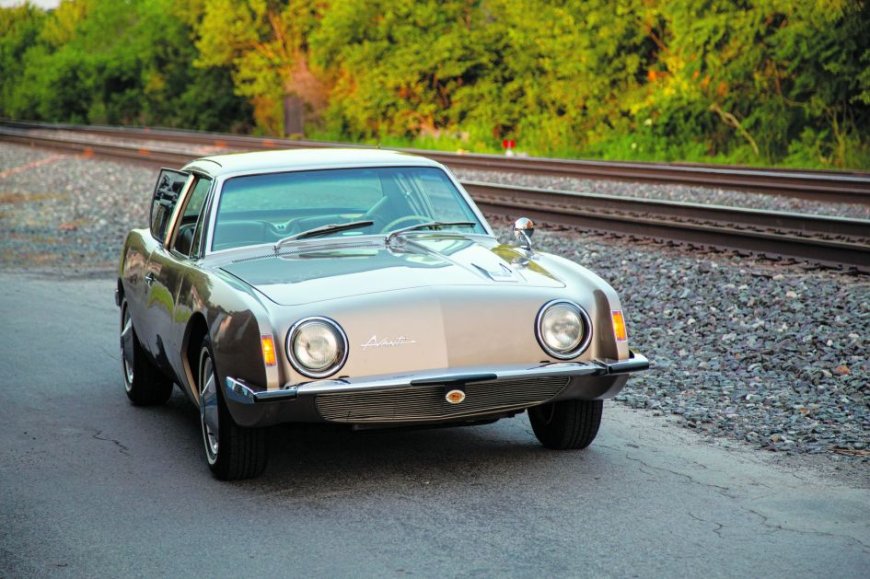

This all-original 1963 Studebaker Avanti has enjoyed a charmed life

Volumes of literary art have been written about Studebaker. It’s okay to assume that much of the cumulative composition has focused on the brand’s humble beginnings before segueing to the latter years of cheapness, both in terms of vehicle affordability and purported build quality during the latter decades of production. Authors then turn their attention… The post This all-original 1963 Studebaker Avanti has enjoyed a charmed life appeared first on The Online Automotive Marketplace.

Volumes of literary art have been written about Studebaker. It’s okay to assume that much of the cumulative composition has focused on the brand’s humble beginnings before segueing to the latter years of cheapness, both in terms of vehicle affordability and purported build quality during the latter decades of production. Authors then turn their attention to the Packard merger gone wrong before culminating with a handful of logical “what if” hypotheses that could have kept Studebaker solvent for decades.

Nearly lost in the oft-recounted blend of reality and folklore is that Studebaker was a highly respected company when it came to advanced styling, creative engineering, and luxurious trappings. One glance at the list of vehicles recognized as Full Classics by the Classic Car Club of America is proof positive—the 1928 President (powered by an eight-cylinder engine), 1929-1933 President (except the Model 82), and 1934 President, are all included. Even during the immediate postwar years, Studebaker was celebrated for being the first established automaker to offer completely new, modern styling—in 1947. Studebaker has similarly been lauded for its cash-strapped creative engineering in the late Fifties and early Sixties.

Yet it’s virtually impossible to connect any of those acclaimed postwar achievements without mention of the oft-told catalyst for the last to have happened at all. In brief, the fantastic redesign unveiled for 1947 eventually played second fiddle to the rest of the well-funded industry. Brief salvation arrived with 1953’s redesign effort, though by then maneuvering modest sales into positive cash flow was already an uphill battle. The introduction of the compact Lark IV in 1959 was a well-timed blessing. Consumers were finally hungry for a spacious and attractive economical car, and Studebaker reaped the reward of its immediate success. But the good fortune was short lived. Ford and Chevrolet both entered the compact race within a year, and the compact car spigot was wide open by 1961.

In yet another corporate attempt to right the ship, the Gran Turismo Hawk arrived on the scene for 1962, which provided fresh, racy styling bolstered with ample power. It was a small step in the right direction and, in hindsight, the new model foreshadowed things to come. That’s because Studebaker President Sherwood Egbert tasked designer Raymond Loewy to fashion a luxury sports coupe as an attention-getting halo car. The concept had worked for Chevrolet in 1953 and Ford in 1955 with the Corvette and Thunderbird, respectively; logic said it should do the same for Studebaker.

The four-man enterprise, Loewy included, plied their trade in a Palm Springs, California home, and designed what looked to be a completely new car—going from nothing to a clay mockup—in just 40 days. It seems an incredible feat were it not for the fact that due to Studebaker’s dire fiscal situation, the team had to work with what was already developed. This meant the car would use a modified X-braced Lark convertible frame, with torque boxes added for rigidity; its wheelbase measured 109 inches. Conventional Lark suspension parts were used: control arms, coil springs, shocks and anti-roll bar up front, and semi-elliptic leaf springs and hydraulic shocks at the opposite end. A rear anti-roll bar and radius rods were added at the rear as well.

What was lavish by 1963 standards was the use of 11.5-inch front disc brakes with two-piston calipers. Although other manufactures had experimented with disc brakes, Studebaker’s use of a caliper-based system was a first on a regular-production domestic vehicle. They were complemented by 11 x 2-inch rear drums. Power assist was also a standard feature.

For power, the new car received South Bend’s existing “Jet-Thrust” 289-cu.in. engine, introduced in 1956, though it received some tweaks. One was a lower intake manifold, done so to provide proper hood clearance, which received a new four-barrel carburetor. Along with some other upgrades, the engine—designated R-1—boasted a rating of 240 hp and an estimated 280 lb-ft of torque, although some resources list a lofty torque rating of 305.

The “Jet-Thrust” name was also attached to the optional R-2 engine. This was a 289 similar to the R1, except that it featured cylinder heads with larger combustion chambers for a lower 9.0:1 compression ratio. It also had a belt-driven, fixed-ratio Paxton SN-60 centrifugal supercharger. Providing 4.5 pounds of boost, the R-2’s output achieved the magical one horsepower per cubic inch, while torque jumped to an estimated 303 lb-ft. (Editor’s note: a second option, though one never really publicly announced, was the R-3 that surfaced for 1964. It was an engine massaged by the Granatelli brothers that boasted 304-cu.in., a Paxton SN supercharger that provided 6 pounds of boost to a 650-CFM Carter four-barrel, and 335 hp and 320 lb-ft of torque in factory trim.)

A three-speed manual transmission was standard, though it would later prove to be unpopular among buyers who preferred either the four-speed manual or “Power-Shift” three-speed automatic options. The latter two made use of center console shifter locations in the car’s aircraft-inspired cabin, which included four bucket seats, a bank of overhead rocker switches that controlled cabin lighting and fan, and a padded structural roll bar incorporated into the B-pillars.

Arguably, the most intriguing feature was the car’s sleek, long hood/short deck body. Fiberglass was selected over steel, primarily due to tooling costs. Initially produced by the Molded Fiberglass Body Company in Ashtabula, Ohio, body production was later moved in-house. Trim was becoming increasingly scant in the domestic industry, and the new Studebaker was no exception. In fact, it didn’t have a conventional grille, but rather a flat, canted panel that sported “Avanti” script, Italian for “forward.”

First shown in 1962, the Avanti received a warm welcome; however, the public honeymoon was short lived. Despite news of Andy Granatelli shattering 29 U.S. speed records in a special R-3 equipped Avanti at the Bonneville Salt Flats, in addition to setting a flying mile record of 170.78 mph—giving Studebaker claim to the World’s Fastest Production Car—production delays stalled delivery dates to customers. Just 3,834 were built in 1963, and another 809 in 1964, before Studebaker ceased production at its South Bend, Indiana, facility in December 1963.

Depicted on these pages is a first-year Avanti now under the care of Paul and Ann Rose, of Pennsylvania. Thiers is an R-1 equipped edition that was ordered in December, built in late-March and delivered new in April 1963 from Packard Lancaster Co, Inc., in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. It is one of less than 500 equipped with a four-speed manual transmission. The first owner kept the car for nearly eight years, using it sparingly. He took it to the nearby Manheim Auto Auction in 1970 to sell, but the Avanti did not reach its reserve price.

Elmer Swipenhizer from Scranton, Pennsylvania, the owner of a repair service for Studebakers, noticed the car at that auction. He bid on it unsuccessfully, though approached the seller, made an offer, and gave him a business card. Two years passed and the original owner contacted Elmer and accepted the original offer. Elmer kept the Avanti for 10 years. He, too, used the car very little; albeit for one trip to the National Studebaker Show in Tennessee—he drove there and back—where it received both first place and long-distance awards.

Elmer sold the Avanti to John Kehoe of Tara Alta, West Virginia, who owned it for eight years; still another owner who barely used the car. The Roses became its fourth owner on July 18, 2014. “I was looking for an Avanti. I had joined the Studebaker Club and found it for sale on the club website where it was listed as a low-mileage car. The owner was surprised to hear from me, as he had taken the car off the market two years prior to my calling,” Paul says.

When he bought the Studebaker, painted Avanti Gold, the original tires and wheels were still with it, but not installed. “The car was in driving condition, but in need of catch-up maintenance and small repairs. We returned the Avanti to a road-worthy state and reinstalled the original tires and wheels for car shows,” Paul says. To this day, the Avanti has never been restored and only repaired as needed. Its odometer reads just 12,000 miles from new.

Among the treasures that came with the stylish Studebaker are its original build sheet, window sticker, Avanti dealer sales book, and factory inspection report with the word “rolls” noted—each manual transmission equipped Avanti was dyno-tested at South Bend prior to shipment. Paul notes that the original “Swipe” service tags are still intact on the driver’s side door jamb, and he jokingly adds, “This car had lots of quality control issues before it was delivered, according to factory records.” He also has a photo taken the day the first owner took delivery.

Paul may be the latest to use the Avanti sparingly; however, that doesn’t mean it’s not enjoyed while going to, at, and from regional events. Among the Avanti’s honors is an AACA First Place in 2014, HVA Preservation First in Class at the St. Michaels Concours d’Elegance in 2014, Preservation First in Class at the Pinehurst Concours in 2015, and a Preservation First in Class at the Boca Raton Concours in 2017. No doubt, others find the Avanti to be an automotive treasure, too.

The post This all-original 1963 Studebaker Avanti has enjoyed a charmed life appeared first on The Online Automotive Marketplace.