnny Cash (Joaquin Phoenix) and his tempestuous relationship with June Carter (Reese Witherspoon). In the two-decade period since Walk the Line's release, Mangold (who just scored a Best Director nomination, his second, for A Complete Unknown) has established himself as a go-to studio filmmaker with a unique knack for what makes a blockbuster sing, his movies typically standing out in the era of uninventive IP churn. Just look at 2017's Logan, rightly considered one of the greatest superhero movies of all time, and his riotous 2019 Le Mans biopic Ford v Ferrari (known by Mangold's favored title, Le Mans '66, in Europe), both of which epitomize his interest in deeply human, emotionally driven stories, even within the construct of the traditional tentpole.But now he returns to the music-biopic space at its moment of peak saturation, tackling a subject who's challenged the greatest of movie-makers, from Todd Haynes (2007's I'm Not There) to Martin Scorsese (2005's No Direction Home, 2019's Rolling Thunder Revue). Mangold takes a comparably direct approach to retelling the early life and myth of Bob Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman, beginning with his arrival in New York City, through to his rapid ascent and eventual stardom. Mangold has described it as a fairytale, and his movie has the magical feel of one—such is the incredible, folkloric nature of a then 19-year-old Dylan's rise from anonymity to one of the most powerful cultural voices on the world stage.GQ spoke to Mangold about taking on the music biopic once again with A Complete Unknown, his view on the purpose of biographical movies, and why Chalamet was the right guy for Bob.They’re very different movies, but a lot of people consider Walk the Line to be one of the core texts for the modern music biopic. So were you apprehensive at all about returning to that genre space?No. I’m always conscious, when returning to a genre, of trying to address how to make the genre fit the moment, and how to address moving the genre forward—in a sense, not making a carbon copy of what’s been before, whether it’s my own work or others’. I mean, it’s kind of too deep, but I think the pejorative way people refer to musical biopics is laughable to me, in the sense that, why are we not so nervous about the clichés and tropes and forms of the superhero movie, or the monster movie? Why is Nosferatu somehow exempt from that, or… You can pick any one of these movies: the standard Oscar drama, the issue-driven da-da-da. They all have their tropes.I mean, I don’t know whether it’s the fact that [music biopic parody and largely Walk The Line-influenced] Walk Hard was made—but Young Frankenstein was made. So do we never make another monster movie? Blazing Saddles was made. Do we never make another Western? There’s an odd prism through [which] people view what I feel is such a natural cinematic form. Music and film are brothers, and they braid together so beautifully. Recorded pictures and music are both twins of the 20th century that grew up at the same time, and it’s only natural that there would be a form that unites them.I’m genuinely curious about the evolution of the music biopic, because there’s been so much iteration.I’d just say: is it even a genre? Is it a genre like a western is a genre? Many movies are based on true-life events, does the fact that the true-life person makes music make it in-and-of itself a genre? When Boba Fett first straps on his blaster, is that any different than Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan or Johnny Cash first strapping on his Gibson? To me, as a maker of movies, they’re not so different.When it comes to biographical movies more broadly, what should they set out to do?I think what you’re doing is telling a fable, or a kind of fairytale, but it’s also based upon a reality. I don’t think they’re supposed to be Wikipedia entries. I think what biographical movies offer us is the chance to experience the world, and the tone, and the vibe, and the feeling of that place a

The following article contains spoilers for A Complete Unknown.

2025 may go down as the year the universe of music biopics expanded faster than the MCU. The Oscar-nominated A Complete Unknown, which recounts the early-'60s career of Bob Dylan (Timothée Chalamet) as he evolves from folk music messiah to electric Judas, is just the latest—soon to come are four separate movies about The Beatles, a Bruce Springsteen film starring The Bear's Jeremy Allen White, and even a sure-not-to-inspire-any-controversy flick about Michael Jackson.

It's all on the heels of the awards success of Bohemian Rhapsody, for one. But if any one director can be said to have perfected the music-biopic blueprint, it's James Mangold, with 2005's Walk the Line, about country legend Johnny Cash (Joaquin Phoenix) and his tempestuous relationship with June Carter (Reese Witherspoon). In the two-decade period since Walk the Line's release, Mangold (who just scored a Best Director nomination, his second, for A Complete Unknown) has established himself as a go-to studio filmmaker with a unique knack for what makes a blockbuster sing, his movies typically standing out in the era of uninventive IP churn. Just look at 2017's Logan, rightly considered one of the greatest superhero movies of all time, and his riotous 2019 Le Mans biopic Ford v Ferrari (known by Mangold's favored title, Le Mans '66, in Europe), both of which epitomize his interest in deeply human, emotionally driven stories, even within the construct of the traditional tentpole.

But now he returns to the music-biopic space at its moment of peak saturation, tackling a subject who's challenged the greatest of movie-makers, from Todd Haynes (2007's I'm Not There) to Martin Scorsese (2005's No Direction Home, 2019's Rolling Thunder Revue). Mangold takes a comparably direct approach to retelling the early life and myth of Bob Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman, beginning with his arrival in New York City, through to his rapid ascent and eventual stardom. Mangold has described it as a fairytale, and his movie has the magical feel of one—such is the incredible, folkloric nature of a then 19-year-old Dylan's rise from anonymity to one of the most powerful cultural voices on the world stage.

GQ spoke to Mangold about taking on the music biopic once again with A Complete Unknown, his view on the purpose of biographical movies, and why Chalamet was the right guy for Bob.

They’re very different movies, but a lot of people consider Walk the Line to be one of the core texts for the modern music biopic. So were you apprehensive at all about returning to that genre space?

No. I’m always conscious, when returning to a genre, of trying to address how to make the genre fit the moment, and how to address moving the genre forward—in a sense, not making a carbon copy of what’s been before, whether it’s my own work or others’. I mean, it’s kind of too deep, but I think the pejorative way people refer to musical biopics is laughable to me, in the sense that, why are we not so nervous about the clichés and tropes and forms of the superhero movie, or the monster movie? Why is Nosferatu somehow exempt from that, or… You can pick any one of these movies: the standard Oscar drama, the issue-driven da-da-da. They all have their tropes.

I mean, I don’t know whether it’s the fact that [music biopic parody and largely Walk The Line-influenced] Walk Hard was made—but Young Frankenstein was made. So do we never make another monster movie? Blazing Saddles was made. Do we never make another Western? There’s an odd prism through [which] people view what I feel is such a natural cinematic form. Music and film are brothers, and they braid together so beautifully. Recorded pictures and music are both twins of the 20th century that grew up at the same time, and it’s only natural that there would be a form that unites them.

I’m genuinely curious about the evolution of the music biopic, because there’s been so much iteration.

I’d just say: is it even a genre? Is it a genre like a western is a genre? Many movies are based on true-life events, does the fact that the true-life person makes music make it in-and-of itself a genre? When Boba Fett first straps on his blaster, is that any different than Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan or Johnny Cash first strapping on his Gibson? To me, as a maker of movies, they’re not so different.

When it comes to biographical movies more broadly, what should they set out to do?

I think what you’re doing is telling a fable, or a kind of fairytale, but it’s also based upon a reality. I don’t think they’re supposed to be Wikipedia entries. I think what biographical movies offer us is the chance to experience the world, and the tone, and the vibe, and the feeling of that place and time, as opposed to their first order of business being a timeline of facts and dates. What I think the movies offer you, that is actually incredibly useful, is a kind of immersion into this emergent moment in history, in which you can suddenly realize very modest things—like how young these people were, and how when history is being made, the participants are very often not aware that history is being made.

I should imagine from a creative perspective that there is some level of tension between historical accuracy, and then creating a piece of art, and then also making something that is entertaining.

The tension you’re describing doesn’t exist in quite the same way that you’re articulating it, in the sense that our first order of business is always to tell it how it happened. And the word “entertaining” is a kind of cheap word—“dramatic” is the word I’d use. If there were three meetings in an apartment where something happened, and I can dramatize the actual course of events with two scenes, or one scene, should I fade out and fade in on another day, just because it happened over three days and not one? It seems, dramatically, like malfeasance… I don’t even understand when that comes up.

Moving on to A Complete Unknown, I’d be curious to know whether there was a particular performance or quality of Timothée’s that made you feel he was the right guy to play Dylan.

He’s one of the really great young actors of his time. His work reveals a real intelligence. Bob Dylan is, if anything, marked by a kind of rabid intelligence. It was always important to me that whoever plays Bob Dylan finds a way to both live uncomfortably in the present of his career, but also has a secondary life going on all the time in his mind… There’s so much articulation about Dylan as being arrogant, or difficult, or an enigma, or all of the above, and I felt that all those things are dramatically inert ideas.

There's a bracing sequence set around a Dylan performance at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis. How much of that was artistic invention, and why did you want to include it?

I can't offer you off the cuff my citations, but I can tell you that the song ["Masters of War"] came about from the Cuban Missile Crisis and was written during it… I can't tell you right now who told me that he went out—I think it might've been Bob, but I think it was also in a book, that probably had come from him, that he was trapped in the city during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and he was alone, and he went out and wrote that song, as well as other political songs. That all came out of him in the midst of that period.

So again, when you're making a film like this, you're kind of operating with this stew of everyone's memories of dates, and how things fell. But what seemed undeniable to me, to all the principles involved, was that Sylvie's [Elle Fanning, playing a character based on Suze Rotolo] absence, the Cuban Missile Crisis, et cetera, created this kind of flowering moment for Bob to write the first political anthems that he was starting to write.

Why did you want to highlight Dylan's friendship with Johnny Cash?

Well, it was profound. Cash provided a kind of devil on the other shoulder. Bob had plenty of pressure to hue to the kind of folk line, the tribal rules of the folk music world—but Bob never bought that dogma. So Johnny Cash, first of all, had a real pen pal relationship with him. These letters in the movie are the actual words of the letters that were exchanged between them. I felt like Johnny Cash represented a kind of anarchy or respect for messiness that was interesting, and that he was both part of the folk world and embraced by it, but also colored outside of the lines.

And by the way, there was some hypocrisy there, because Johnny Cash was allowed for years to show up with his band and play at Newport, and never had any issue whatsoever. Because in a sense Bob was their center tentpole, the pressure for Bob not to succumb to becoming a rock star was much greater.

And a brief word on the Newport show right at the end of the movie—it's kind of implied that Cash's blessing primes Dylan to go electric, right? Tell me about the inspiration for that moment.

Well, it comes from the letters. First of all, rumor has it that it was Johnny who gave him the guitar he went out and used for “Baby Blue” at the end. [Editor's note: Cash was not actually at Newport ‘65, so the ending of A Complete Unknown is mostly artistic license, but Cash did allegedly hand the guitar over to Dylan at Newport ’64.] But also, in John's letters, one of the phrases he uses was “track mud on someone's carpet.” He says that twice in the movie, and those are Johnny Cash's words to Bob. Meaning that his attitude—and what he encouraged young Bob to do—was to push the boundaries, and in a sense, that's exactly what Bob did.

I'm not trying to say that Bob did it because of Johnny, but that Johnny was offering Bob [the] permission structure and encouragement that you should follow your gut, not the conscripts of this tribunal.

This interview originally appeared in British GQ.