The one-and-only known Black-owned American automaker

None ventured to undertake what C.R. Patterson & Sons did, making them an industry pioneer in the early days of the automobile.

It is a carmaker with a fate similar to that of many small-time, small-town firms. However, C.R. Patterson & Sons’ tale is all the more amazing as it flourished for 74 years over three generations despite changes in business strategy during a period of technical development and immeasurable racial discrimination.

It was an era when President Woodrow Wilson segregated federal toilets in the U.S. Treasury and the Interior Department. It was an era when D.W. Griffith’s movie glorifying the Klu Klux Klan, “Birth of a Nation,” was considered suitable entertainment. It was an era when sports fans couldn’t accept the first Black heavyweight champion of the world, Jack Johnson, so they searched for “The Great White Hope,” aka a white fighter who could defeat him.

Given the inherent prejudice of the time, it's amazing that there was even one Black-owned automaker. But there was. Its name: C.R. Patterson & Sons, manufacturer of the 1914-17 Patterson-Greenfield.

Unexpected success from an improbable start

Like most early automakers, the Patterson-Greenfield’s story starts decades before, in 1850. That’s when Charles Richard Patterson, or C.R., arrived in Greenfield, Ohio, a town with abolitionist leanings and a stop on the Underground Railroad. C.R. was born a slave in Virginia in 1833.

Once in Greenfield, Patterson worked as a blacksmith at local carriagemaker Dines & Simpson. It was a sign of the town’s temperament when he became a shop foreman, working among and supervising an integrated workforce. He married in 1864 and had six children. By 1873, Patterson’s reputation led J.P. Lowe, a white man, to finance and front Patterson as a partner in his new carriage business, J.P. Lowe and Company. By 1888, the company employed 10, according to Ohio’s Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But the Panic of 1893 ignited a four-year depression that decimated many banks and businesses, including J.P. Lowe and Company. J.P. wanted out, and C.R. obliged, becoming the sole proprietor of the renamed C.R. Patterson & Sons. By 1900, an integrated workforce of 50 constructed 28 different horse-drawn carriage styles priced from $120 to $150, including commercial vehicles.

C.R. Patterson & Sons took advantage of changing times

In 1910, C.R. died, and his son Frederick took his place atop the company. It was a time when car ownership was exploding thanks to Henry Ford’s Model T. The year before, there was one car for every 65,000 people. Now, there was one for every 800 people, and automobile servicing had become a side business for Patterson. The company had considered building cars as early as 1902, but it was C.R.’s company at the time, and he was not interested in such a venture.

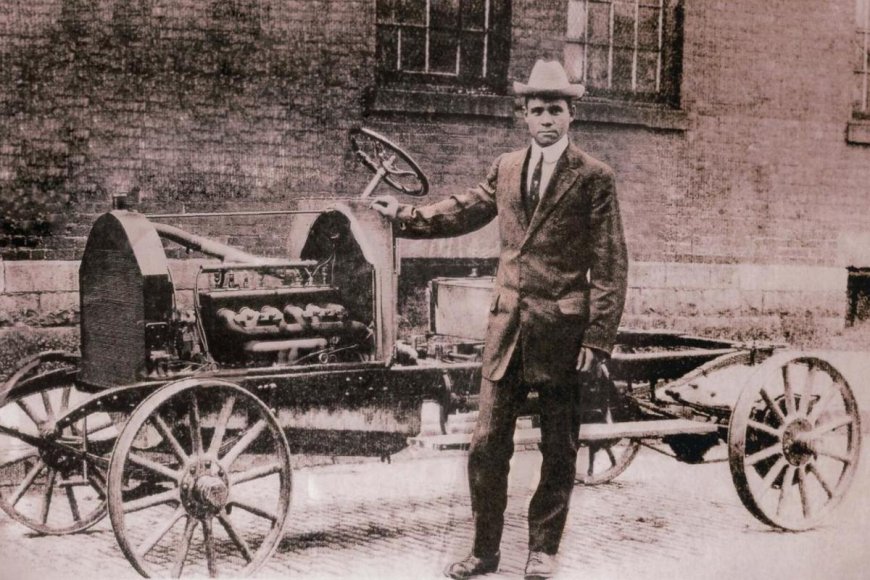

Now, with his son in charge, the company would take the plunge into the new horseless carriage business. Automotive Hall of Fame

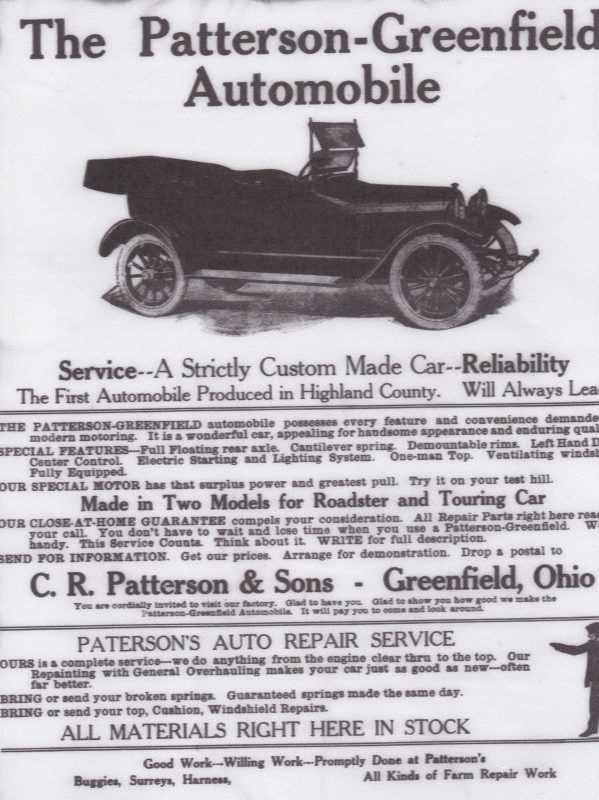

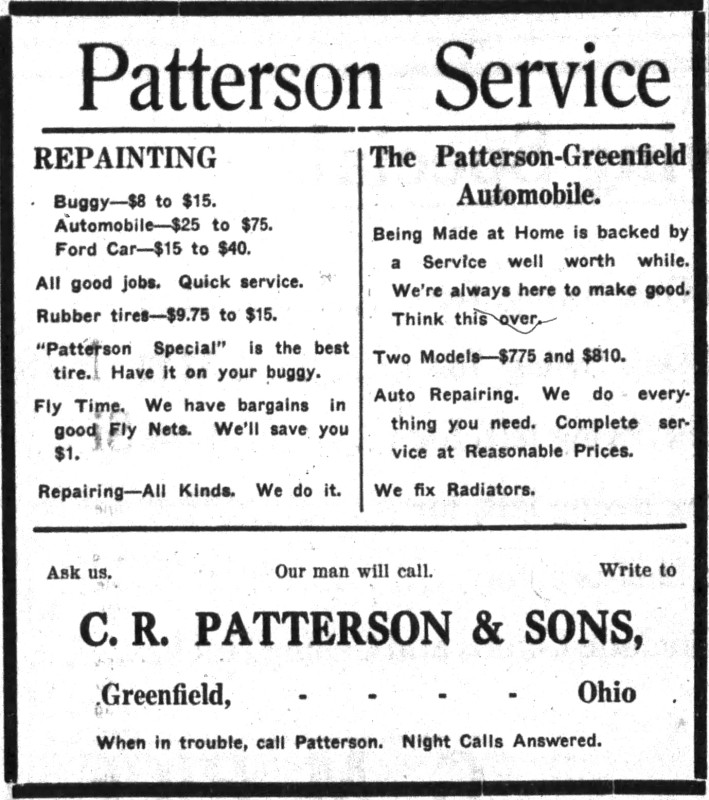

The resulting car, the Patterson-Greenfield, used off-the-shelf parts like many smaller automakers of the time. They bought the steel frame, cantilever springs, rear axle, demountable rims, electric starter, electric lighting, and a ventilated windshield.

Power came from Golden, Belknap, & Swartz, a Detroit-based engine manufacturer that operated from 1910 through 1924. Rated at 22.5 horsepower, the Patterson-Greenfield’s L-head four-cylinder had more power than a Model T and used a conventional three-speed manual transmission rather than a planetary unit. Offered as a closed touring car or open roadster, prices ranged from $685 to $850, or $21,200 to $26,305 adjusted for inflation.

Sold using the advertising tagline, “the only Negro Automobile Manufacturing Concern in the United States,” by 1917, 150 cars were built before production ended.

But it was too little, too late

It all came down to timing.

Patterson could have built his first car in 1902, like fellow carriagemaker Studebaker. That was one year before Ford Motor Company was founded and six years before GM was established. With the industry in its infancy, it might have been a success, but by 1917, Patterson couldn’t compete against such mass producers. The onset of World War I, the increasing costs of raw materials, and the fact that the company was Black-owned prevented them from obtaining the financing needed to expand.

As a result, Patterson changed its business strategy, tapping into its long-held skill: coachbuilding. The company began producing custom bodies for commercial vehicles as the Greenfield Bus Body Company. Patterson supplied school bus bodies to Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky, transit buses in Cincinnati and Cleveland, as well as insulated cargo trucks, hearses, moving vans, ice, bakery, and milk trucks on Chevrolet, Dodge, Ford, Graham, Reo, and International chassis. Frederick’s son, Frederick Jr., guided their design. Automotive Hall of Fame

The company thrived until Frederick's death in 1932, and new school bus safety standards in 1935 stained its ability to compete. A misguided move to Gallipolis, Ohio, proved fatal, and in 1939, the company closed for good. None of its vehicles or the buildings in which they were built survived.

Final thoughts

Yet C.R. Patterson & Sons’ history is a remarkable one. That the one-and-only known Black-owned automaker, founded by a former slave, found success in an overwhelmingly malicious culture for three generations is quite an accomplishment, one that led to Charles Richard Patterson and Frederick Patterson being inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 2021.